How Lightning Sensors on a Weather Satellites Track Meteoroids

Special Stories

20 Jul 2018 8:41 AM

[A large meteor bolts across the sky in Southern Australia on April 24, 2011. (CC via NOAA)]

From NOAA

What do lightning strikes and meteoroids zipping through space have in common? It turns out they both can be tracked from a weather satellite. Scientists have discovered that the Geostationary Lightning Mapper on NOAA’s GOES-16 and GOES-17 satellites sees more than just lightning flashes in our skies.

Meteoroids routinely bombard Earth's atmosphere from outer space. These small rock fragments, which come from comets or asteroids orbiting the sun, hurtle through space at speeds reaching 100,000 mph or more. When they enter our atmosphere as meteors, their resistance with the surrounding air creates intense heat, which in most cases vaporizes them to dust long before they reach the ground.

The brightest meteors, called bolides, make quite a flash when they explode in the Earth’s atmosphere. Commonly known as fireballs, these large meteoroids can measure several feet in diameter and appear as bright, or sometimes even brighter, than the full moon. While several thousand large meteors enter (and burn up in) Earth’s atmosphere each day, the vast majority of them occur over the oceans and uninhabited regions, leaving them undetected.

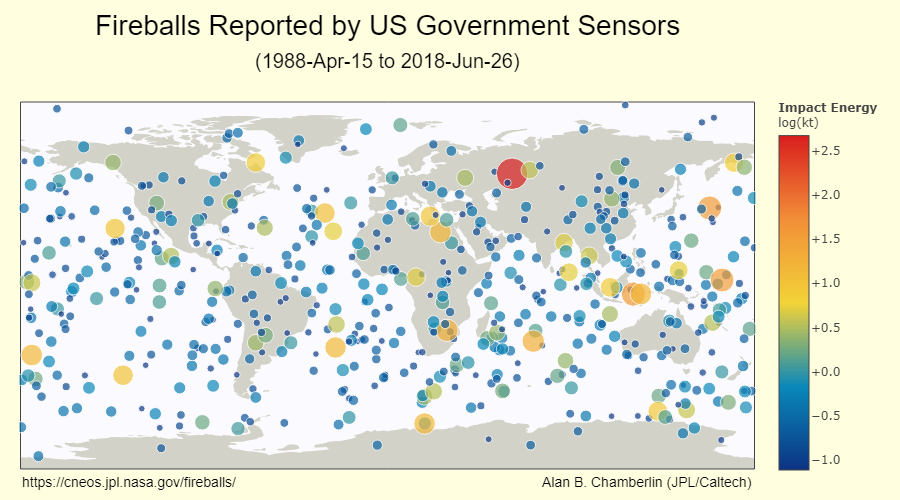

[Recorded incidents of fireballs around the world, 1988-2018. Brighter colors denote larger impacts. (Credit: NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory)]

Until recently, tracking bolides has largely been the work of U.S. military satellites in geostationary orbit. Now, however, an instrument on-board NOAA’s two newest geostationary weather satellites (GOES-16 and GOES-17) designed to detect a different type of flash – lightning – has also observed these spectacularly bright meteors flying through our atmosphere.

In 2017, the Geostationary Lightning Mapper on-board NOAA’s GOES East (GOES-16) satellite, detected several bolides throughout the Western Hemisphere. The observations occurred during the satellite’s post-launch test phase and were reported in a newly published paper online this week.

The brightest and most energetic meteor occurred over the western Atlantic Ocean on March 11, about 300 miles southeast of Bermuda. Data from other U.S. government satellites showed the resulting explosion in Earth’s atmosphere could be traced to an asteroid about 6 to 9 feet in diameter, an event that happens only about once per year around the entire globe.

[Recorded incidents of fireballs around the world, 1988-2018. Brighter colors denote larger impacts. (Credit: NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory)]

Until recently, tracking bolides has largely been the work of U.S. military satellites in geostationary orbit. Now, however, an instrument on-board NOAA’s two newest geostationary weather satellites (GOES-16 and GOES-17) designed to detect a different type of flash – lightning – has also observed these spectacularly bright meteors flying through our atmosphere.

In 2017, the Geostationary Lightning Mapper on-board NOAA’s GOES East (GOES-16) satellite, detected several bolides throughout the Western Hemisphere. The observations occurred during the satellite’s post-launch test phase and were reported in a newly published paper online this week.

