Hurricane Experts Weigh in on Flood Insurance

Special Stories

21 May 2018 6:55 AM

[The Addicks neighborhood of Houston, Texas, sits in floodwaters after the heavy rains from Hurricane Harvey. (Image courtesy of the Harris County Flood Control District)]

From NOAA NHC

By now, billion-dollar flood disasters in the U.S. are something of an overlooked seasonal rite-of-passage. The Midwest flooding of April 2017 feels like a distant memory, as does the California flooding two months before it, Hurricane Matthew’s historic flooding the fall before that, the devastating floods in Louisiana the summer before that, and Texas and Louisiana — again — the spring before that. Some 500,000 homes damaged or destroyed at a cost of more than $150 billion in two years from those events alone. No one expected that kind of flooding to affect them. They never do.

For Hurricane Harvey, its Category 4 winds at landfall were just a prelude of things to come. Harvey wasn’t even a hurricane by the time its heaviest rains reached Houston. Though the tropical storm’s still-high winds hampered rescue efforts, the winds were not at the forefront of the minds’ of residents living through the unimaginable. The magnitude of the flood nightmare caught even Houston, no stranger to big floods, by surprise. Three to five feet of rainwater poured down from the skies above in what would become the worst freshwater flood in United States history. The residences of nearly one-in-three people in America’s fourth-largest city were under water.

In Harvey’s wake lay a dizzying disbelief of devastation. More than 120,000 homes in Harris County, where Houston is located, were damaged by floodwaters.[1] What’s more, an estimated 70 percent of those homes were uninsured for floods.[1],[2] That meant the majority of Houstonians, not the insurance companies, were on the hook for the bill. The best-case scenario for uninsured survivors was Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) disaster assistance (typically ranging $3,000–$8,000) or a U.S. Small Business Administration (SBA) low-interest federal loan (up to $200,000 for home repair). In reality, covering the cost of repairs for most came from a combination of federal assistance and personal finances, which for many meant adding to or incurring new consumer debt.

It was never intended for the federal government to bail out the uninsured after a disaster— in fact, quite the opposite. When the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) was established 50 years ago, its goal was to help insure the uninsured before a disaster. Flooding is the most common and expensive type of disaster, and insuring high-risk flood areas often demands an astronomical price tag. Back in the 1960s, private market flood insurance simply wasn’t available. This is where the NFIP came in. Through the NFIP, the federal government began offering largely affordable policies to the residents of participating communities who adopted and enforced floodplain management ordinances in high-risk flood areas to reduce future flood risk. In theory, securing and insuring high-risk communities reduces the reliance on federal post-disaster assistance and saves the government (and U.S. taxpayers) money, which is a good thing.

Flood insurance, once voluntary, is today required for all properties with federally-backed mortgages in high-risk flood areas. To define these high-risk flood areas, FEMA routinely conducts flood hazard analyses to identify land areas at risk of being inundated by a flood that has a 1 percent chance of being equaled or exceeded in any given year. Since 1 percent is interchangeable with 1-in-100, these high-risk floods have become known as 1-in-100 year (or 100-year) floods. FEMA designates these so-called 100-year floodplains as Special Flood Hazard Areas (SFHAs).

Which brings us back to Houston. When Harvey’s floodwaters receded, some 2-in-3 survivors had no insurance to cover their flood losses.1,2 The vast majority of flooding during Harvey happened outside of the SFHA. The storm widened rivers and reservoirs to a point where roads became riverbeds. When everything’s flooded, flood zones feel a little meaningless. But one of the lessons Harvey taught is that flood zones, and our understanding of them, do matter — more so today than ever.

It was never intended for the federal government to bail out the uninsured after a disaster— in fact, quite the opposite. When the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) was established 50 years ago, its goal was to help insure the uninsured before a disaster. Flooding is the most common and expensive type of disaster, and insuring high-risk flood areas often demands an astronomical price tag. Back in the 1960s, private market flood insurance simply wasn’t available. This is where the NFIP came in. Through the NFIP, the federal government began offering largely affordable policies to the residents of participating communities who adopted and enforced floodplain management ordinances in high-risk flood areas to reduce future flood risk. In theory, securing and insuring high-risk communities reduces the reliance on federal post-disaster assistance and saves the government (and U.S. taxpayers) money, which is a good thing.

