A Look Back at March River Flooding that Inundated the Northern Plains

Special Stories

15 Apr 2019 12:09 AM

[March river flooding in Sioux Falls, SD near Cherry Rock Park. Image from the City of Sioux Falls]

[NOAA by Tom Di Liberto] Widespread river flooding wreaked havoc as rivers burst their banks and inundated towns, cities, and farmland across the northern and central Plains in mid-March 2019. The March flooding may just be the first round in a potentially devastating spring flood season across the Plains as rivers are expected to remain elevated as spring temperatures rise and snow melts.

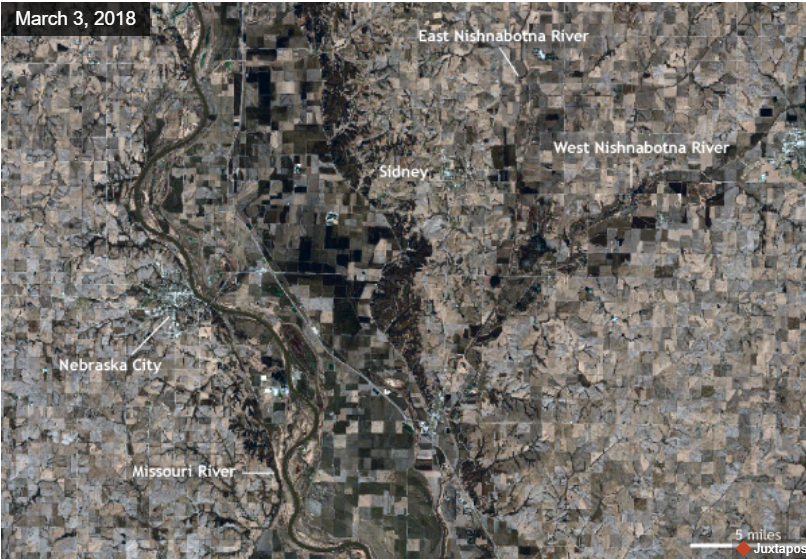

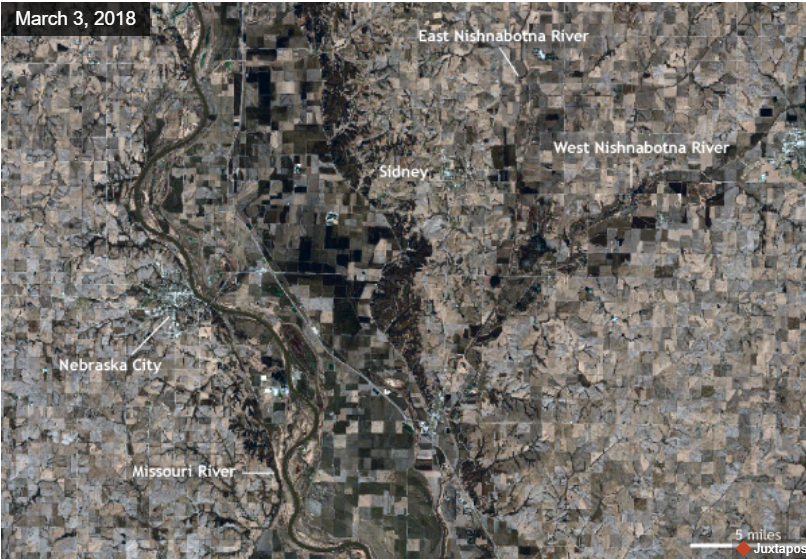

[Comparing the March 2018 (top) and March 2019 (bottom) satellite images of the Missouri River near Nebraska City, Nebraska. A checkerboard of farmland in the center of the 2018 image is submerged by muddy flood waters in 2019 as rain and snowmelt swell the Missouri River to more than five miles across in places. NOAA Climate images, based on Sentinel data from the European Space Agency.]

[Comparing the March 2018 (top) and March 2019 (bottom) satellite images of the Missouri River near Nebraska City, Nebraska. A checkerboard of farmland in the center of the 2018 image is submerged by muddy flood waters in 2019 as rain and snowmelt swell the Missouri River to more than five miles across in places. NOAA Climate images, based on Sentinel data from the European Space Agency.]

