A Look at Meteotsunamis - Large, Weather-Created Breaking Waves

NOAA scientists determined these waves were part of a meteotsunami, a small, weather-driven tsunami caused by changes in air pressure created by fast-moving severe thunderstorms, tropical storms, squalls or other storm fronts. The waves that hit New Jersey were generated from an intense, offshore squall line known as a derecho and were detected by more than 16 NOAA tide gauges along the East coast.

New research published this month by NOAA finds that, on average, the U.S. East Coast experiences about 25 meteotsunamis per year — though most are less than 1.5 feet high and relatively harmless. Only about one meteotsunami wave a year exceeds 2 feet in height, large enough to cause the injuries and destruction experienced in New Jersey.

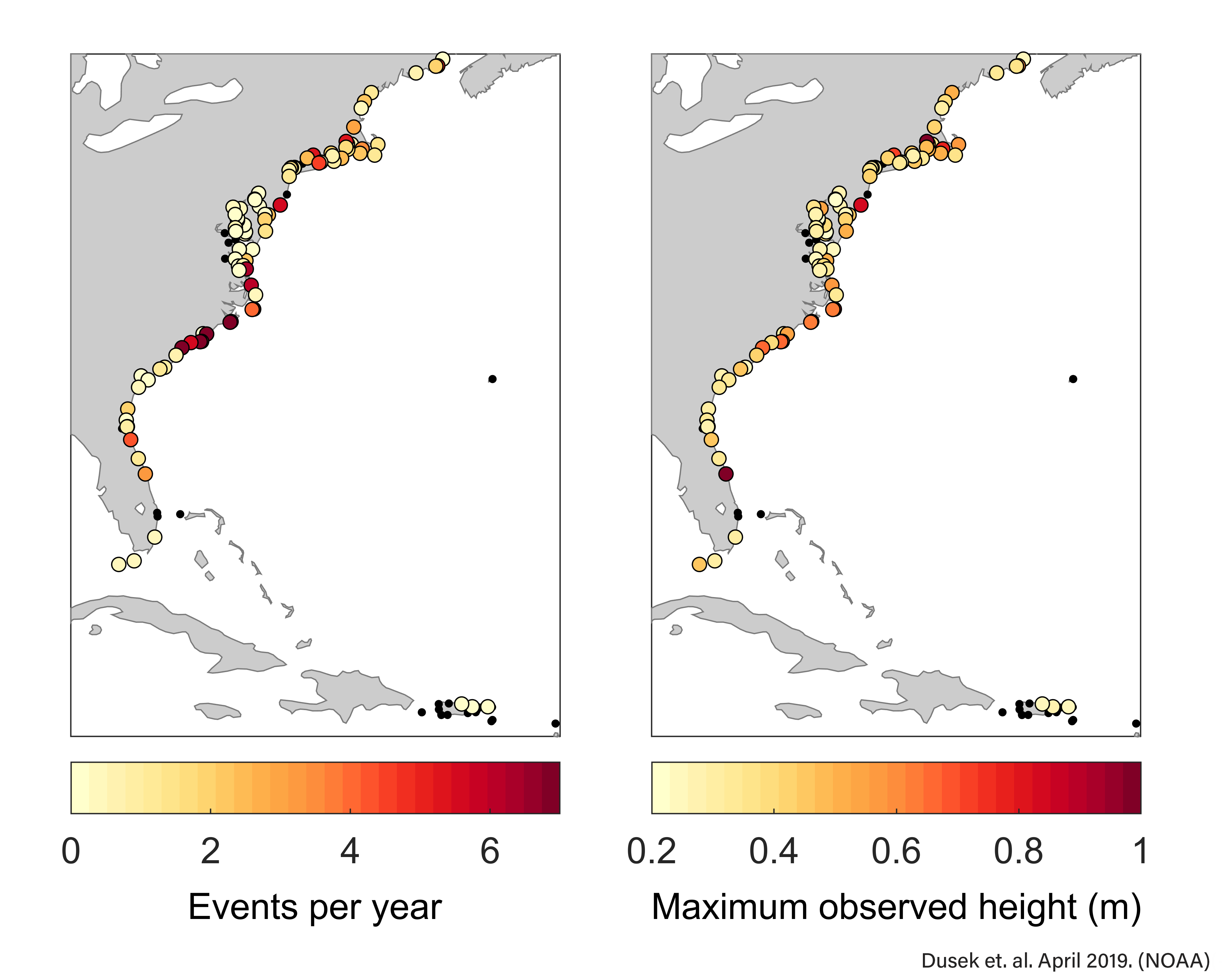

[Where the waves rolled in: NOAA scientists analyzed 22 years (1996-2017) of water level observations at 125 tide gauges along the East coast and found that on average 25 meteostunamis impact the East Coast each year. The figure on the left shows the average number of meteostunami events per year for each location, while the figure on right shows the maximum observed wave height for each meteotsunami event. The most impacted areas are the Carolinas and Long Island Sound. Small black dots indicate no events observed at those locations. (Citation for graphic: Dusek, G., C. DiVeglio, L. Licate, L. Heilman, K. Kirk, C. Paternostro, and A. Miller. 2019: A meteotsunami climatology along the U.S. East Coast. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc. doi:10.1175/BAMS-D-18-0206.1. In press.) (NOAA)]

Small waves that can pack a punch, given the right conditions

Meteotsunamis occur all over the world — including the Great Lakes — but scientists are just beginning to better detect and understand them.

In order to identify the meteotsunamis, which often go unrecorded, study researchers analyzed 22 years (1996-2017) of water level observations from 125 NOAA and partner tide gauges on the East Coast. They found evidence of 548 meteotsunamis, including one that occurred during Hurricane Irma in 2017.

East Coast meteotsunamis happen most often in summer, especially in July — because of thunderstorms — and in the winter due to nor’easters. Research shows that they occur most often in the Carolinas, northern Florida and Long Island Sound, with the largest waves found in areas where estuaries or the shape of the coastline has amplified them.

Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, and Duck, North Carolina, observed the greatest number of events: 148 (7.2 per year) and 130 (6.0 per year), respectively. Wrightsville Beach (8.7 per year) and Cape Hatteras (8.9 per year) in North Carolina had the highest averages per year for any station with at least five years of data.

[Storm clouds loom over Lake Superior. When conditions are right, meteotsunamis may occur in many bodies of water around the world, including the Great Lakes. Some meteotsunamis have been observed to reach heights of 6 feet or more. Meteotsunamis are generally smaller than tsunamis triggered by seismic activity. From NOAA]

More about NOAA meteotsunami science

This study will support ongoing NOAA research to better detect and forecast meteotsunamis to warn the public in near-real time. Other efforts include:

-

NOAA’s Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory are working with partners on developing a real-time meteotsunami warning system in the Great Lakes.

-

The National Weather Service is developing the capability to provide accurate and timely public alerts when meteotsunamis are detected by deep-ocean pressure sensors or coastal high-frequency radars.

-

The National Tsunami Warning Center works hand-in-hand with coastal weather forecast offices to alert people along the coast to potential local threats. NOAA scientists are also helping organize the First World Conference on Meteotsunamis taking place in May 2019.

-

NOAA scientists are also helping organize the First World Conference on Meteotsunamis taking place in May 2019.