Flood insurance, once voluntary, is today required for all properties with federally-backed mortgages in high-risk flood areas. To define these high-risk flood areas, FEMA routinely conducts flood hazard analyses to identify land areas at risk of being inundated by a flood that has a 1 percent chance of being equaled or exceeded in any given year. Since 1 percent is interchangeable with 1-in-100, these high-risk floods have become known as 1-in-100 year (or 100-year) floods. FEMA designates these so-called 100-year floodplains as Special Flood Hazard Areas (SFHAs).

Which brings us back to Houston. When Harvey’s floodwaters receded, some 2-in-3 survivors had no insurance to cover their flood losses.1,2 The vast majority of flooding during Harvey happened outside of the SFHA. The storm widened rivers and reservoirs to a point where roads became riverbeds. When everything’s flooded, flood zones feel a little meaningless. But one of the lessons Harvey taught is that flood zones, and our understanding of them, do matter — more so today than ever.

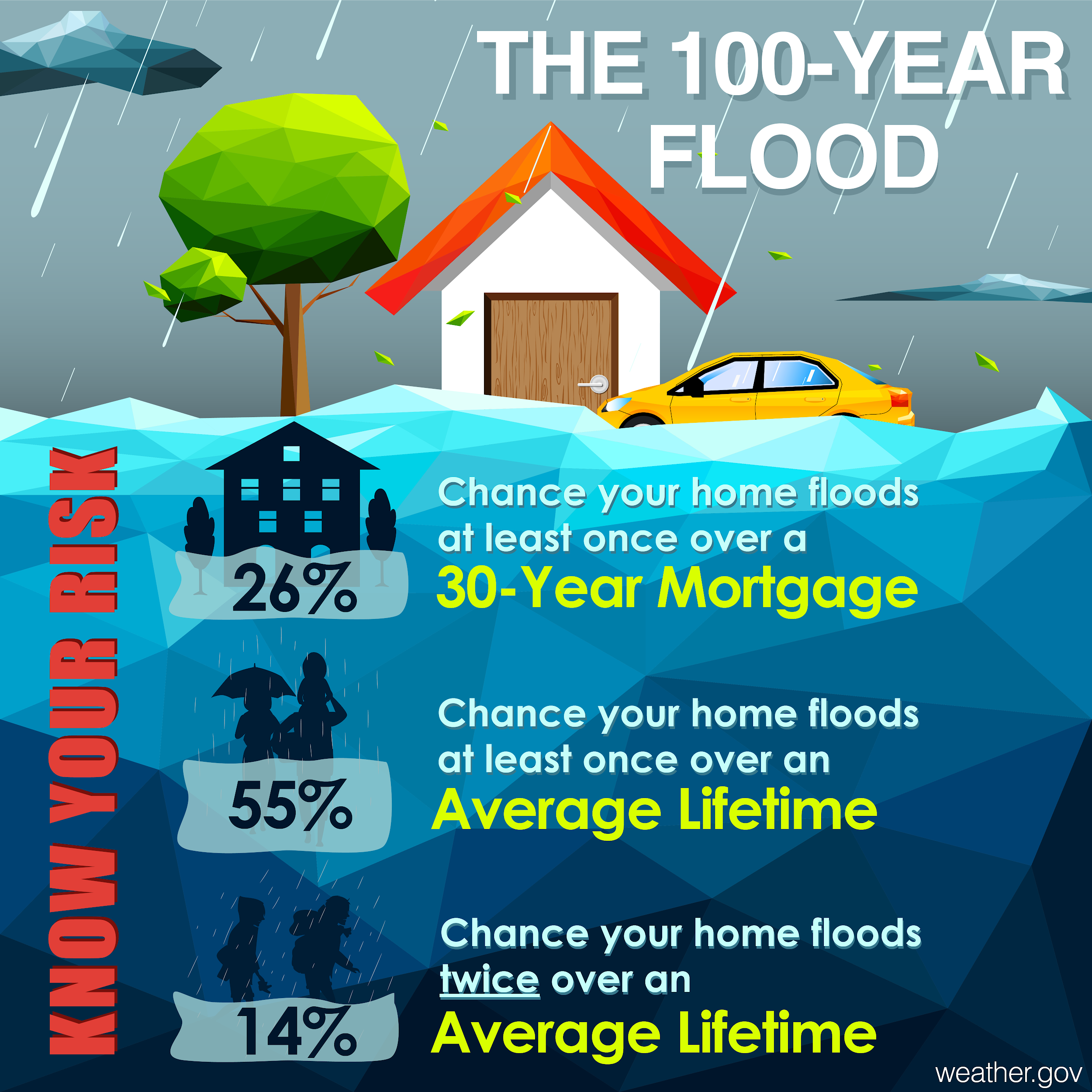

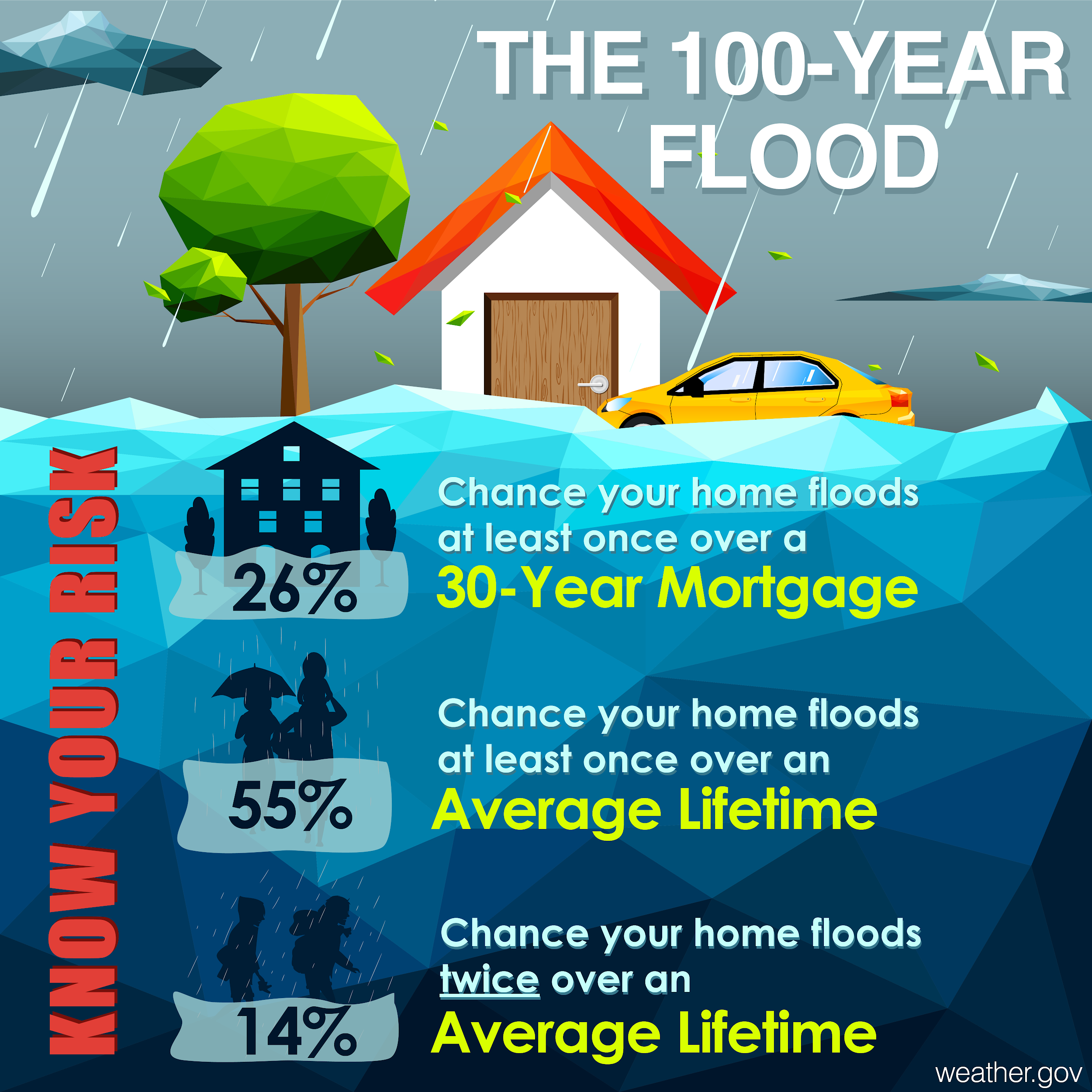

The so-called 100-year floodplain can be understandably confusing. A 1 percent chance of anything happening in a given year feels remote, but most of us don’t live in our houses for a single year. Consider, for example, a 30-year mortgage. The odds of one of those 100-year floods happening over the period of a 30-year mortgage is about 1 in 4. A 25 percent chance of a devastating flood over the period of your mortgage are higher than the odds of a devastating house fire, and you probably wouldn’t go 30 years without installing smoke detectors in your home.

