A Look back at the Southeast Tornado Outbreak from This Past Weekend

Special Stories

8 Mar 2019 9:56 AM

[NOAA by Tom Di Liberto] Tornadoes ravaged parts of Alabama and Georgia during the beginning of March 2019. The worst hit areas were located in Lee County, Alabama, along the eastern border with Georgia, where a strong tornado killed at least 23 people and injured dozens more.

https://www.facebook.com/WeatherNation/videos/414549259087563/

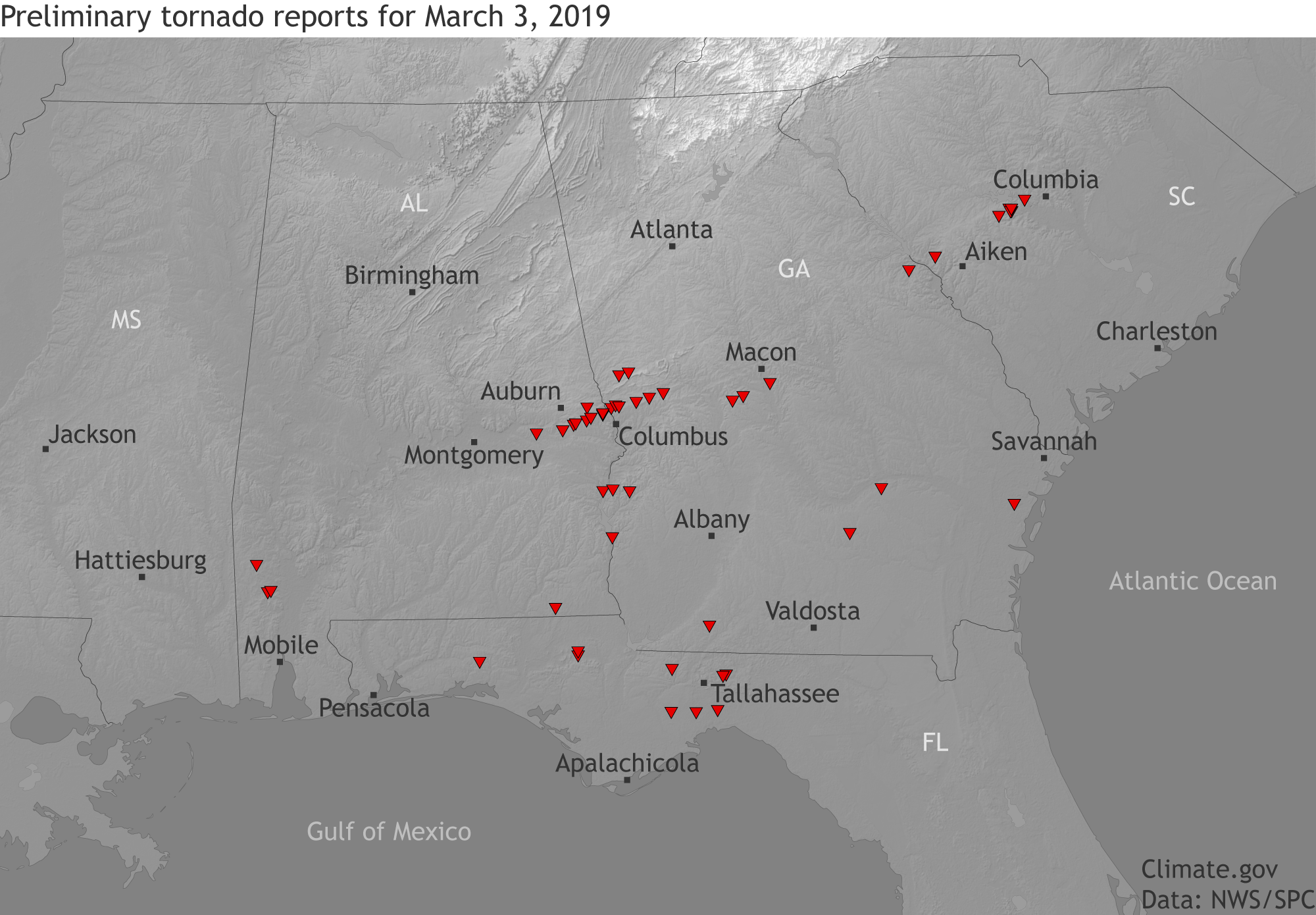

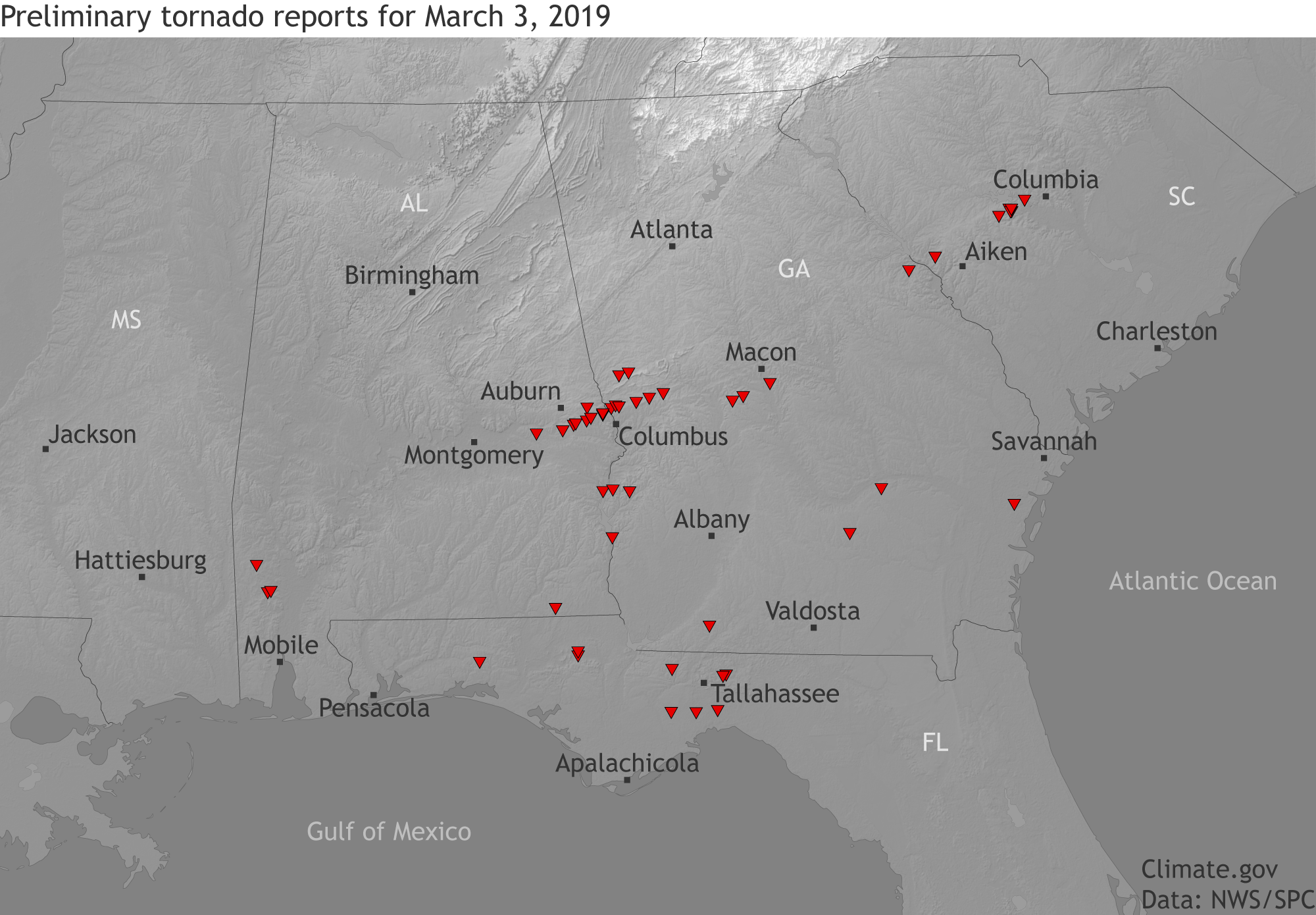

On March 3, a strong late-winter/early-spring storm system moved through the southeastern United States. As the conditions deteriorated, dozens of tornadoes—preliminary reports put the number at 40—formed across eastern Alabama, the panhandle of Florida, and western Georgia causing widespread damage. While many of these tornadoes tore down trees and damaged homes, it was the one in Lee County, Alabama, between the towns of Beauregard and Smiths Station that caused the most damage.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cNL9WT5N4Ss

[Violent storms moved across Alabama, Georgia and the Florida Panhandle on March 3, 2019, as seen here by the GOES East satellite's Geostationary Lightning Mapper (GLM). Toward the middle of this loop, you can see the result of daytime heating intensifying the storms and lightning, which is color-coded in shades of white to yellow. The GLM, which is the first operational lightning mapper flown in geostationary orbit, is capable of detecting in-cloud, cloud-to-cloud, and cloud-to-ground lightning activity over the Americas and adjacent ocean regions. Movie by NOAA NESDIS.]