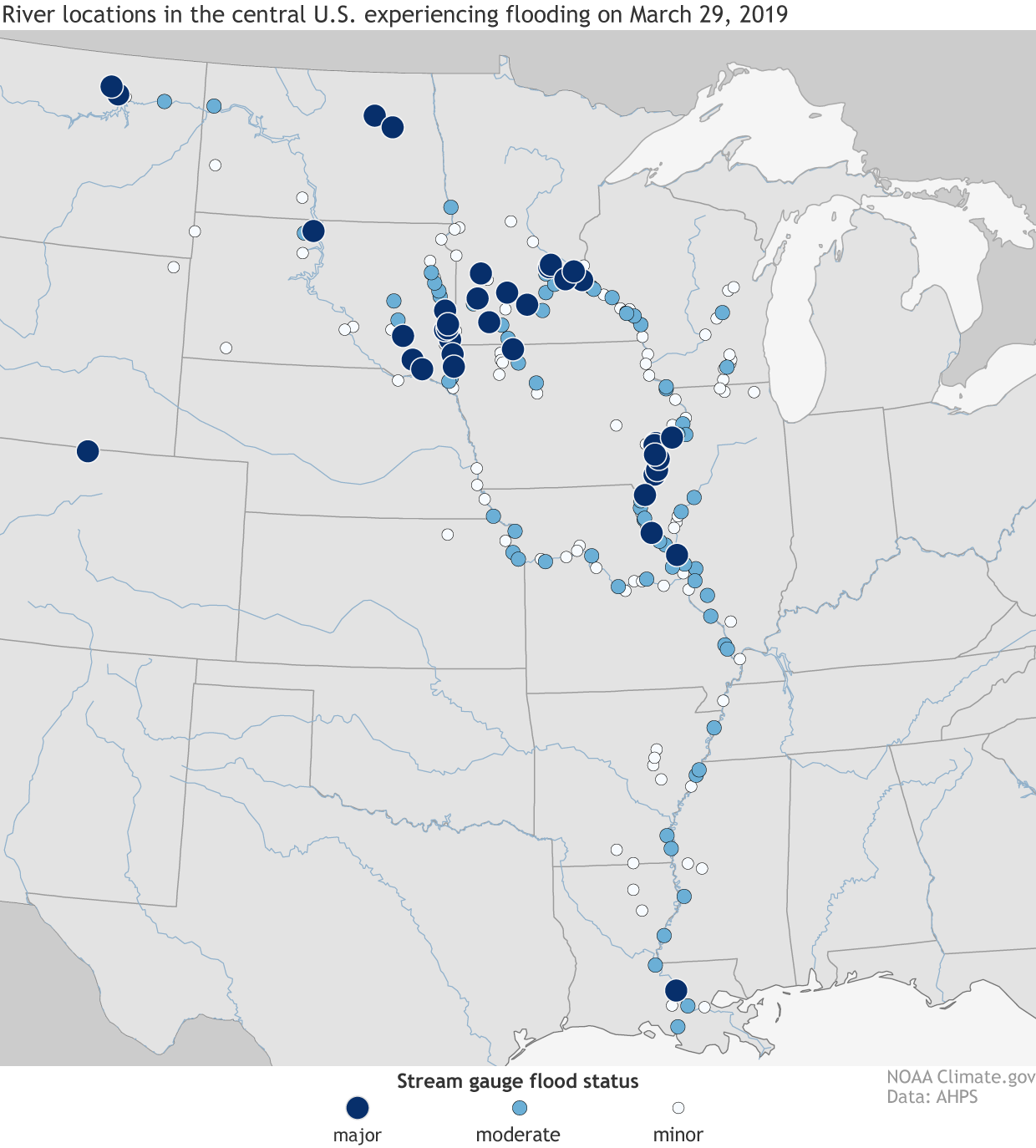

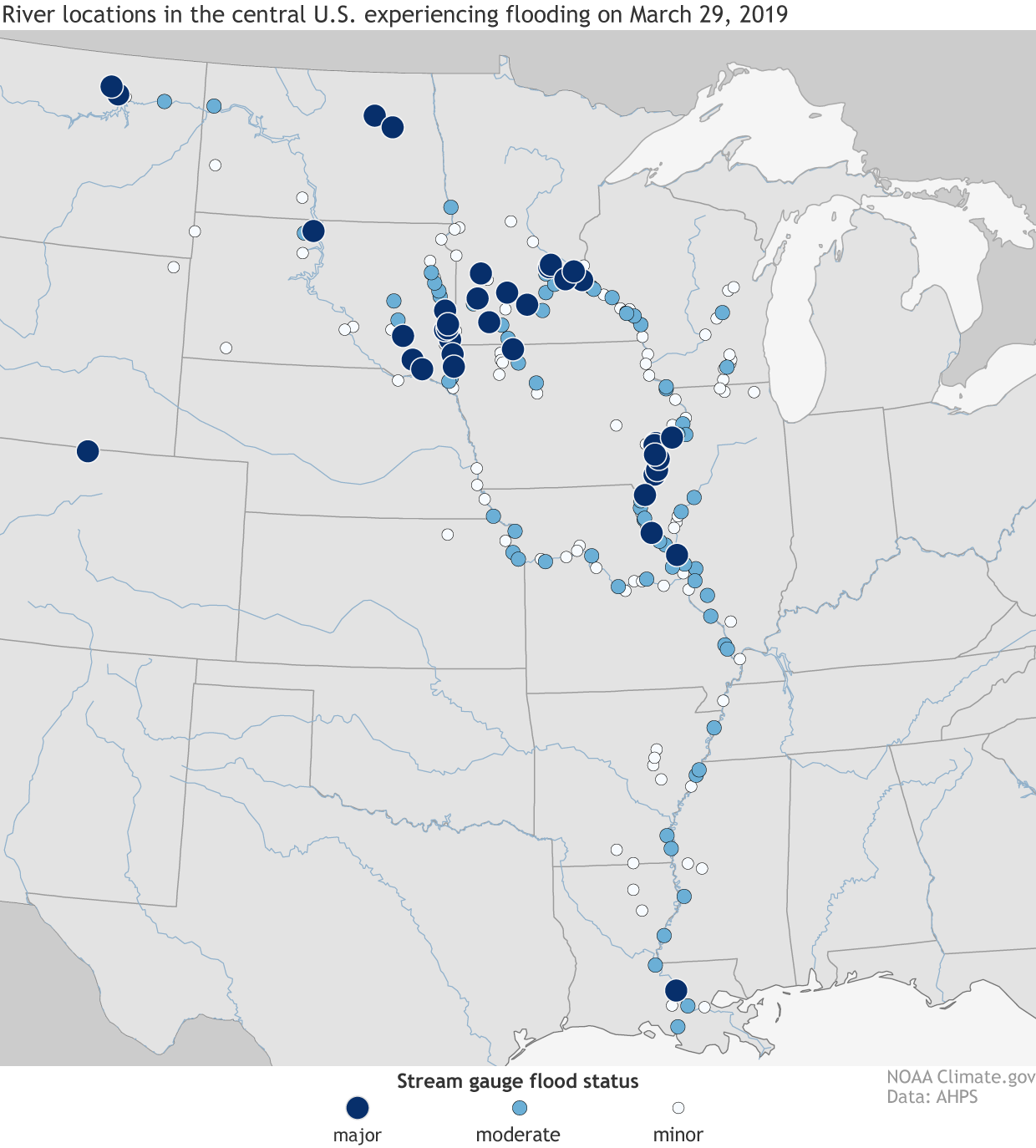

[Flood status for stream gauges across the central United States on March 29, 2019: major (dark blue), moderate (light blue), and minor (white). Numerous stream gauges across many rivers were in major flood status as of the end of March 2019, including gauges along the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers. A rapid melt of snow hastened by a strong spring storm led to a rapid rise in river levels across the Northern and Central Plains. NOAA Climate image, based on data from AHPS.]

The floods completely submerged towns and even lead to the evacuation of the National Weather Service office in Valley, Nebraska, located along the Platte River. Offutt Air Force Base also saw the neighboring river expand its boundaries onto the base, as the Missouri River and Papio Creek inundated southern portions of the base, including runways and about thirty buildings.

The governor of Nebraska, Pete Ricketts, estimated that preliminary and initial damage losses from the flooding in just Nebraska could be more than $1.3 billion with $440 million alone due to crop losses.

Farther north, the floodwaters have left the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota isolated, as waters have washed away roads and left residents stranded for over two weeks.

And even after these floodwaters recede, problems will still be present. As noted in this article in Earther, for farmers, the floodwaters likely have washed away the nutrient-rich topsoil, leaving behind compacted soil, sand, and silt. It will take farmers years to build back soil as productive as what was just washed away into the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers.

[Flood status for stream gauges across the central United States on March 29, 2019: major (dark blue), moderate (light blue), and minor (white). Numerous stream gauges across many rivers were in major flood status as of the end of March 2019, including gauges along the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers. A rapid melt of snow hastened by a strong spring storm led to a rapid rise in river levels across the Northern and Central Plains. NOAA Climate image, based on data from AHPS.]