It’s easy to see the need for flood insurance when it’s required; it’s not as clear when it isn’t. So what about those living in high-risk areas without a federally-backed mortgage? Or what about those living outside the high-risk, 100-year floodplain? After all, a moderate chance of flooding hardly implies you’re safe. In fact, FEMA estimates that nearly 1 in 4 of all federal flood claims occur outside of high-risk areas. As every billion-dollar flood disaster shows, floods can be some of the most egregious rule breakers.

Financial decisions, including whether to insure your home and belongings from a flood, are deeply personal family issues. They often aren’t easy decisions, even for those most familiar with the threat. Below, two of the nation’s leading hurricane experts discuss their own experiences living in places where water is a stark reality. Though the aim of their livelihoods is piecing together the clues of Mother Nature’s next step, they’ve each lived through the unpredictable moments. The billion-dollar floods don’t get any easier, and as coastal populations soar, neither will the decisions that shield us from Mother Nature’s most unpredictable moments.

The so-called 100-year floodplain can be understandably confusing. A 1 percent chance of anything happening in a given year feels remote, but most of us don’t live in our houses for a single year. Consider, for example, a 30-year mortgage. The odds of one of those 100-year floods happening over the period of a 30-year mortgage is about 1 in 4. A 25 percent chance of a devastating flood over the period of your mortgage are higher than the odds of a devastating house fire, and you probably wouldn’t go 30 years without installing smoke detectors in your home.

It’s easy to see the need for flood insurance when it’s required; it’s not as clear when it isn’t. So what about those living in high-risk areas without a federally-backed mortgage? Or what about those living outside the high-risk, 100-year floodplain? After all, a moderate chance of flooding hardly implies you’re safe. In fact, FEMA estimates that nearly 1 in 4 of all federal flood claims occur outside of high-risk areas. As every billion-dollar flood disaster shows, floods can be some of the most egregious rule breakers.

Financial decisions, including whether to insure your home and belongings from a flood, are deeply personal family issues. They often aren’t easy decisions, even for those most familiar with the threat. Below, two of the nation’s leading hurricane experts discuss their own experiences living in places where water is a stark reality. Though the aim of their livelihoods is piecing together the clues of Mother Nature’s next step, they’ve each lived through the unpredictable moments. The billion-dollar floods don’t get any easier, and as coastal populations soar, neither will the decisions that shield us from Mother Nature’s most unpredictable moments.

[A golf buddy of Bill Read and the man’s son move four of the son’s dogs to higher ground after Harvey flooded League City, Texas.]

I think a big problem people have is differentiating between “requiring” and “needing” flood insurance. My first exposure to the issue of “needing” flood insurance occurred when we moved from Maryland to League City, Texas, in 1992. The house we decided to purchase was (barely) outside the floodplain indicating the 100-year elevation. However, I was concerned about the risk mainly due to storm surge, as data indicated a Category 3 hurricane or above would bring water levels above the level of our home’s foundation. Our realtor and our lender were both adamant in telling us we didn’t “need” flood insurance. I asked our insurance agent at USAA and he was spot on in differentiating between “required” and “needed”. We chose to follow our insurer’s advice. When we decided to move to a new house in 2005, I found a development on the lowest flood risk land in League City, a parcel that sat outside the 500-year elevation. While no longer in a storm surge risk area, I was concerned about flooding from an “off the charts” rain event. Interestingly, my realtor for this move was savvy about flooding along the Gulf coast and advised us to keep flood insurance, as did USAA, which I had already decided I would do based on the many floods I had witnessed outside the 100-year risk areas in Houston since 1992. Along came Harvey, and although we did not flood from the 45 inches of rain we received, the water reached our porch and was one inch from entering the house. Six of my friends were not as fortunate, and two of them did not have flood insurance. Needless to say, when my policy came up for renewal in February, I quickly did so!