The brightest and most energetic meteor occurred over the western Atlantic Ocean on March 11, about 300 miles southeast of Bermuda. Data from other U.S. government satellites showed the resulting explosion in Earth’s atmosphere could be traced to an asteroid about 6 to 9 feet in diameter, an event that happens only about once per year around the entire globe.

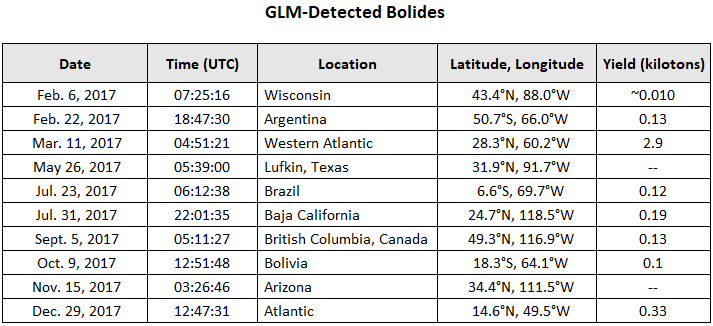

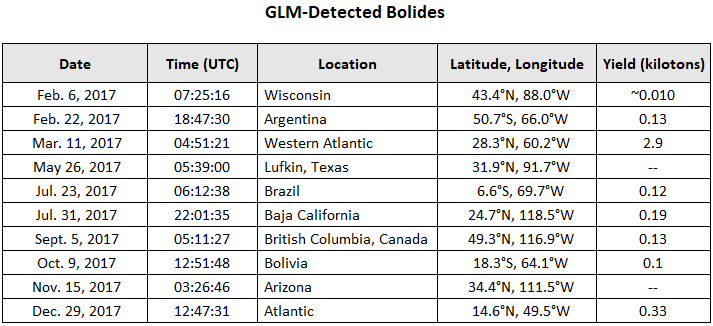

[Date, time and location of the ten bolides studied by Jenniskens et al. (2018). The 'yield' column shows the impact energy of each meteor, measured in kilotons of TNT.]

The Geostationary Lightning Mapper (GLM) also tracked several smaller bolides in other parts of North and South America, from western Canada to southern Argentina. One of these even left behind tangible evidence: Two months after the GLM detected a bolide in British Columbia, Canada, researchers confirmed that they had discovered several meteorites, the name given to fragments of meteoroids that survive their journey through the Earth’s atmosphere and land on the ground.

While designed for mapping lightning flashes, the Geostationary Lightning Mapper can observe large meteors anywhere throughout its coverage area. The instrument takes 500 images of Earth every second, allowing it to measure the shape of a meteor “light curve,” or the change in brightness of a meteor with time, with millisecond precision. In order for the GLM to detect these flashes, the bolides need an apparent visual magnitude of minus 14 at night, which is slightly brighter than the full moon.

Unlike most individual lightning flashes, which are shorter than a millisecond, the light signature of bolides lasts slightly longer. The flash is similar to what the GLM sees in lightning with continuing current, in which the cloud continues to glow (for tens of milliseconds) while lightning transfers charge to the ground. To make sure that the flashes were from large meteors, and not lightning, researchers checked that the GLM’s sensors had registered the flashes as “non-lightning” events.

[Date, time and location of the ten bolides studied by Jenniskens et al. (2018). The 'yield' column shows the impact energy of each meteor, measured in kilotons of TNT.]

The Geostationary Lightning Mapper (GLM) also tracked several smaller bolides in other parts of North and South America, from western Canada to southern Argentina. One of these even left behind tangible evidence: Two months after the GLM detected a bolide in British Columbia, Canada, researchers confirmed that they had discovered several meteorites, the name given to fragments of meteoroids that survive their journey through the Earth’s atmosphere and land on the ground.

While designed for mapping lightning flashes, the Geostationary Lightning Mapper can observe large meteors anywhere throughout its coverage area. The instrument takes 500 images of Earth every second, allowing it to measure the shape of a meteor “light curve,” or the change in brightness of a meteor with time, with millisecond precision. In order for the GLM to detect these flashes, the bolides need an apparent visual magnitude of minus 14 at night, which is slightly brighter than the full moon.

Unlike most individual lightning flashes, which are shorter than a millisecond, the light signature of bolides lasts slightly longer. The flash is similar to what the GLM sees in lightning with continuing current, in which the cloud continues to glow (for tens of milliseconds) while lightning transfers charge to the ground. To make sure that the flashes were from large meteors, and not lightning, researchers checked that the GLM’s sensors had registered the flashes as “non-lightning” events.