Preliminarily rated as an EF-4 tornado—EF refers to the “enhanced Fujita scale” for ranking tornado severity. The EF scale ranks tornadoes based on damage and then estimates the winds based on that damage. An EF-4 tornado has winds greater than 166 mph. The twister touched down around 2 p.m. and left a trail of damage several miles long and a half a mile wide. It leveled buildings in its path, killing at least 23 people in the town of Beauregard. It was the deadliest tornado since 2013, and the first EF-4 tornado in the United States in almost two years.

Unfathomably, less than an hour later, a second tornado careened through nearly the exact same area in Lee County, Alabama. Elsewhere, a tornado nearly blew through Macon, Georgia, as multiple tornadoes spawned in Grady, Harris, and Talbot Counties in Georgia.

[The location of tornadoes across the southeastern United States on March 3, 2019. The tornado data was taken from storm reports from the Storm Prediction Center as of March 5 and is preliminary. On March 3, an outbreak of tornadoes ravaged the southeastern United States. The worst tornado killed over 20 people in eastern Alabama. Climate.gov image using data from the Storm Prediction Center.]

[The location of tornadoes across the southeastern United States on March 3, 2019. The tornado data was taken from storm reports from the Storm Prediction Center as of March 5 and is preliminary. On March 3, an outbreak of tornadoes ravaged the southeastern United States. The worst tornado killed over 20 people in eastern Alabama. Climate.gov image using data from the Storm Prediction Center.]