[A golf buddy of Bill Read and the man’s son move four of the son’s dogs to higher ground after Harvey flooded League City, Texas.]

I think a big problem people have is differentiating between “requiring” and “needing” flood insurance. My first exposure to the issue of “needing” flood insurance occurred when we moved from Maryland to League City, Texas, in 1992. The house we decided to purchase was (barely) outside the floodplain indicating the 100-year elevation. However, I was concerned about the risk mainly due to storm surge, as data indicated a Category 3 hurricane or above would bring water levels above the level of our home’s foundation. Our realtor and our lender were both adamant in telling us we didn’t “need” flood insurance. I asked our insurance agent at USAA and he was spot on in differentiating between “required” and “needed”. We chose to follow our insurer’s advice. When we decided to move to a new house in 2005, I found a development on the lowest flood risk land in League City, a parcel that sat outside the 500-year elevation. While no longer in a storm surge risk area, I was concerned about flooding from an “off the charts” rain event. Interestingly, my realtor for this move was savvy about flooding along the Gulf coast and advised us to keep flood insurance, as did USAA, which I had already decided I would do based on the many floods I had witnessed outside the 100-year risk areas in Houston since 1992. Along came Harvey, and although we did not flood from the 45 inches of rain we received, the water reached our porch and was one inch from entering the house. Six of my friends were not as fortunate, and two of them did not have flood insurance. Needless to say, when my policy came up for renewal in February, I quickly did so!

[Debris lies the street of one of Bill Read’s friends in Dickinson, Texas, two months after Harvey flooded the area.]

[Debris lies the street of one of Bill Read’s friends in Dickinson, Texas, two months after Harvey flooded the area.]

[Street flooding from a heavy rain event in Jamie’s former South Florida neighborhood in October 2017. When drains are clogged by debris, streets easily flood with water creeping up driveways.]

I recently purchased a home in South Florida, and while going through the mortgage approval process, was informed that the home was outside of the high-risk area (aka the 100-year flood zone) and thus flood insurance wasn’t “required.” I’m also far enough inland to prevent storm surge (saltwater) inundation. However, the home is situated near a freshwater lake, and South Florida often experiences very heavy rains, sometimes exceeding 10 inches in a day. One can easily envision a scenario where debris, from heavy rains or winds, clogs the storm water drains and water pools in the street, eventually coming up the driveway and ultimately wetting the bottom floor of my home. Indeed, South Floridians are very accustomed to this very issue as it frequently occurs during our rainy season. Without flood insurance, I as the homeowner would be responsible for all the damage, which can easily climb into the thousands of dollars. Imagine replacing floors, walls, furniture, possessions, etc., and then taking steps to prevent mold. Given the small cost of flood insurance, the decision was an easy one and I determined that flood insurance was “needed” even if it wasn’t “required.” I was also lucky enough to have a realtor who was well-informed on flood insurance and overall flood risk. He encouraged the purchase of flood insurance citing his experience living in Florida and personal experience with freshwater flooding. Not all home buyers benefit from such well-informed or well-intentioned realtors and home buyers often navigate these complicated waters on their own. If in doubt, it’s better to be safe than sorry.

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace Michaels

[Street flooding from a heavy rain event in Jamie’s former South Florida neighborhood in October 2017. When drains are clogged by debris, streets easily flood with water creeping up driveways.]

I recently purchased a home in South Florida, and while going through the mortgage approval process, was informed that the home was outside of the high-risk area (aka the 100-year flood zone) and thus flood insurance wasn’t “required.” I’m also far enough inland to prevent storm surge (saltwater) inundation. However, the home is situated near a freshwater lake, and South Florida often experiences very heavy rains, sometimes exceeding 10 inches in a day. One can easily envision a scenario where debris, from heavy rains or winds, clogs the storm water drains and water pools in the street, eventually coming up the driveway and ultimately wetting the bottom floor of my home. Indeed, South Floridians are very accustomed to this very issue as it frequently occurs during our rainy season. Without flood insurance, I as the homeowner would be responsible for all the damage, which can easily climb into the thousands of dollars. Imagine replacing floors, walls, furniture, possessions, etc., and then taking steps to prevent mold. Given the small cost of flood insurance, the decision was an easy one and I determined that flood insurance was “needed” even if it wasn’t “required.” I was also lucky enough to have a realtor who was well-informed on flood insurance and overall flood risk. He encouraged the purchase of flood insurance citing his experience living in Florida and personal experience with freshwater flooding. Not all home buyers benefit from such well-informed or well-intentioned realtors and home buyers often navigate these complicated waters on their own. If in doubt, it’s better to be safe than sorry.

