NOAA’s Polar Partner Satellite Is Launching in November

Special Stories

31 Oct 2018 11:20 AM

[EUMETSAT]

[NOAA] A new European weather satellite launching in November 2018 will provide the next-generation of data we depend on to predict Earth’s weather and climate.

On November 6, 2018, the European Organisation for the Exploitation of Meteorological Satellites (EUMETSAT) will launch Metop-C, a new polar-orbiting satellite that will collect valuable data about Earth’s atmosphere, land, and oceans used for daily weather forecasts around the globe.

A joint effort between EUMETSAT, the European Space Agency, NASA, and NOAA, Metop-C is the third satellite in the EUMETSAT Polar System series, which started with the launch of Metop-A in 2006, followed by Metop-B in 2012. Here are four reasons why we’re paying attention to Metop-C:

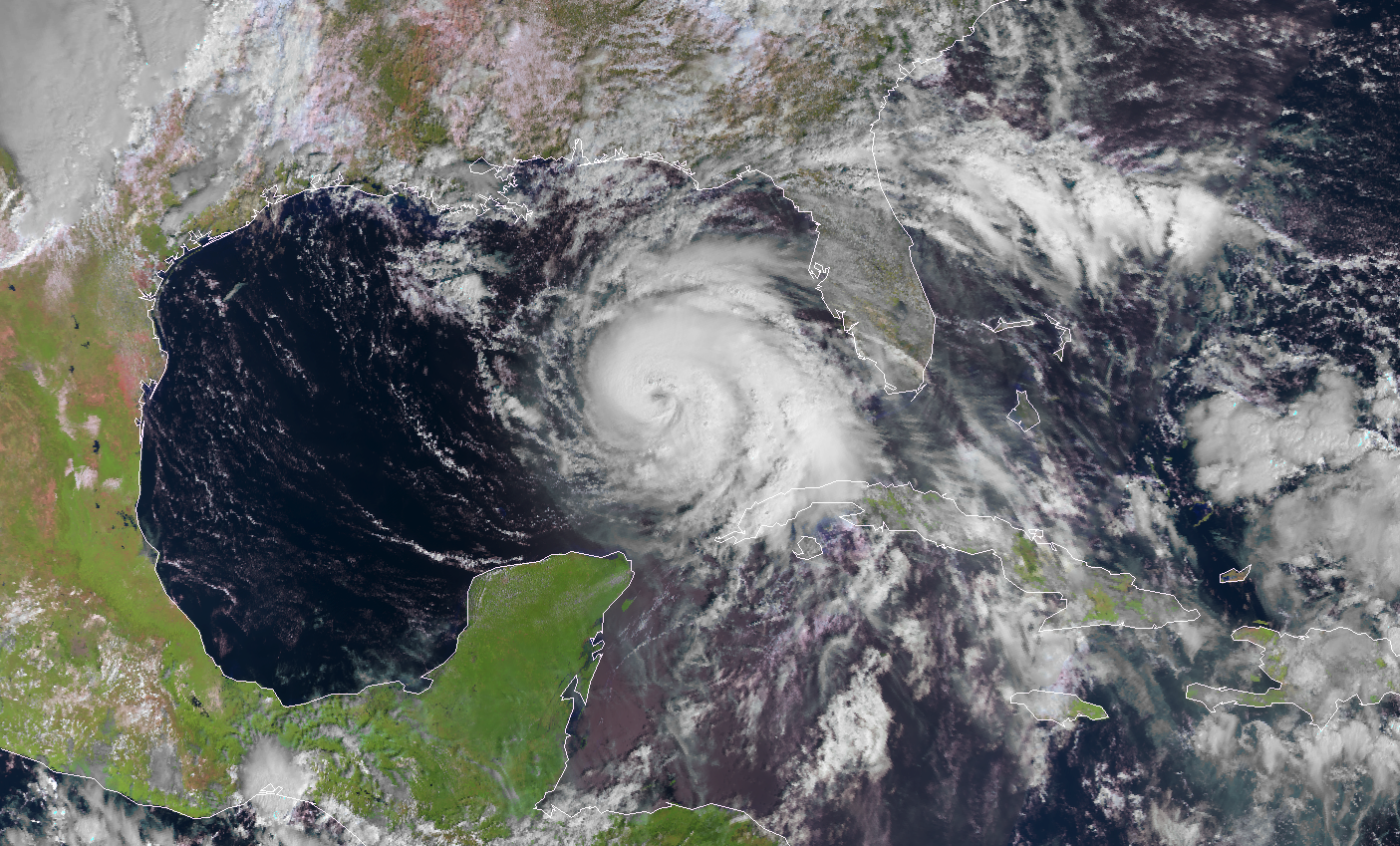

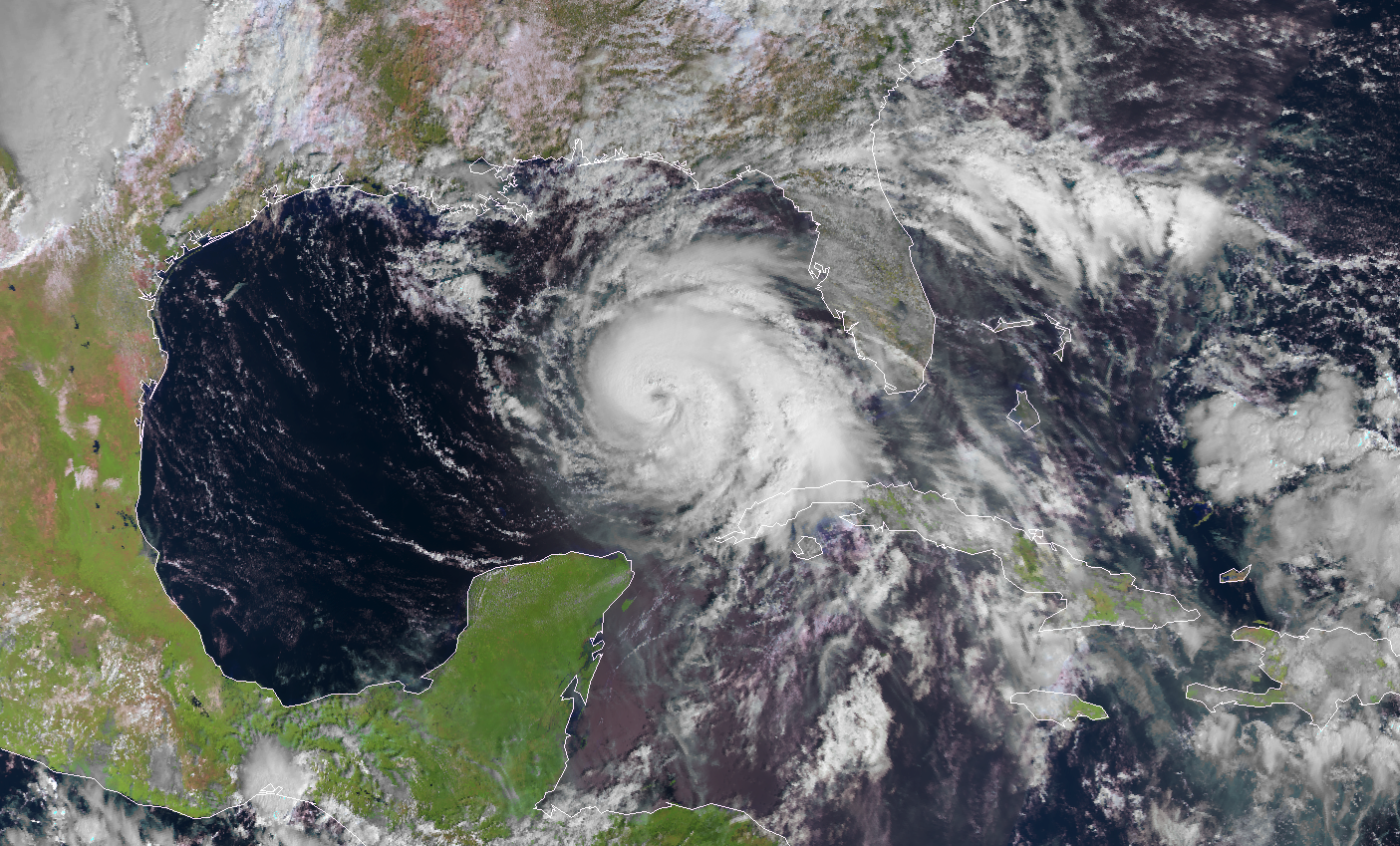

[Category 4 Hurricane Michael, seen from the Metop-A polar-orbiting satellite on Oct. 10, 2018. Credit: EUMETSAT]