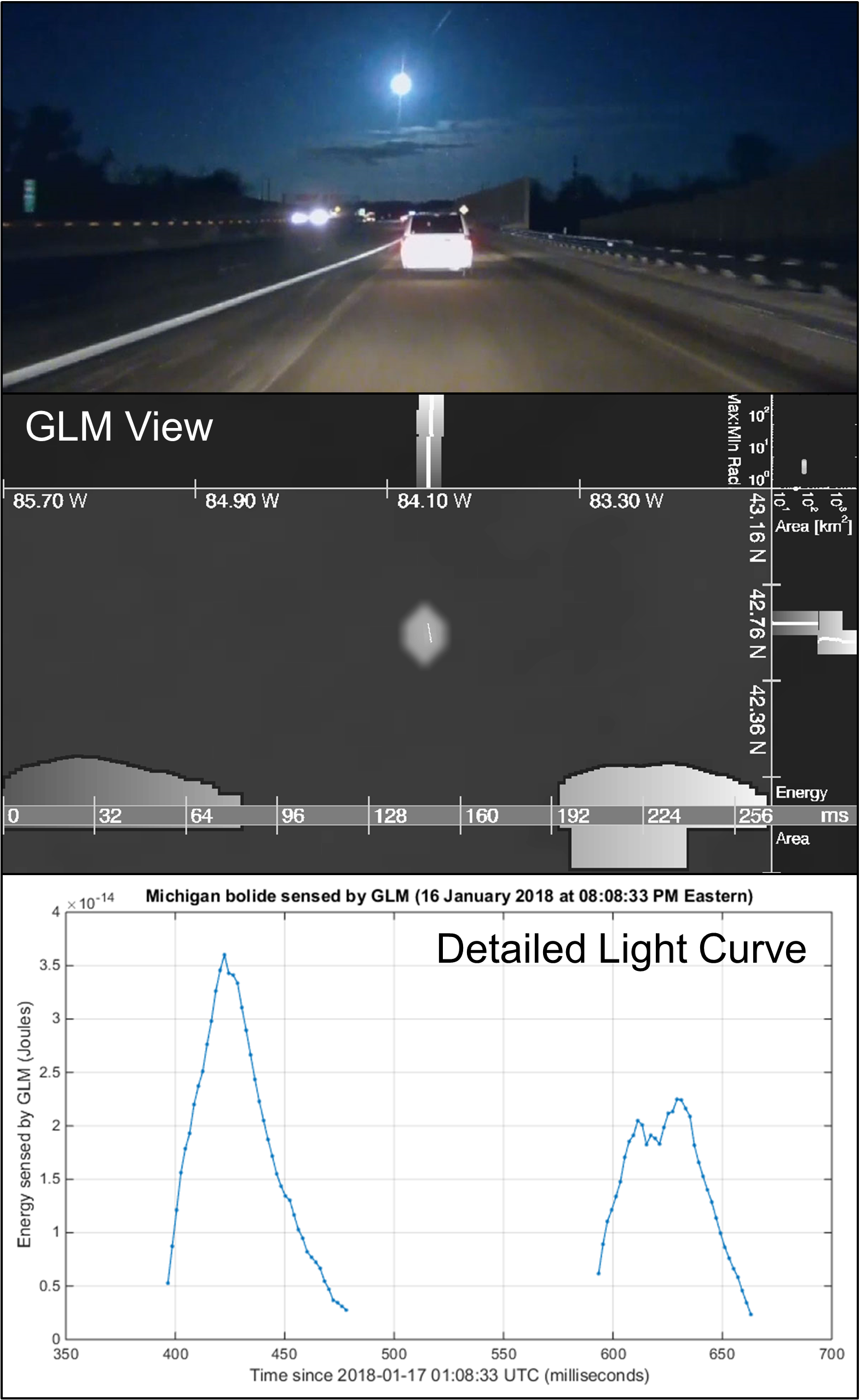

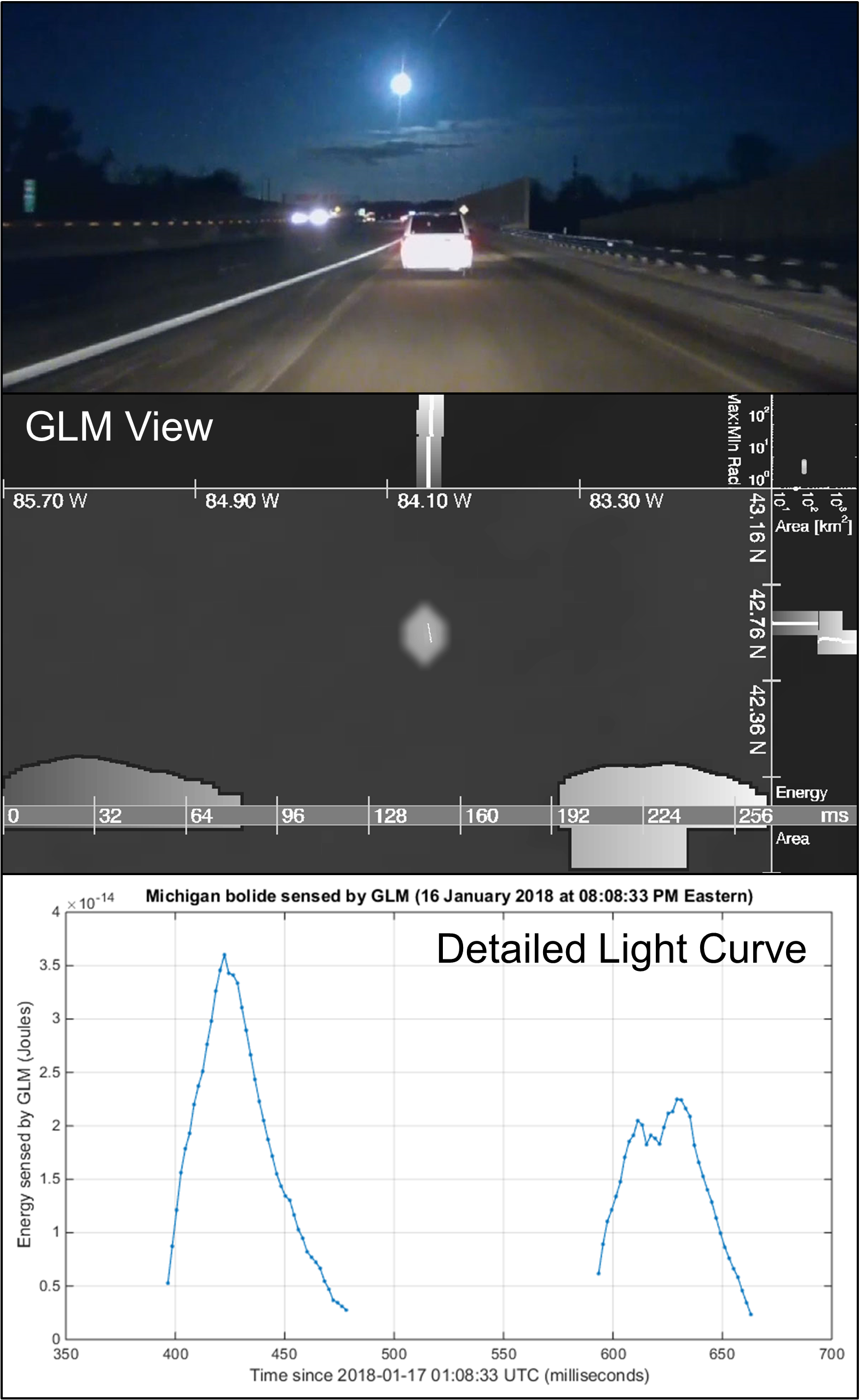

[On Jan. 16, 2018, the GLM detected a large meteor south of Howell, Michigan (near Detroit). The plot shows the energy and light sensed from the GLM as the bolide crossed the sky. (Credit: NOAA/University of Maryland)]

Does this mean the lightning mapper can also capture the dazzling streaks of a meteor shower we occasionally see over our own backyard? Not exactly. Meteor showers occur when thousands of tiny rocks and dust fragments from space zip across the sky at the same time. These events are usually fainter than minus 13 visual magnitude, however, which means they aren’t bright enough to be detected by the GLM.

Of course, the number of bolides pale in comparison to the millions of lightning flashes that occur across Earth each year. That means the GLM’s main job will be to monitor lightning activity and help us forecast severe thunderstorms. Nonetheless, the GLM’s ability to detect meteoroids means that NOAA weather satellites may eventually provide an open source of information about how and when these small asteroids from outer space impact the Earth’s atmosphere.