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace Michaels

It was never intended for the federal government to bail out the uninsured after a disaster— in fact, quite the opposite. When the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) was established 50 years ago, its goal was to help insure the uninsured before a disaster. Flooding is the most common and expensive type of disaster, and insuring high-risk flood areas often demands an astronomical price tag. Back in the 1960s, private market flood insurance simply wasn’t available. This is where the NFIP came in. Through the NFIP, the federal government began offering largely affordable policies to the residents of participating communities who adopted and enforced floodplain management ordinances in high-risk flood areas to reduce future flood risk. In theory, securing and insuring high-risk communities reduces the reliance on federal post-disaster assistance and saves the government (and U.S. taxpayers) money, which is a good thing.

Flood insurance, once voluntary, is today required for all properties with federally-backed mortgages in high-risk flood areas. To define these high-risk flood areas, FEMA routinely conducts flood hazard analyses to identify land areas at risk of being inundated by a flood that has a 1 percent chance of being equaled or exceeded in any given year. Since 1 percent is interchangeable with 1-in-100, these high-risk floods have become known as 1-in-100 year (or 100-year) floods. FEMA designates these so-called 100-year floodplains as Special Flood Hazard Areas (SFHAs).

Which brings us back to Houston. When Harvey’s floodwaters receded, some 2-in-3 survivors had no insurance to cover their flood losses.1,2 The vast majority of flooding during Harvey happened outside of the SFHA. The storm widened rivers and reservoirs to a point where roads became riverbeds. When everything’s flooded, flood zones feel a little meaningless. But one of the lessons Harvey taught is that flood zones, and our understanding of them, do matter — more so today than ever.

It was never intended for the federal government to bail out the uninsured after a disaster— in fact, quite the opposite. When the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) was established 50 years ago, its goal was to help insure the uninsured before a disaster. Flooding is the most common and expensive type of disaster, and insuring high-risk flood areas often demands an astronomical price tag. Back in the 1960s, private market flood insurance simply wasn’t available. This is where the NFIP came in. Through the NFIP, the federal government began offering largely affordable policies to the residents of participating communities who adopted and enforced floodplain management ordinances in high-risk flood areas to reduce future flood risk. In theory, securing and insuring high-risk communities reduces the reliance on federal post-disaster assistance and saves the government (and U.S. taxpayers) money, which is a good thing.

Flood insurance, once voluntary, is today required for all properties with federally-backed mortgages in high-risk flood areas. To define these high-risk flood areas, FEMA routinely conducts flood hazard analyses to identify land areas at risk of being inundated by a flood that has a 1 percent chance of being equaled or exceeded in any given year. Since 1 percent is interchangeable with 1-in-100, these high-risk floods have become known as 1-in-100 year (or 100-year) floods. FEMA designates these so-called 100-year floodplains as Special Flood Hazard Areas (SFHAs).

Which brings us back to Houston. When Harvey’s floodwaters receded, some 2-in-3 survivors had no insurance to cover their flood losses.1,2 The vast majority of flooding during Harvey happened outside of the SFHA. The storm widened rivers and reservoirs to a point where roads became riverbeds. When everything’s flooded, flood zones feel a little meaningless. But one of the lessons Harvey taught is that flood zones, and our understanding of them, do matter — more so today than ever.

The so-called 100-year floodplain can be understandably confusing. A 1 percent chance of anything happening in a given year feels remote, but most of us don’t live in our houses for a single year. Consider, for example, a 30-year mortgage. The odds of one of those 100-year floods happening over the period of a 30-year mortgage is about 1 in 4. A 25 percent chance of a devastating flood over the period of your mortgage are higher than the odds of a devastating house fire, and you probably wouldn’t go 30 years without installing smoke detectors in your home.