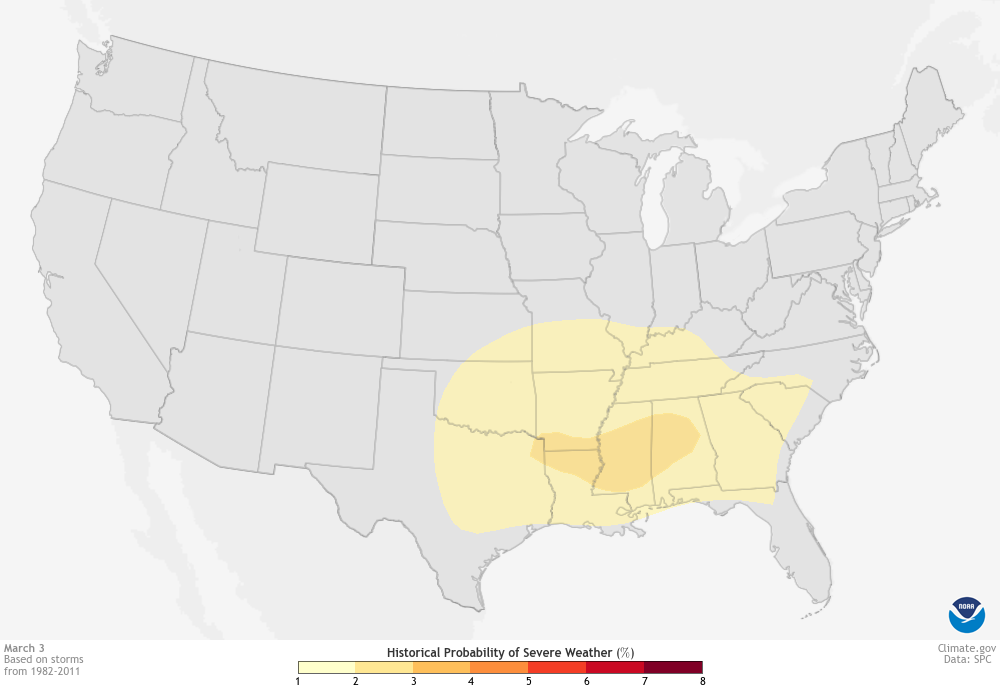

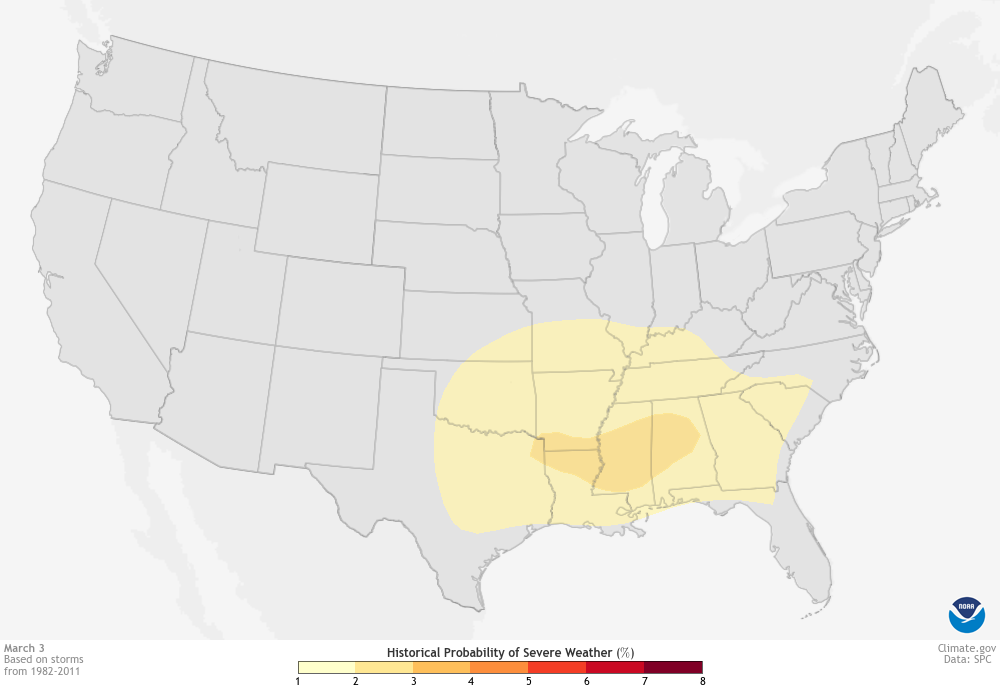

[Daily historic probability of severe weather within 25 miles of each map grid point during a 30-year base period for March 3. Darker colors represent a higher number of severe weather reports. In the beginning of March, the highest chance of severe weather is located in the Southeast. Map by NOAA Climate based on data from the Storm Prediction Center (SPC). Individual maps available from Data Snapshots.]

[Daily historic probability of severe weather within 25 miles of each map grid point during a 30-year base period for March 3. Darker colors represent a higher number of severe weather reports. In the beginning of March, the highest chance of severe weather is located in the Southeast. Map by NOAA Climate based on data from the Storm Prediction Center (SPC). Individual maps available from Data Snapshots.]

[Daily historic probability of severe weather within 25 miles of each map grid point during a 30-year base period for March 1-June 30, the peak of the yearly tornado season (April-June). Darker colors represent a higher number of severe weather reports. As spring progresses, the highest chance of severe weather spreads north and east across the Plains, the Midwest, and Southeast. Map by NOAA Climate based on data from the Storm Prediction Center (SPC). Individual maps available from Data Snapshots.]

During the beginning of March 2019, a large cold air mass pushed south across the eastern United States and created a large temperature difference between the relatively warm and humid Gulf Coast and the cold interior. This temperature contrast helped intensify the storm system that caused the deadly tornadoes.

In the Climate Science Special Report, which serves as the scientific foundation to the Fourth National Climate Assessment, released last year, scientists noted that tornadoes are exhibiting some changes that may be linked to climate change. Specifically, tornado activity in the United States has become more variable recently, with a decrease in the number of days with tornadoes, yet an increase in the number of tornadoes on days that have them. However, the current state of the science simply does not yet allow for a more detailed understanding of the cause of observed changes.

[Daily historic probability of severe weather within 25 miles of each map grid point during a 30-year base period for March 1-June 30, the peak of the yearly tornado season (April-June). Darker colors represent a higher number of severe weather reports. As spring progresses, the highest chance of severe weather spreads north and east across the Plains, the Midwest, and Southeast. Map by NOAA Climate based on data from the Storm Prediction Center (SPC). Individual maps available from Data Snapshots.]

During the beginning of March 2019, a large cold air mass pushed south across the eastern United States and created a large temperature difference between the relatively warm and humid Gulf Coast and the cold interior. This temperature contrast helped intensify the storm system that caused the deadly tornadoes.