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace Michaels

[On Jan. 16, 2018, the GLM detected a large meteor south of Howell, Michigan (near Detroit). The plot shows the energy and light sensed from the GLM as the bolide crossed the sky. (Credit: NOAA/University of Maryland)]

Does this mean the lightning mapper can also capture the dazzling streaks of a meteor shower we occasionally see over our own backyard? Not exactly. Meteor showers occur when thousands of tiny rocks and dust fragments from space zip across the sky at the same time. These events are usually fainter than minus 13 visual magnitude, however, which means they aren’t bright enough to be detected by the GLM.

Of course, the number of bolides pale in comparison to the millions of lightning flashes that occur across Earth each year. That means the GLM’s main job will be to monitor lightning activity and help us forecast severe thunderstorms. Nonetheless, the GLM’s ability to detect meteoroids means that NOAA weather satellites may eventually provide an open source of information about how and when these small asteroids from outer space impact the Earth’s atmosphere.

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace Michaels

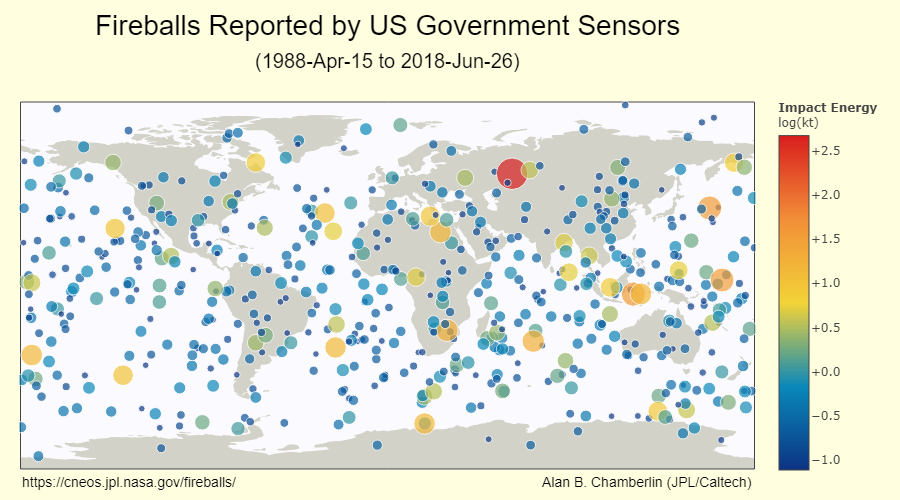

[Recorded incidents of fireballs around the world, 1988-2018. Brighter colors denote larger impacts. (Credit: NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory)]

Until recently, tracking bolides has largely been the work of U.S. military satellites in geostationary orbit. Now, however, an instrument on-board NOAA’s two newest geostationary weather satellites (GOES-16 and GOES-17) designed to detect a different type of flash – lightning – has also observed these spectacularly bright meteors flying through our atmosphere.

In 2017, the Geostationary Lightning Mapper on-board NOAA’s GOES East (GOES-16) satellite, detected several bolides throughout the Western Hemisphere. The observations occurred during the satellite’s post-launch test phase and were reported in a newly published paper online this week.

The brightest and most energetic meteor occurred over the western Atlantic Ocean on March 11, about 300 miles southeast of Bermuda. Data from other U.S. government satellites showed the resulting explosion in Earth’s atmosphere could be traced to an asteroid about 6 to 9 feet in diameter, an event that happens only about once per year around the entire globe.

[Recorded incidents of fireballs around the world, 1988-2018. Brighter colors denote larger impacts. (Credit: NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory)]

Until recently, tracking bolides has largely been the work of U.S. military satellites in geostationary orbit. Now, however, an instrument on-board NOAA’s two newest geostationary weather satellites (GOES-16 and GOES-17) designed to detect a different type of flash – lightning – has also observed these spectacularly bright meteors flying through our atmosphere.

In 2017, the Geostationary Lightning Mapper on-board NOAA’s GOES East (GOES-16) satellite, detected several bolides throughout the Western Hemisphere. The observations occurred during the satellite’s post-launch test phase and were reported in a newly published paper online this week.

The brightest and most energetic meteor occurred over the western Atlantic Ocean on March 11, about 300 miles southeast of Bermuda. Data from other U.S. government satellites showed the resulting explosion in Earth’s atmosphere could be traced to an asteroid about 6 to 9 feet in diameter, an event that happens only about once per year around the entire globe.

[Date, time and location of the ten bolides studied by Jenniskens et al. (2018). The 'yield' column shows the impact energy of each meteor, measured in kilotons of TNT.]