It’s easy to see the need for flood insurance when it’s required; it’s not as clear when it isn’t. So what about those living in high-risk areas without a federally-backed mortgage? Or what about those living outside the high-risk, 100-year floodplain? After all, a moderate chance of flooding hardly implies you’re safe. In fact, FEMA estimates that nearly 1 in 4 of all federal flood claims occur outside of high-risk areas. As every billion-dollar flood disaster shows, floods can be some of the most egregious rule breakers.

Financial decisions, including whether to insure your home and belongings from a flood, are deeply personal family issues. They often aren’t easy decisions, even for those most familiar with the threat. Below, two of the nation’s leading hurricane experts discuss their own experiences living in places where water is a stark reality. Though the aim of their livelihoods is piecing together the clues of Mother Nature’s next step, they’ve each lived through the unpredictable moments. The billion-dollar floods don’t get any easier, and as coastal populations soar, neither will the decisions that shield us from Mother Nature’s most unpredictable moments.

The so-called 100-year floodplain can be understandably confusing. A 1 percent chance of anything happening in a given year feels remote, but most of us don’t live in our houses for a single year. Consider, for example, a 30-year mortgage. The odds of one of those 100-year floods happening over the period of a 30-year mortgage is about 1 in 4. A 25 percent chance of a devastating flood over the period of your mortgage are higher than the odds of a devastating house fire, and you probably wouldn’t go 30 years without installing smoke detectors in your home.

It’s easy to see the need for flood insurance when it’s required; it’s not as clear when it isn’t. So what about those living in high-risk areas without a federally-backed mortgage? Or what about those living outside the high-risk, 100-year floodplain? After all, a moderate chance of flooding hardly implies you’re safe. In fact, FEMA estimates that nearly 1 in 4 of all federal flood claims occur outside of high-risk areas. As every billion-dollar flood disaster shows, floods can be some of the most egregious rule breakers.

Financial decisions, including whether to insure your home and belongings from a flood, are deeply personal family issues. They often aren’t easy decisions, even for those most familiar with the threat. Below, two of the nation’s leading hurricane experts discuss their own experiences living in places where water is a stark reality. Though the aim of their livelihoods is piecing together the clues of Mother Nature’s next step, they’ve each lived through the unpredictable moments. The billion-dollar floods don’t get any easier, and as coastal populations soar, neither will the decisions that shield us from Mother Nature’s most unpredictable moments.

Bill Read, Former Director, National Hurricane Center

[A golf buddy of Bill Read and the man’s son move four of the son’s dogs to higher ground after Harvey flooded League City, Texas.]

I think a big problem people have is differentiating between “requiring” and “needing” flood insurance. My first exposure to the issue of “needing” flood insurance occurred when we moved from Maryland to League City, Texas, in 1992. The house we decided to purchase was (barely) outside the floodplain indicating the 100-year elevation. However, I was concerned about the risk mainly due to storm surge, as data indicated a Category 3 hurricane or above would bring water levels above the level of our home’s foundation. Our realtor and our lender were both adamant in telling us we didn’t “need” flood insurance. I asked our insurance agent at USAA and he was spot on in differentiating between “required” and “needed”. We chose to follow our insurer’s advice. When we decided to move to a new house in 2005, I found a development on the lowest flood risk land in League City, a parcel that sat outside the 500-year elevation. While no longer in a storm surge risk area, I was concerned about flooding from an “off the charts” rain event. Interestingly, my realtor for this move was savvy about flooding along the Gulf coast and advised us to keep flood insurance, as did USAA, which I had already decided I would do based on the many floods I had witnessed outside the 100-year risk areas in Houston since 1992. Along came Harvey, and although we did not flood from the 45 inches of rain we received, the water reached our porch and was one inch from entering the house. Six of my friends were not as fortunate, and two of them did not have flood insurance. Needless to say, when my policy came up for renewal in February, I quickly did so!

[A golf buddy of Bill Read and the man’s son move four of the son’s dogs to higher ground after Harvey flooded League City, Texas.]