The floods completely submerged towns and even lead to the evacuation of the National Weather Service office in Valley, Nebraska, located along the Platte River. Offutt Air Force Base also saw the neighboring river expand its boundaries onto the base, as the Missouri River and Papio Creek inundated southern portions of the base, including runways and about thirty buildings.

The governor of Nebraska, Pete Ricketts, estimated that preliminary and initial damage losses from the flooding in just Nebraska could be more than $1.3 billion with $440 million alone due to crop losses.

Farther north, the floodwaters have left the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota isolated, as waters have washed away roads and left residents stranded for over two weeks.

And even after these floodwaters recede, problems will still be present. As noted in this article in Earther, for farmers, the floodwaters likely have washed away the nutrient-rich topsoil, leaving behind compacted soil, sand, and silt. It will take farmers years to build back soil as productive as what was just washed away into the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers.

[Modeled snow water equivalent (the amount of liquid water that would result if the snow all melted at once) values on March 11 and 28, 2019, for the Northern Plains, ranging from blue (10 inches or more) to pale green. Dark gray areas had no snow. In early March, a deep snowpack held 4-10 inches of liquid water in South Dakota, Minnesota, Iowa, and Wisconsin. By the end of March, a strong storm, heavy rain, and warming temperatures washed much of it over frozen ground and into nearby rivers. NOAA Climate image, based on data from NOHRSC.]

[Modeled snow water equivalent (the amount of liquid water that would result if the snow all melted at once) values on March 11 and 28, 2019, for the Northern Plains, ranging from blue (10 inches or more) to pale green. Dark gray areas had no snow. In early March, a deep snowpack held 4-10 inches of liquid water in South Dakota, Minnesota, Iowa, and Wisconsin. By the end of March, a strong storm, heavy rain, and warming temperatures washed much of it over frozen ground and into nearby rivers. NOAA Climate image, based on data from NOHRSC.]