[Category 4 Hurricane Michael, seen from the Metop-A polar-orbiting satellite on Oct. 10, 2018. Credit: EUMETSAT]

[Metop satellite from ESA]

[Metop satellite from ESA]

[Credit: CC0 Public Domain]

[Credit: CC0 Public Domain]

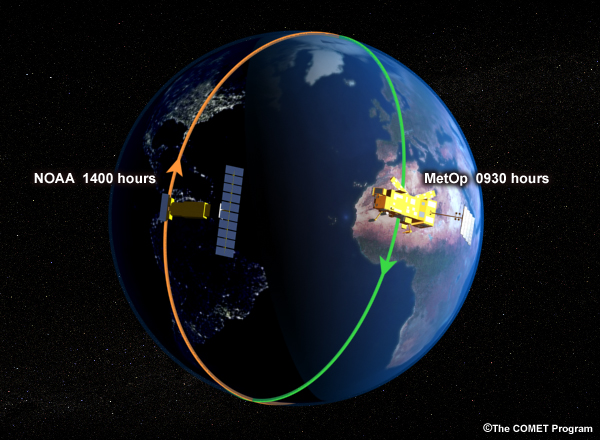

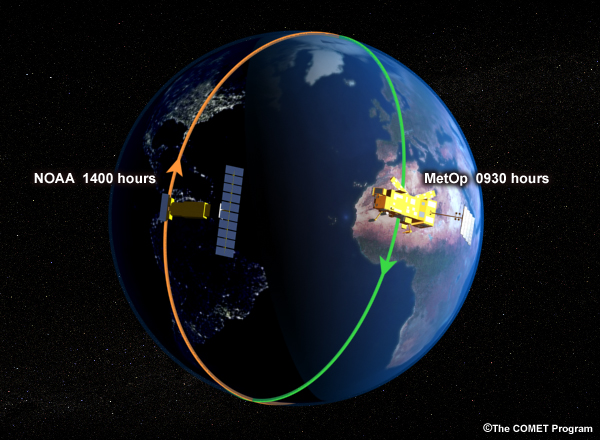

[NOAA and EUMETSAT polar-orbiting satellites pass over the same location at different times of

day. Credit: UCAR/COMET Program]

[NOAA and EUMETSAT polar-orbiting satellites pass over the same location at different times of

day. Credit: UCAR/COMET Program]

[MetOp-A from ESA]

After Metop-C is successfully launched from French Guiana on November 6, 2018 and has successfully completed its checkout period, it will replace Metop-B as the prime satellite of the Metop constellation. With Metop-A set to be decommissioned by early 2022, NOAA and EUMETSAT are planning for the next generation of Metop satellites (the EUMETSAT Polar System follow-on system), starting with Metop-SG 1A due to launch in 2021.

More information on the Metop satellites and the EPS-SG program is available on the EUMETSAT website.

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace Michaels

[MetOp-A from ESA]

After Metop-C is successfully launched from French Guiana on November 6, 2018 and has successfully completed its checkout period, it will replace Metop-B as the prime satellite of the Metop constellation. With Metop-A set to be decommissioned by early 2022, NOAA and EUMETSAT are planning for the next generation of Metop satellites (the EUMETSAT Polar System follow-on system), starting with Metop-SG 1A due to launch in 2021.

More information on the Metop satellites and the EPS-SG program is available on the EUMETSAT website.