In the Climate Science Special Report, which serves as the scientific foundation to the Fourth National Climate Assessment, released last year, scientists noted that tornadoes are exhibiting some changes that may be linked to climate change. Specifically, tornado activity in the United States has become more variable recently, with a decrease in the number of days with tornadoes, yet an increase in the number of tornadoes on days that have them. However, the current state of the science simply does not yet allow for a more detailed understanding of the cause of observed changes.

[Satellite animation from the geostationary satellite GOES East highlighting the deadly storms that hit Lee County, Alabama, as well as other parts of the Deep South on March 3, 2019. Created by our partners at the Cooperative Institute for Research in the Atmosphere, this kind of imagery is known as a "sandwich product" because it combines imagery from two of the 16 spectral channels offered by GOES-16's Advanced Baseline Imager: Band 2 (a visible band) and Band 13 (an infrared band). Here, red denotes the coldest cloud tops, which indicate areas of greater storm intensity. Image provided by NOAA's NESDIS.]

Additional research suggests that there have been regional changes in both reported tornadoes and the weather conditions favorable to tornado outbreaks over the recent decades. The authors of a 2018 study concluded that “Both tornado reports and [tornado-favorable] environments indicate significant decreasing trends in frequency over portions of Texas, Oklahoma, and northeast Colorado,” and “…significant increasing trends in portions of Mississippi, Alabama, Arkansas, Missouri, Illinois, Indiana, Tennessee, and Kentucky.” These patterns are indicative of a larger tendency for tornado outbreaks to occur east of the Mississippi River.

While those patterns are generally consistent with trends in severe weather predicted for the 21st Century by climate models, it’s not yet possible to confidently say whether the observed changes are due to human-caused climate change or natural variability. In part that’s because what climate models are usually projecting is not tornadoes themselves, but rather changes to environmental factors that could support an increase in the frequency and intensity of severe thunderstorms over areas which are prone to that type of hazard.

That approach is limited, however, because a severe thunderstorm doesn’t have to form, even given a friendly environment. And not every severe thunderstorm that forms will produce tornadoes. This is like how simply having the ingredients in your kitchen to make a cake doesn’t mean one automatically “poofs” into existence. Having certain atmospheric ingredients doesn’t necessarily guarantee a tornado. The atmosphere has to do some cooking first. Because of this, confidence in extrapolating future tornado behavior from projections of severe weather “ingredients” is low.

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace Michaels

[Satellite animation from the geostationary satellite GOES East highlighting the deadly storms that hit Lee County, Alabama, as well as other parts of the Deep South on March 3, 2019. Created by our partners at the Cooperative Institute for Research in the Atmosphere, this kind of imagery is known as a "sandwich product" because it combines imagery from two of the 16 spectral channels offered by GOES-16's Advanced Baseline Imager: Band 2 (a visible band) and Band 13 (an infrared band). Here, red denotes the coldest cloud tops, which indicate areas of greater storm intensity. Image provided by NOAA's NESDIS.]

Additional research suggests that there have been regional changes in both reported tornadoes and the weather conditions favorable to tornado outbreaks over the recent decades. The authors of a 2018 study concluded that “Both tornado reports and [tornado-favorable] environments indicate significant decreasing trends in frequency over portions of Texas, Oklahoma, and northeast Colorado,” and “…significant increasing trends in portions of Mississippi, Alabama, Arkansas, Missouri, Illinois, Indiana, Tennessee, and Kentucky.” These patterns are indicative of a larger tendency for tornado outbreaks to occur east of the Mississippi River.

While those patterns are generally consistent with trends in severe weather predicted for the 21st Century by climate models, it’s not yet possible to confidently say whether the observed changes are due to human-caused climate change or natural variability. In part that’s because what climate models are usually projecting is not tornadoes themselves, but rather changes to environmental factors that could support an increase in the frequency and intensity of severe thunderstorms over areas which are prone to that type of hazard.

That approach is limited, however, because a severe thunderstorm doesn’t have to form, even given a friendly environment. And not every severe thunderstorm that forms will produce tornadoes. This is like how simply having the ingredients in your kitchen to make a cake doesn’t mean one automatically “poofs” into existence. Having certain atmospheric ingredients doesn’t necessarily guarantee a tornado. The atmosphere has to do some cooking first. Because of this, confidence in extrapolating future tornado behavior from projections of severe weather “ingredients” is low.