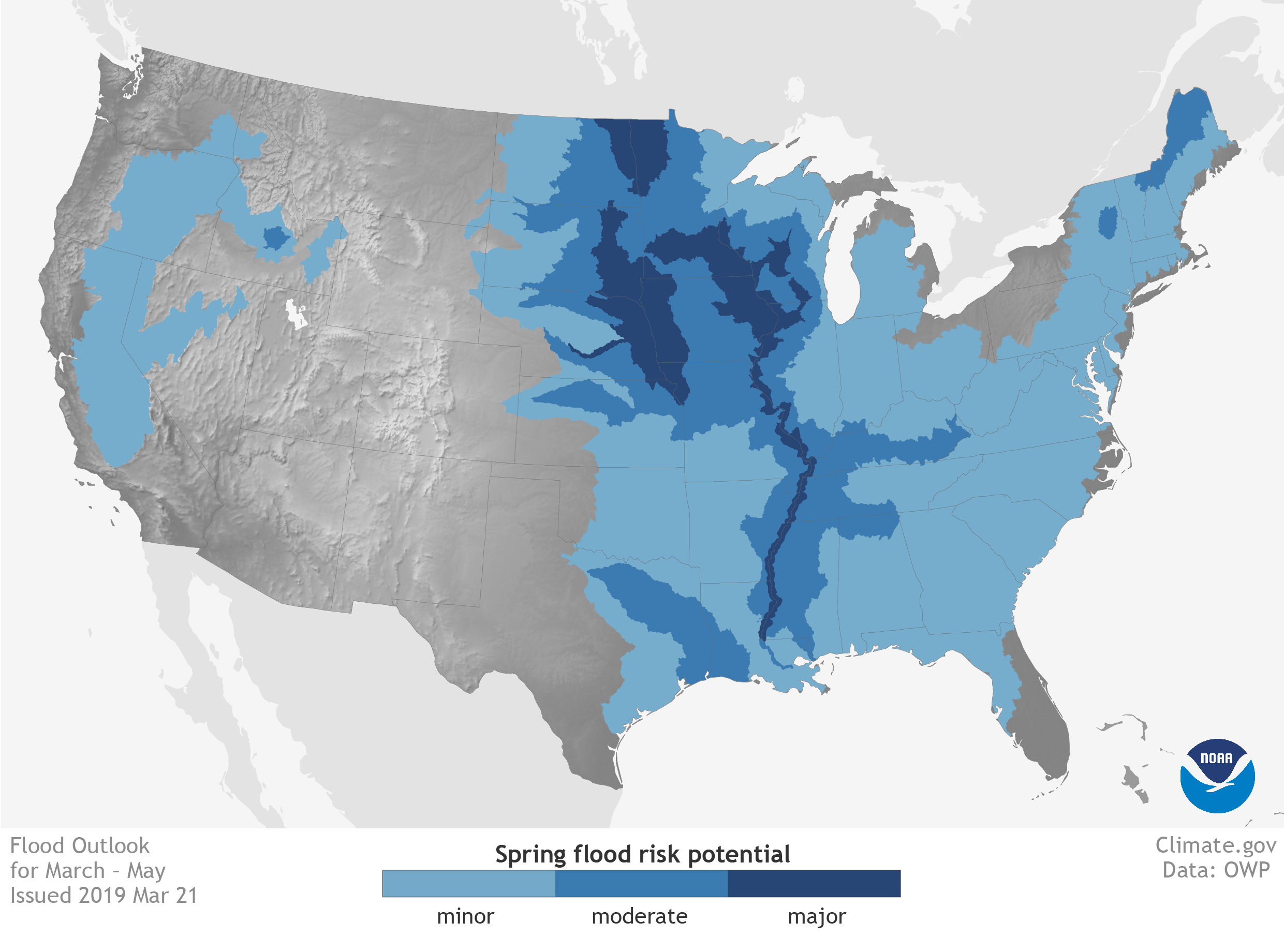

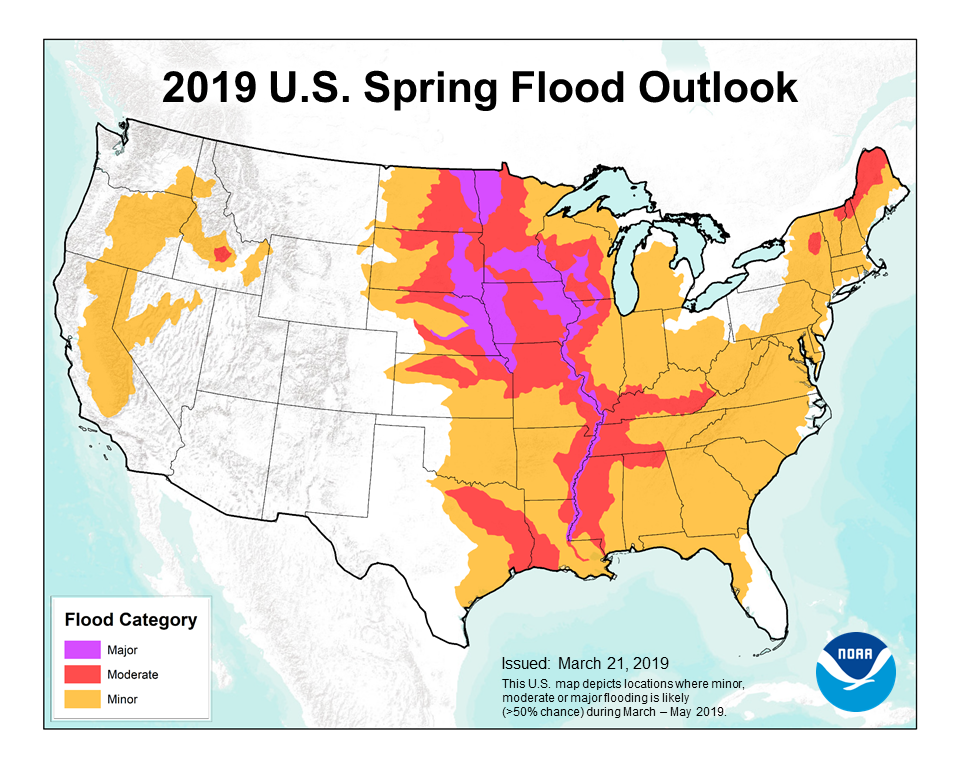

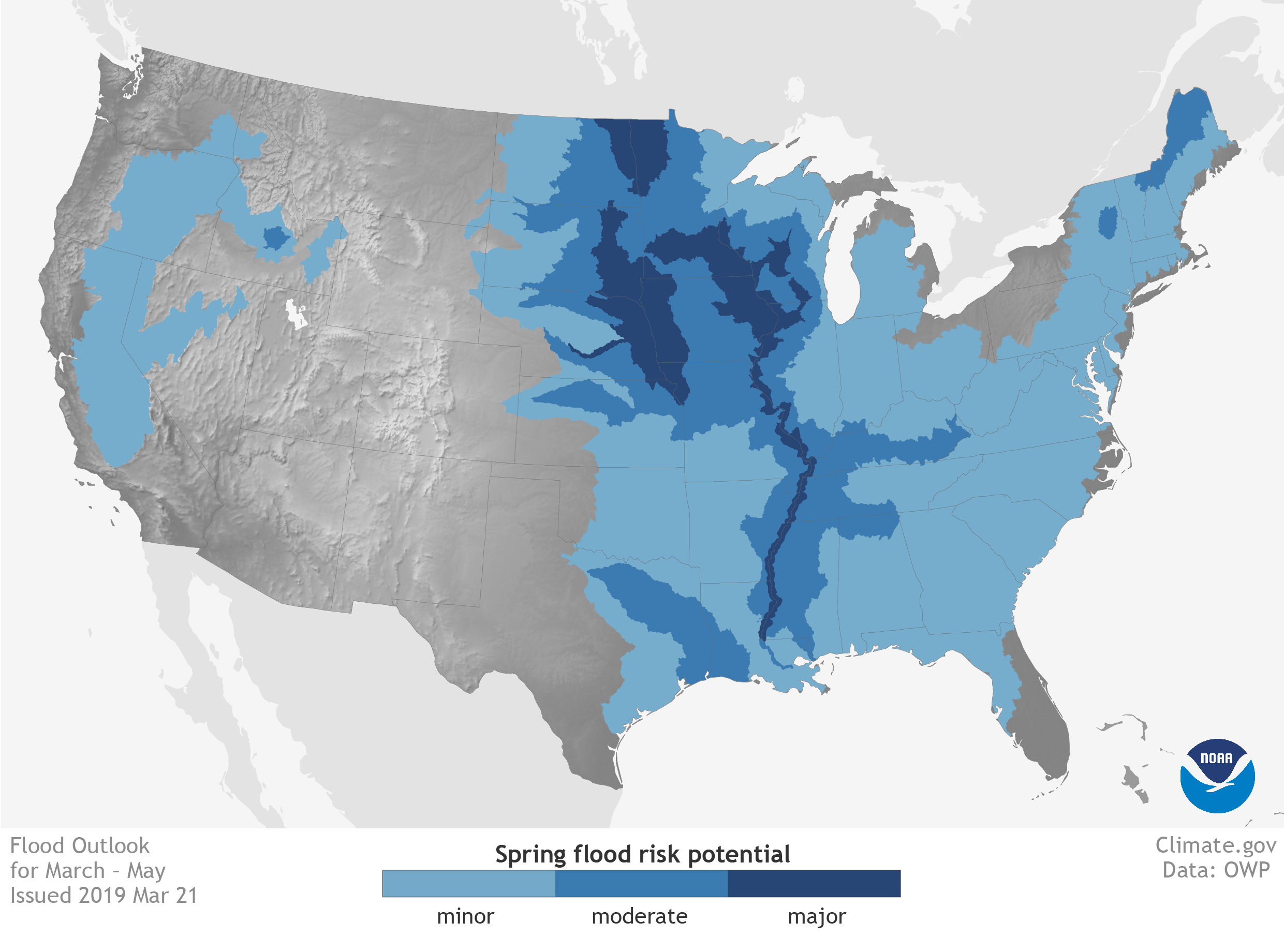

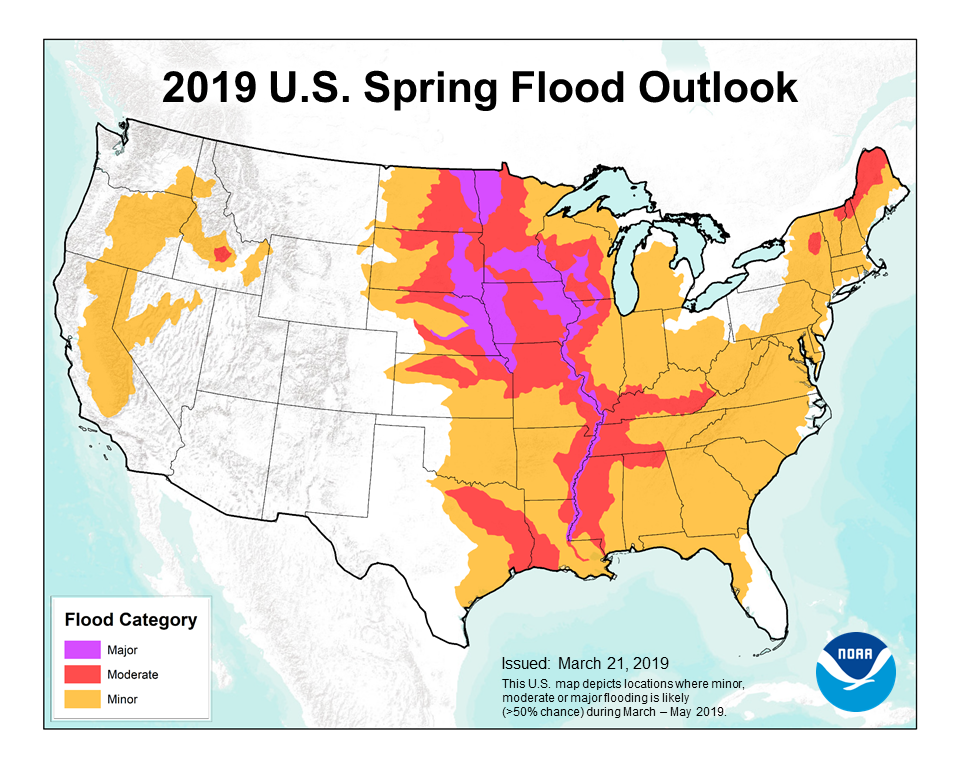

[U.S. areas at risk of minor (light blue), moderate (blue), and major (dark blue) flooding from March through May 2019. NOAA Climate map, based on data from the NWS Office of Water Prediction.]

[U.S. areas at risk of minor (light blue), moderate (blue), and major (dark blue) flooding from March through May 2019. NOAA Climate map, based on data from the NWS Office of Water Prediction.]

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace Michaels

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace Michaels

[Comparing the March 2018 (top) and March 2019 (bottom) satellite images of the Missouri River near Nebraska City, Nebraska. A checkerboard of farmland in the center of the 2018 image is submerged by muddy flood waters in 2019 as rain and snowmelt swell the Missouri River to more than five miles across in places. NOAA Climate images, based on Sentinel data from the European Space Agency.]

[Comparing the March 2018 (top) and March 2019 (bottom) satellite images of the Missouri River near Nebraska City, Nebraska. A checkerboard of farmland in the center of the 2018 image is submerged by muddy flood waters in 2019 as rain and snowmelt swell the Missouri River to more than five miles across in places. NOAA Climate images, based on Sentinel data from the European Space Agency.]