The Geostationary Lightning Mapper (GLM) also tracked several smaller bolides in other parts of North and South America, from western Canada to southern Argentina. One of these even left behind tangible evidence: Two months after the GLM detected a bolide in British Columbia, Canada, researchers confirmed that they had discovered several meteorites, the name given to fragments of meteoroids that survive their journey through the Earth’s atmosphere and land on the ground.

While designed for mapping lightning flashes, the Geostationary Lightning Mapper can observe large meteors anywhere throughout its coverage area. The instrument takes 500 images of Earth every second, allowing it to measure the shape of a meteor “light curve,” or the change in brightness of a meteor with time, with millisecond precision. In order for the GLM to detect these flashes, the bolides need an apparent visual magnitude of minus 14 at night, which is slightly brighter than the full moon.

Unlike most individual lightning flashes, which are shorter than a millisecond, the light signature of bolides lasts slightly longer. The flash is similar to what the GLM sees in lightning with continuing current, in which the cloud continues to glow (for tens of milliseconds) while lightning transfers charge to the ground. To make sure that the flashes were from large meteors, and not lightning, researchers checked that the GLM’s sensors had registered the flashes as “non-lightning” events.

[Date, time and location of the ten bolides studied by Jenniskens et al. (2018). The 'yield' column shows the impact energy of each meteor, measured in kilotons of TNT.]

The Geostationary Lightning Mapper (GLM) also tracked several smaller bolides in other parts of North and South America, from western Canada to southern Argentina. One of these even left behind tangible evidence: Two months after the GLM detected a bolide in British Columbia, Canada, researchers confirmed that they had discovered several meteorites, the name given to fragments of meteoroids that survive their journey through the Earth’s atmosphere and land on the ground.

While designed for mapping lightning flashes, the Geostationary Lightning Mapper can observe large meteors anywhere throughout its coverage area. The instrument takes 500 images of Earth every second, allowing it to measure the shape of a meteor “light curve,” or the change in brightness of a meteor with time, with millisecond precision. In order for the GLM to detect these flashes, the bolides need an apparent visual magnitude of minus 14 at night, which is slightly brighter than the full moon.

Unlike most individual lightning flashes, which are shorter than a millisecond, the light signature of bolides lasts slightly longer. The flash is similar to what the GLM sees in lightning with continuing current, in which the cloud continues to glow (for tens of milliseconds) while lightning transfers charge to the ground. To make sure that the flashes were from large meteors, and not lightning, researchers checked that the GLM’s sensors had registered the flashes as “non-lightning” events.

[On Jan. 16, 2018, the GLM detected a large meteor south of Howell, Michigan (near Detroit). The plot shows the energy and light sensed from the GLM as the bolide crossed the sky. (Credit: NOAA/University of Maryland)]

Does this mean the lightning mapper can also capture the dazzling streaks of a meteor shower we occasionally see over our own backyard? Not exactly. Meteor showers occur when thousands of tiny rocks and dust fragments from space zip across the sky at the same time. These events are usually fainter than minus 13 visual magnitude, however, which means they aren’t bright enough to be detected by the GLM.

Of course, the number of bolides pale in comparison to the millions of lightning flashes that occur across Earth each year. That means the GLM’s main job will be to monitor lightning activity and help us forecast severe thunderstorms. Nonetheless, the GLM’s ability to detect meteoroids means that NOAA weather satellites may eventually provide an open source of information about how and when these small asteroids from outer space impact the Earth’s atmosphere.

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace Michaels

[On Jan. 16, 2018, the GLM detected a large meteor south of Howell, Michigan (near Detroit). The plot shows the energy and light sensed from the GLM as the bolide crossed the sky. (Credit: NOAA/University of Maryland)]

Does this mean the lightning mapper can also capture the dazzling streaks of a meteor shower we occasionally see over our own backyard? Not exactly. Meteor showers occur when thousands of tiny rocks and dust fragments from space zip across the sky at the same time. These events are usually fainter than minus 13 visual magnitude, however, which means they aren’t bright enough to be detected by the GLM.

Of course, the number of bolides pale in comparison to the millions of lightning flashes that occur across Earth each year. That means the GLM’s main job will be to monitor lightning activity and help us forecast severe thunderstorms. Nonetheless, the GLM’s ability to detect meteoroids means that NOAA weather satellites may eventually provide an open source of information about how and when these small asteroids from outer space impact the Earth’s atmosphere.

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace MichaelsAll Weather News

More