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace Michaels

[The location of tornadoes across the southeastern United States on March 3, 2019. The tornado data was taken from storm reports from the Storm Prediction Center as of March 5 and is preliminary. On March 3, an outbreak of tornadoes ravaged the southeastern United States. The worst tornado killed over 20 people in eastern Alabama. Climate.gov image using data from the Storm Prediction Center.]

[The location of tornadoes across the southeastern United States on March 3, 2019. The tornado data was taken from storm reports from the Storm Prediction Center as of March 5 and is preliminary. On March 3, an outbreak of tornadoes ravaged the southeastern United States. The worst tornado killed over 20 people in eastern Alabama. Climate.gov image using data from the Storm Prediction Center.]

Is the southeast known for tornadoes?

Probably not to most of the country, but it should be. While we often think of the Great Plains as the domain of tornadoes, during the late winter/early spring, the highest chance of severe weather—which includes high winds, large hail, and tornadoes—shifts to the Gulf Coast, as the warm, moist air needed for outbreaks of severe weather retreats towards its home in the Gulf of Mexico. The historic probability of severe weather for the day of the deadly tornadoes, March 3, highlights this shift. The epicenter for highest risk is located across Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama with a broad area of risk located across the entire southeastern United States. The tornadoes that formed in the beginning of March may have missed the bullseye of highest chance but were still located within the area that historically has the highest chances for severe weather this time of year. [Daily historic probability of severe weather within 25 miles of each map grid point during a 30-year base period for March 3. Darker colors represent a higher number of severe weather reports. In the beginning of March, the highest chance of severe weather is located in the Southeast. Map by NOAA Climate based on data from the Storm Prediction Center (SPC). Individual maps available from Data Snapshots.]

[Daily historic probability of severe weather within 25 miles of each map grid point during a 30-year base period for March 3. Darker colors represent a higher number of severe weather reports. In the beginning of March, the highest chance of severe weather is located in the Southeast. Map by NOAA Climate based on data from the Storm Prediction Center (SPC). Individual maps available from Data Snapshots.]

Why is the Gulf Coast an area where tornadoes can form during early March?

Tornadoes are complex. The severe thunderstorms that form tornadoes are just as complex too. But the ingredients needed to create these storms is more straightforward. All the atmosphere needs is instability to allow air to rise easily, plenty of moisture to give any developing storm energy and, then, something to lift that air up to begin with. The addition of changing wind direction or speed with height introduces rotation into the mix, allowing a severe thunderstorm to potentially become tornadic. During winter and early spring, the repository for warm, moist air is normally contained in the southeastern United States close to its source, the Gulf of Mexico. And thus, so are the highest chances for severe weather. [Daily historic probability of severe weather within 25 miles of each map grid point during a 30-year base period for March 1-June 30, the peak of the yearly tornado season (April-June). Darker colors represent a higher number of severe weather reports. As spring progresses, the highest chance of severe weather spreads north and east across the Plains, the Midwest, and Southeast. Map by NOAA Climate based on data from the Storm Prediction Center (SPC). Individual maps available from Data Snapshots.]

During the beginning of March 2019, a large cold air mass pushed south across the eastern United States and created a large temperature difference between the relatively warm and humid Gulf Coast and the cold interior. This temperature contrast helped intensify the storm system that caused the deadly tornadoes.

In the Climate Science Special Report, which serves as the scientific foundation to the Fourth National Climate Assessment, released last year, scientists noted that tornadoes are exhibiting some changes that may be linked to climate change. Specifically, tornado activity in the United States has become more variable recently, with a decrease in the number of days with tornadoes, yet an increase in the number of tornadoes on days that have them. However, the current state of the science simply does not yet allow for a more detailed understanding of the cause of observed changes.

[Daily historic probability of severe weather within 25 miles of each map grid point during a 30-year base period for March 1-June 30, the peak of the yearly tornado season (April-June). Darker colors represent a higher number of severe weather reports. As spring progresses, the highest chance of severe weather spreads north and east across the Plains, the Midwest, and Southeast. Map by NOAA Climate based on data from the Storm Prediction Center (SPC). Individual maps available from Data Snapshots.]

During the beginning of March 2019, a large cold air mass pushed south across the eastern United States and created a large temperature difference between the relatively warm and humid Gulf Coast and the cold interior. This temperature contrast helped intensify the storm system that caused the deadly tornadoes.