I think a big problem people have is differentiating between “requiring” and “needing” flood insurance. My first exposure to the issue of “needing” flood insurance occurred when we moved from Maryland to League City, Texas, in 1992. The house we decided to purchase was (barely) outside the floodplain indicating the 100-year elevation. However, I was concerned about the risk mainly due to storm surge, as data indicated a Category 3 hurricane or above would bring water levels above the level of our home’s foundation. Our realtor and our lender were both adamant in telling us we didn’t “need” flood insurance. I asked our insurance agent at USAA and he was spot on in differentiating between “required” and “needed”. We chose to follow our insurer’s advice. When we decided to move to a new house in 2005, I found a development on the lowest flood risk land in League City, a parcel that sat outside the 500-year elevation. While no longer in a storm surge risk area, I was concerned about flooding from an “off the charts” rain event. Interestingly, my realtor for this move was savvy about flooding along the Gulf coast and advised us to keep flood insurance, as did USAA, which I had already decided I would do based on the many floods I had witnessed outside the 100-year risk areas in Houston since 1992. Along came Harvey, and although we did not flood from the 45 inches of rain we received, the water reached our porch and was one inch from entering the house. Six of my friends were not as fortunate, and two of them did not have flood insurance. Needless to say, when my policy came up for renewal in February, I quickly did so!

[Debris lies the street of one of Bill Read’s friends in Dickinson, Texas, two months after Harvey flooded the area.]

[Debris lies the street of one of Bill Read’s friends in Dickinson, Texas, two months after Harvey flooded the area.]

Jamie Rhome, Storm Surge Specialist, National Hurricane Center

[Street flooding from a heavy rain event in Jamie’s former South Florida neighborhood in October 2017. When drains are clogged by debris, streets easily flood with water creeping up driveways.]

I recently purchased a home in South Florida, and while going through the mortgage approval process, was informed that the home was outside of the high-risk area (aka the 100-year flood zone) and thus flood insurance wasn’t “required.” I’m also far enough inland to prevent storm surge (saltwater) inundation. However, the home is situated near a freshwater lake, and South Florida often experiences very heavy rains, sometimes exceeding 10 inches in a day. One can easily envision a scenario where debris, from heavy rains or winds, clogs the storm water drains and water pools in the street, eventually coming up the driveway and ultimately wetting the bottom floor of my home. Indeed, South Floridians are very accustomed to this very issue as it frequently occurs during our rainy season. Without flood insurance, I as the homeowner would be responsible for all the damage, which can easily climb into the thousands of dollars. Imagine replacing floors, walls, furniture, possessions, etc., and then taking steps to prevent mold. Given the small cost of flood insurance, the decision was an easy one and I determined that flood insurance was “needed” even if it wasn’t “required.” I was also lucky enough to have a realtor who was well-informed on flood insurance and overall flood risk. He encouraged the purchase of flood insurance citing his experience living in Florida and personal experience with freshwater flooding. Not all home buyers benefit from such well-informed or well-intentioned realtors and home buyers often navigate these complicated waters on their own. If in doubt, it’s better to be safe than sorry.

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace Michaels

[Street flooding from a heavy rain event in Jamie’s former South Florida neighborhood in October 2017. When drains are clogged by debris, streets easily flood with water creeping up driveways.]

I recently purchased a home in South Florida, and while going through the mortgage approval process, was informed that the home was outside of the high-risk area (aka the 100-year flood zone) and thus flood insurance wasn’t “required.” I’m also far enough inland to prevent storm surge (saltwater) inundation. However, the home is situated near a freshwater lake, and South Florida often experiences very heavy rains, sometimes exceeding 10 inches in a day. One can easily envision a scenario where debris, from heavy rains or winds, clogs the storm water drains and water pools in the street, eventually coming up the driveway and ultimately wetting the bottom floor of my home. Indeed, South Floridians are very accustomed to this very issue as it frequently occurs during our rainy season. Without flood insurance, I as the homeowner would be responsible for all the damage, which can easily climb into the thousands of dollars. Imagine replacing floors, walls, furniture, possessions, etc., and then taking steps to prevent mold. Given the small cost of flood insurance, the decision was an easy one and I determined that flood insurance was “needed” even if it wasn’t “required.” I was also lucky enough to have a realtor who was well-informed on flood insurance and overall flood risk. He encouraged the purchase of flood insurance citing his experience living in Florida and personal experience with freshwater flooding. Not all home buyers benefit from such well-informed or well-intentioned realtors and home buyers often navigate these complicated waters on their own. If in doubt, it’s better to be safe than sorry.

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace MichaelsAll Weather News

More