What happened?

A massive storm system barreled through the central United States during the second week of March bringing damaging winds, torrential rains, and blinding snow from Colorado to the Dakotas. And while all of this moisture from the storm itself ran off into the tributaries and creeks of the Missouri and Mississippi River systems, the most damaging impact of the storm was that in places where rain fell on snow, inches and inches of liquid water gushed across frozen ground into waterways in the Northern Plains. This massive release of liquid water led to the failures of levees in multiple states. The Des Moines Register reported that 17 levees were breached or overtopped along the Missouri River in Iowa, Nebraska, and Missouri. In Fremont County, Iowa, the Missouri River crested almost two feet above the previous record set in 2011. Neighboring Mills County saw river levels reach four feet above the previous record. The surge of water also led to flooding along the Elkhorn, Missouri, and Platte Rivers in Nebraska to name a few. Along the Niobrara River in northeastern Nebraska, the water overwhelmed and destroyed the Spencer Dam unleashing a wave of water downstream that eventually funneled into the fast-rising Missouri River. [Flood status for stream gauges across the central United States on March 29, 2019: major (dark blue), moderate (light blue), and minor (white). Numerous stream gauges across many rivers were in major flood status as of the end of March 2019, including gauges along the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers. A rapid melt of snow hastened by a strong spring storm led to a rapid rise in river levels across the Northern and Central Plains. NOAA Climate image, based on data from AHPS.]

The floods completely submerged towns and even lead to the evacuation of the National Weather Service office in Valley, Nebraska, located along the Platte River. Offutt Air Force Base also saw the neighboring river expand its boundaries onto the base, as the Missouri River and Papio Creek inundated southern portions of the base, including runways and about thirty buildings.

The governor of Nebraska, Pete Ricketts, estimated that preliminary and initial damage losses from the flooding in just Nebraska could be more than $1.3 billion with $440 million alone due to crop losses.

Farther north, the floodwaters have left the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota isolated, as waters have washed away roads and left residents stranded for over two weeks.

