Closing the Sub-Seasonal Weather Prediction Gap

From NOAA

Predicting the weather a few days in advance is a complex undertaking. But what about the weather 3 to 4 weeks from now? Producing that kind of forecast is a daunting challenge — but is crucial for a slew of communities. These future forecasts, called sub-seasonal predictions, can help energy companies determine how much power to produce to meet demands for upcoming months; they assist water resource managers controlling reservoir levels ahead of upcoming water use; they even help farmers understand which crops to plant in the face of potential dry weather.

https://twitter.com/NWSCPC/status/962060300378763264Thanks to a team of scientists led by Nat Johnson, an Associate Research Scholar at NOAA’s Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory (GFDL) and the Cooperative Institute for Climate Science at Princeton University, NOAA’s forecasters at the Climate Prediction Center (CPC) are increasing the accuracy of their forecast outlooks for multiple weeks into the future. They now have a tool that provides week 3-4 guidance for precipitation, and even better guidance for temperature — all while helping them understand what drives the weather we see several weeks from now.

“The guidance supplied by this tool will allow CPC forecasters to refine and increase the confidence in their forecasts, and even reduce the time to generate their forecasts,” said Johnson. “It also provides the expected temperature and precipitation impacts, and helps us as forecasters understand the drivers behind a forecast.”

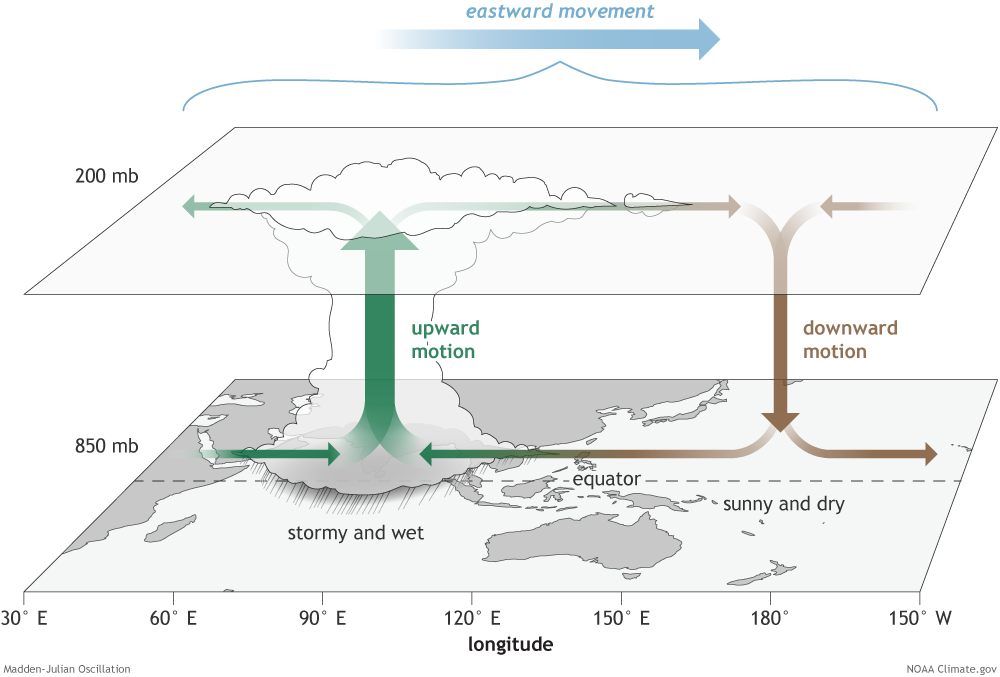

[The surface and upper-atmosphere structure of the MJO for a period when enhanced convection (thunderstorm cloud) is centered over the Indian Ocean and suppressed convection is centered over the west-central Pacific Ocean. The MJO travels eastward over time, eventually circling the globe and returning to its point of origin. Credit: NOAA drawing by Fiona Martin.]

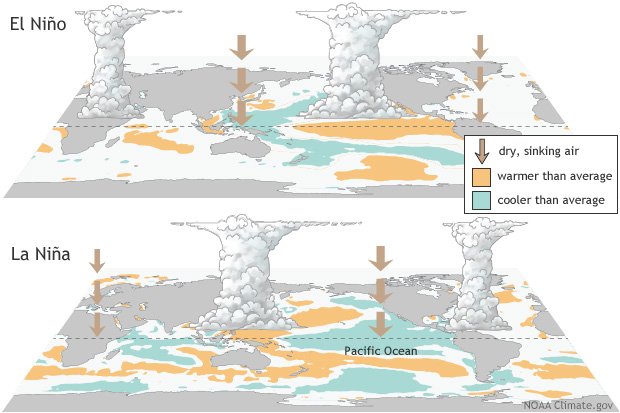

Johnson’s tool was tested for operations as part of a NOAA MAPP ProgramClimate Test Bed project during the experimental phase of CPC’s week 3-4 temperature and precipitation outlook maps. Unlike the guidance CPC heavily relies on from dynamical models, which use equations that model the dynamics of the ocean and atmosphere, Johnson’s new tool provides guidance using statistical models. These probability-heavy models produce predictions based on a long history of past atmospheric observations, and of patterns that influence forecasts. Johnson’s team applied long-term climate trends and the initial state of two large-scale patterns in the tropics—the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO)and the Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO)—to better predict week 3-4 temperature and precipitation.

“I consider the project a great success story,” said Dave DeWitt, CPC Director, regarding the new tool. DeWitt formally declared the tool operational, during a recent post-project review.

[El Niño and La Niña are the warm and cool phases of a recurring climate pattern across the tropical Pacific —the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, or “ENSO” for short. The pattern can shift back and forth irregularly every two to seven years, and each phase triggers predictable disruptions of temperature, precipitation, and winds. These changes disrupt the large-scale air movements in the tropics, triggering a cascade of global side effects. Credit: NOAA]

Beyond the tool’s operational success, Johnson believes that his MAPP Program-Climate Test Bed project demonstrates the importance of a partnership between university and federal scientists for transferring the latest scientific research into a tool that promotes NOAA’s mission.

“NOAA provided a means of translating the accumulation of scientific knowledge into a practical form that benefits a wide range of users,” Johnson stated. “Now communities in need of these forecasts can be confident that the CPC is offering week 3-4 outlooks rooted in guidance, with a track record of reliability.”

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace Michaels