Study on the Rapid Intensification of Hurricane Michael

Special Stories

5 Nov 2020 4:00 AM

[Hurricane Michael makes landfall at Mexico Beach, Fla. at 1:30 p.m. on Oct 10th, 2018. Credit: NOAA]

[Written from NOAA HRD] Hurricane Michael was the first category 5 storm to hit the U.S. since Hurricane Andrew in 1992, with the third lowest pressure ever recorded for a landfalling storm in the Atlantic Basin. Michael made landfall in the Florida Panhandle near Mexico Beach on October 10th, 2018. A new study, published recently in the American Meteorological Society's Monthly Weather Review, take a closer look at the rapid intensification of the storm.

NOAA Hurricane Hunter aircraft flew multiple missions into Hurricane Michael of 2018. During each mission conducted by the NOAA P-3s, the ocean temperature was sampled all around the storm as part of a special collaboration with the University of Miami. The aircraft also released dropwindsondes that measure temperature, humidity, pressure, and wind four times every second as they fall from the aircraft. Doppler radars on the aircraft measured the wind all around the aircraft as the planes fly through and around the hurricane. This all allowed researchers to look at the hurricane itself, the ocean below, and the environment around the hurricane all at the same time, to see how warm and cool water below Michael impacted its intensity.

The energy for tropical cyclones comes mainly from the warm ocean below them. The warmer the water, the greater the energy, and the easier it is to transfer that energy (heat and moisture) into the air and into the tropical cyclone, allowing the thunderstorms that sustain the cyclone to develop. Cool water (below about 26C/79F) typically limits the tropical cyclone intensity.

Important Conclusions:

The energy for tropical cyclones comes mainly from the warm ocean below them. The warmer the water, the greater the energy, and the easier it is to transfer that energy (heat and moisture) into the air and into the tropical cyclone, allowing the thunderstorms that sustain the cyclone to develop. Cool water (below about 26C/79F) typically limits the tropical cyclone intensity.

Important Conclusions:

Edited for WeatherNation by Mace Michaels

Edited for WeatherNation by Mace Michaels

The energy for tropical cyclones comes mainly from the warm ocean below them. The warmer the water, the greater the energy, and the easier it is to transfer that energy (heat and moisture) into the air and into the tropical cyclone, allowing the thunderstorms that sustain the cyclone to develop. Cool water (below about 26C/79F) typically limits the tropical cyclone intensity.

Important Conclusions:

The energy for tropical cyclones comes mainly from the warm ocean below them. The warmer the water, the greater the energy, and the easier it is to transfer that energy (heat and moisture) into the air and into the tropical cyclone, allowing the thunderstorms that sustain the cyclone to develop. Cool water (below about 26C/79F) typically limits the tropical cyclone intensity.

Important Conclusions:

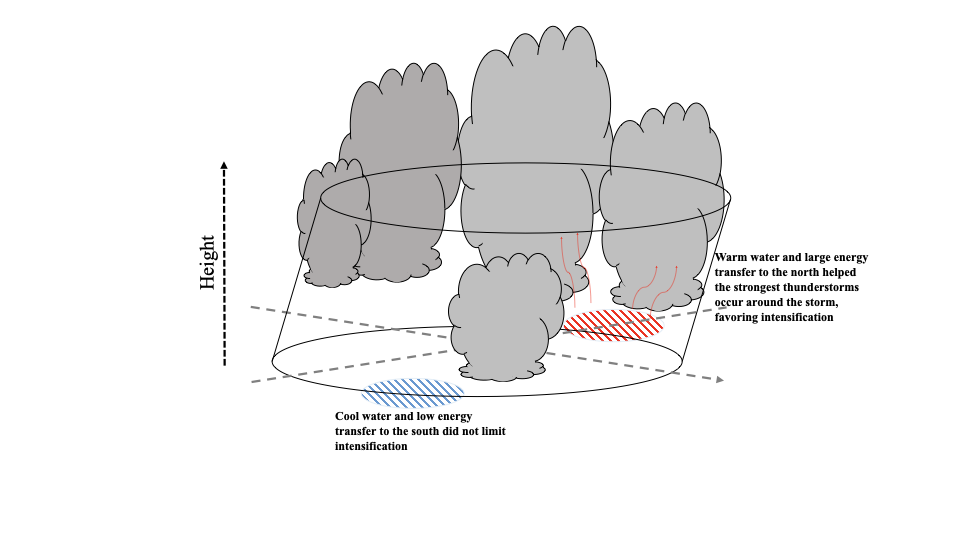

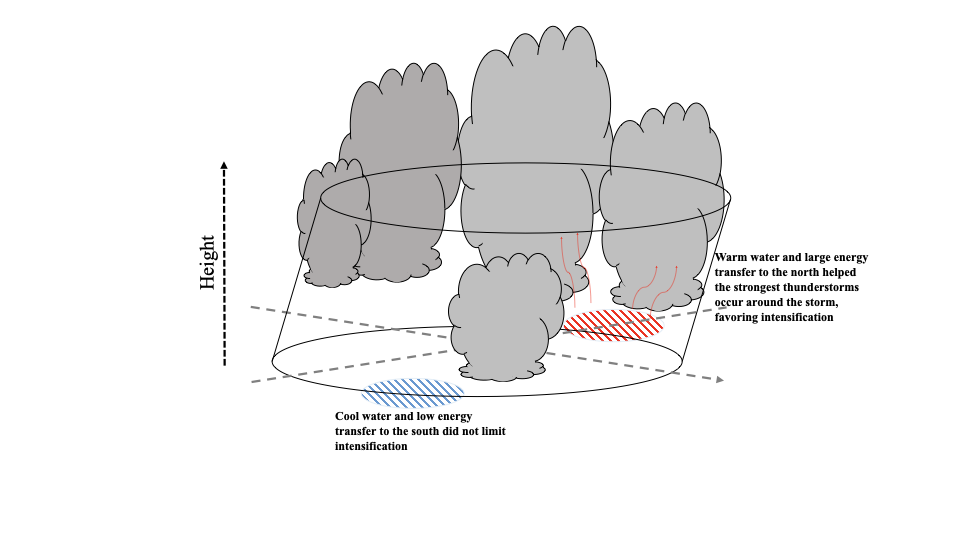

- Cool water is not always detrimental to a hurricane’s intensification. As Michael first developed, the oceanic currents underneath the storm led to areas of cool and warm waters. Even with these fairly cool waters, Michael was able to rapidly intensify.

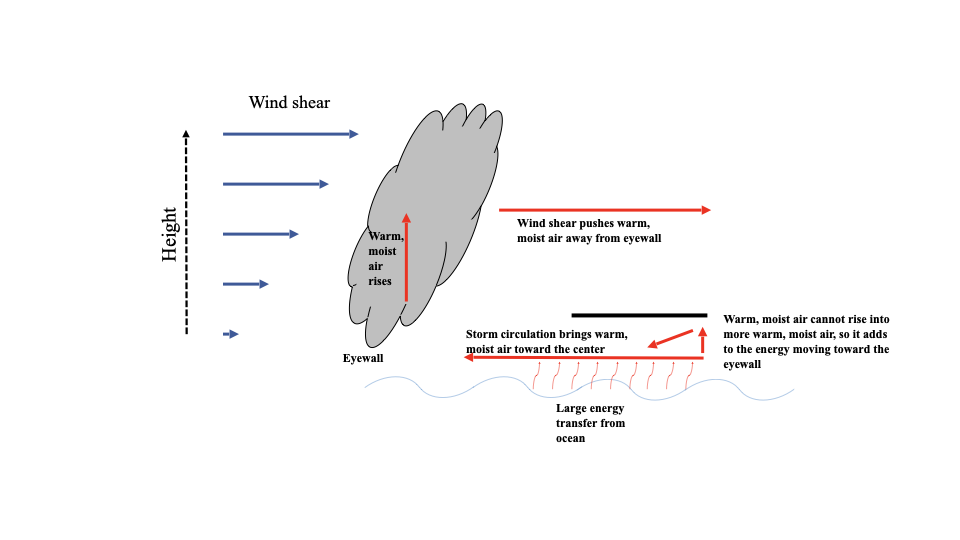

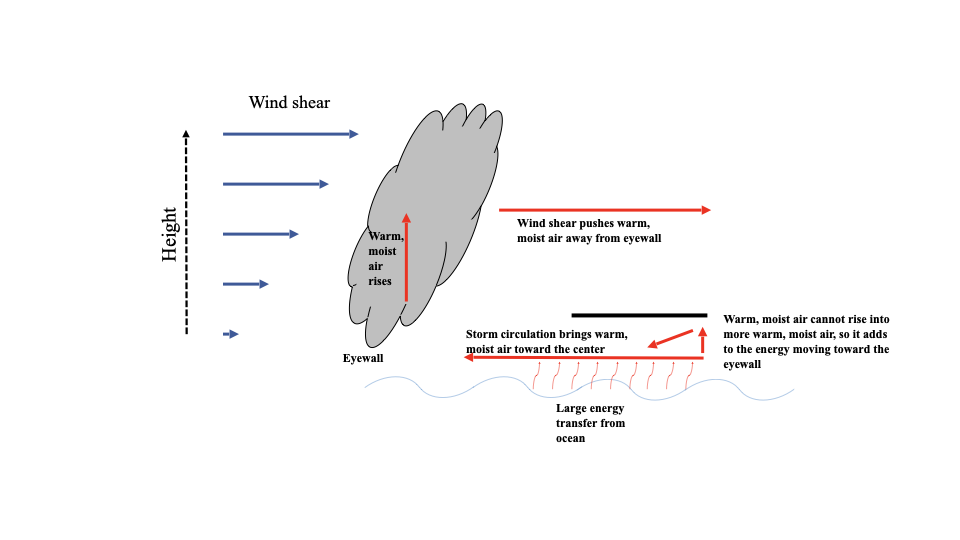

- As Michael approached landfall on the Florida panhandle, the ocean temperature was warm everywhere. This led to more energy transfer from the ocean to the atmosphere. Strong wind in the environment in the middle atmosphere helped push moisture from the eyewall to the outside areas of the storm. The energy from the ocean could not rise into this warm, moist air, so the energy transfer into the center (eyewall) was enhanced. This extra energy transfer made the hurricane more efficient, ultimately helping it intensify up until it reached category-5 intensity at landfall.

- The unique observations used in this study can also be used to improve hurricane forecasts by helping model evaluation and initialization. Observations of both the hurricane and the underlying ocean are critical to understanding intensity change.

Edited for WeatherNation by Mace Michaels

Edited for WeatherNation by Mace MichaelsAll Weather News

More