And even after these floodwaters recede, problems will still be present. As noted in this article in Earther, for farmers, the floodwaters likely have washed away the nutrient-rich topsoil, leaving behind compacted soil, sand, and silt. It will take farmers years to build back soil as productive as what was just washed away into the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers.

[Flood status for stream gauges across the central United States on March 29, 2019: major (dark blue), moderate (light blue), and minor (white). Numerous stream gauges across many rivers were in major flood status as of the end of March 2019, including gauges along the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers. A rapid melt of snow hastened by a strong spring storm led to a rapid rise in river levels across the Northern and Central Plains. NOAA Climate image, based on data from AHPS.]

The floods completely submerged towns and even lead to the evacuation of the National Weather Service office in Valley, Nebraska, located along the Platte River. Offutt Air Force Base also saw the neighboring river expand its boundaries onto the base, as the Missouri River and Papio Creek inundated southern portions of the base, including runways and about thirty buildings.

The governor of Nebraska, Pete Ricketts, estimated that preliminary and initial damage losses from the flooding in just Nebraska could be more than $1.3 billion with $440 million alone due to crop losses.

Farther north, the floodwaters have left the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota isolated, as waters have washed away roads and left residents stranded for over two weeks.

And even after these floodwaters recede, problems will still be present. As noted in this article in Earther, for farmers, the floodwaters likely have washed away the nutrient-rich topsoil, leaving behind compacted soil, sand, and silt. It will take farmers years to build back soil as productive as what was just washed away into the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers.

[Modeled snow water equivalent (the amount of liquid water that would result if the snow all melted at once) values on March 11 and 28, 2019, for the Northern Plains, ranging from blue (10 inches or more) to pale green. Dark gray areas had no snow. In early March, a deep snowpack held 4-10 inches of liquid water in South Dakota, Minnesota, Iowa, and Wisconsin. By the end of March, a strong storm, heavy rain, and warming temperatures washed much of it over frozen ground and into nearby rivers. NOAA Climate image, based on data from NOHRSC.]

[Modeled snow water equivalent (the amount of liquid water that would result if the snow all melted at once) values on March 11 and 28, 2019, for the Northern Plains, ranging from blue (10 inches or more) to pale green. Dark gray areas had no snow. In early March, a deep snowpack held 4-10 inches of liquid water in South Dakota, Minnesota, Iowa, and Wisconsin. By the end of March, a strong storm, heavy rain, and warming temperatures washed much of it over frozen ground and into nearby rivers. NOAA Climate image, based on data from NOHRSC.]

How much water was there?

Winter precipitation in 2018-19 was above average across virtually all of the Upper Midwest. After a freezing cold end to winter, the northern Plains was a frozen landscape with a dense snowpack that extended as far south as northern Kansas. In South Dakota alone, locked within the snow was 6 to 12 inches of liquid water ready to filter into nearby streams. Before the storm and subsequent flooding, a wide area across the northern Plains had three to six inches of liquid water stored as snow. During normal years, this snowmelt process can take place over the course of the whole spring, slowly entering creeks or being absorbed by the thawing soil. This gradual end to winter helps to reduce the general flood risk as rivers rise more slowly and not as high. But this year, all of that melting happened in roughly two weeks over soils that were still frozen and not as absorbent. This meant that rivers rose rapidly and incredibly high, easily overtopping the flood barriers many communities installed along the rivers to keep their towns safe. [U.S. areas at risk of minor (light blue), moderate (blue), and major (dark blue) flooding from March through May 2019. NOAA Climate map, based on data from the NWS Office of Water Prediction.]

[U.S. areas at risk of minor (light blue), moderate (blue), and major (dark blue) flooding from March through May 2019. NOAA Climate map, based on data from the NWS Office of Water Prediction.]

What’s going to happen for the rest of the spring?

Be sure to check out the 2019 Spring flood and climate outlook. Thanks to the wet winter, moist soils, the current flooding and forecasts for a wetter-than-average spring, major flooding is expected across the Plains for the rest of the spring. This includes major flooding along the Missouri River in South Dakota, Nebraska and northwestern Missouri, the Mississippi River, and the Red River Valley in North Dakota and western Minnesota. The worst case scenario would be if there is a rapid warm-up in temperatures combined with heavy rains across areas still with snow on the ground. Similar to the current floods, these conditions would result in a massive amount of water rushing into waterways leading to additional flooding. All of which means that this flooding story is far from over for many people in the central United States. In fact, for some, it may be just beginning. Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace Michaels

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace MichaelsAll Weather News

More