In the Climate Science Special Report, which serves as the scientific foundation to the Fourth National Climate Assessment, released last year, scientists noted that tornadoes are exhibiting some changes that may be linked to climate change. Specifically, tornado activity in the United States has become more variable recently, with a decrease in the number of days with tornadoes, yet an increase in the number of tornadoes on days that have them. However, the current state of the science simply does not yet allow for a more detailed understanding of the cause of observed changes.

[Satellite animation from the geostationary satellite GOES East highlighting the deadly storms that hit Lee County, Alabama, as well as other parts of the Deep South on March 3, 2019. Created by our partners at the Cooperative Institute for Research in the Atmosphere, this kind of imagery is known as a "sandwich product" because it combines imagery from two of the 16 spectral channels offered by GOES-16's Advanced Baseline Imager: Band 2 (a visible band) and Band 13 (an infrared band). Here, red denotes the coldest cloud tops, which indicate areas of greater storm intensity. Image provided by NOAA's NESDIS.]

Additional research suggests that there have been regional changes in both reported tornadoes and the weather conditions favorable to tornado outbreaks over the recent decades. The authors of a 2018 study concluded that “Both tornado reports and [tornado-favorable] environments indicate significant decreasing trends in frequency over portions of Texas, Oklahoma, and northeast Colorado,” and “…significant increasing trends in portions of Mississippi, Alabama, Arkansas, Missouri, Illinois, Indiana, Tennessee, and Kentucky.” These patterns are indicative of a larger tendency for tornado outbreaks to occur east of the Mississippi River.

While those patterns are generally consistent with trends in severe weather predicted for the 21st Century by climate models, it’s not yet possible to confidently say whether the observed changes are due to human-caused climate change or natural variability. In part that’s because what climate models are usually projecting is not tornadoes themselves, but rather changes to environmental factors that could support an increase in the frequency and intensity of severe thunderstorms over areas which are prone to that type of hazard.

That approach is limited, however, because a severe thunderstorm doesn’t have to form, even given a friendly environment. And not every severe thunderstorm that forms will produce tornadoes. This is like how simply having the ingredients in your kitchen to make a cake doesn’t mean one automatically “poofs” into existence. Having certain atmospheric ingredients doesn’t necessarily guarantee a tornado. The atmosphere has to do some cooking first. Because of this, confidence in extrapolating future tornado behavior from projections of severe weather “ingredients” is low.

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace Michaels

[Satellite animation from the geostationary satellite GOES East highlighting the deadly storms that hit Lee County, Alabama, as well as other parts of the Deep South on March 3, 2019. Created by our partners at the Cooperative Institute for Research in the Atmosphere, this kind of imagery is known as a "sandwich product" because it combines imagery from two of the 16 spectral channels offered by GOES-16's Advanced Baseline Imager: Band 2 (a visible band) and Band 13 (an infrared band). Here, red denotes the coldest cloud tops, which indicate areas of greater storm intensity. Image provided by NOAA's NESDIS.]

Additional research suggests that there have been regional changes in both reported tornadoes and the weather conditions favorable to tornado outbreaks over the recent decades. The authors of a 2018 study concluded that “Both tornado reports and [tornado-favorable] environments indicate significant decreasing trends in frequency over portions of Texas, Oklahoma, and northeast Colorado,” and “…significant increasing trends in portions of Mississippi, Alabama, Arkansas, Missouri, Illinois, Indiana, Tennessee, and Kentucky.” These patterns are indicative of a larger tendency for tornado outbreaks to occur east of the Mississippi River.

While those patterns are generally consistent with trends in severe weather predicted for the 21st Century by climate models, it’s not yet possible to confidently say whether the observed changes are due to human-caused climate change or natural variability. In part that’s because what climate models are usually projecting is not tornadoes themselves, but rather changes to environmental factors that could support an increase in the frequency and intensity of severe thunderstorms over areas which are prone to that type of hazard.

That approach is limited, however, because a severe thunderstorm doesn’t have to form, even given a friendly environment. And not every severe thunderstorm that forms will produce tornadoes. This is like how simply having the ingredients in your kitchen to make a cake doesn’t mean one automatically “poofs” into existence. Having certain atmospheric ingredients doesn’t necessarily guarantee a tornado. The atmosphere has to do some cooking first. Because of this, confidence in extrapolating future tornado behavior from projections of severe weather “ingredients” is low.

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace MichaelsAll Weather News

More