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace Michaels

[Category 4 Hurricane Michael, seen from the Metop-A polar-orbiting satellite on Oct. 10, 2018. Credit: EUMETSAT]

[Category 4 Hurricane Michael, seen from the Metop-A polar-orbiting satellite on Oct. 10, 2018. Credit: EUMETSAT]

Our weather forecasts depend on it

Polar-orbiting satellites, which zip around the Earth from pole to pole about 14 times each day, are the backbone of our weather forecasting system. These satellites provide the bulk of the observations needed to make our medium and long-range weather forecasting successful. In order to predict the weather, we need to know what’s happening in the atmosphere – not just locally but around the globe. A typhoon in Japan today may bring a cold air outbreak in the eastern U.S. or heavy rain in California several days from now. Polar-orbiting satellites provide observations such as atmospheric temperature, wind, pressure, humidity, and land and sea surface conditions that we use to generate more accurate local forecasts and warnings. In the United States, about 85 percent of the atmospheric data that goes into weather prediction models comes from polar-orbiting satellites such as NOAA-20 and EUMETSAT’s Metop satellites. It is largely because of increased satellite observations that we’ve dramatically improved our ability to predict the track of major storms or how much it will rain or snow. Twenty years ago, our confidence in the forecast extended out to only two days. Thanks to our robust network of polar satellites and improvements in numerical weather prediction, we can now predict the weather 3 to 7 days in advance with the same level of confidence. [Metop satellite from ESA]

[Metop satellite from ESA]

The current Metop satellites are aging

The first two Metop satellites have long outlived their 5-year lifespan. The original plan was for each new Metop satellite to replace its predecessor. However, their better-than-expected performance allowed the satellites to continue operating simultaneously, providing more frequent meteorological data that has benefited weather forecasting. When Metop-C is launched, three Metop satellites will circle the Earth in concert. This means they will be able to collect more information about what is happening in the atmosphere, which ultimately improves the quality of weather forecasts. “We’re excited to have the next Metop satellite coming on-board,” said James (Jim) Yoe, Chief Administrative Officer of the Joint Center for Satellite Data Assimilation, a multi-agency research center between NOAA, NASA and the U.S. Department of Defense. “Having a third Metop satellite in orbit doesn’t just provide backup. It also means more data and stability to our weather forecasting needs.” [Credit: CC0 Public Domain]

[Credit: CC0 Public Domain]

Metop-C will carry critical U.S. instruments

While the Metop satellites are operated by our international partners, NOAA has been closely involved in the planning and design of the mission. NOAA supplied four of the thirteen instruments that will be flying on Metop-C. Two microwave radiometers, called AMSU A1 and AMSU A2, will measure global atmospheric temperature and humidity in all weather conditions, as well as sea ice. A visible/infrared radiometer called AVHRR will deliver global visible and infrared imagery of clouds, oceans, ice, and land surfaces. A fourth instrument, the Space Environment Monitor (SEM), will monitor the space plasma and radiation environment around the spacecraft. NOAA’s engineers and scientists have been working with EUMETSAT to ensure that the instruments are working properly when Metop-C is ready to launch. Should anything go wrong, NOAA will provide anomaly support for up to five years after launch. [NOAA and EUMETSAT polar-orbiting satellites pass over the same location at different times of

day. Credit: UCAR/COMET Program]

[NOAA and EUMETSAT polar-orbiting satellites pass over the same location at different times of

day. Credit: UCAR/COMET Program]

It benefits the global community

The EUMETSAT Polar System is part of the Joint Polar System (JPS), a partnership between NOAA and EUMETSAT that began in 1998. To ensure continuity of data, the NOAA and EUMETSAT satellites fly over the same reference location at different times of day. The Metop satellites monitor the “mid-morning” orbit, while NOAA’s polar-orbiting satellites, NOAA-20 and Suomi NPP, provide observations in the “mid-afternoon” orbit. It takes about 100 minutes for these satellites to complete one full orbit around the Earth. As they pass near the North and South Pole once every 50 minutes, the polar satellites send data to ground stations at either Svalbard, Norway or McMurdo Station, Antarctica. The Joint Polar System benefits not only Europe and the U.S., but the entire global community. Data from the NOAA and Metop satellites provide crucial weather and atmospheric data that leads to more accurate forecasts, which helps save lives and protect property. [MetOp-A from ESA]

After Metop-C is successfully launched from French Guiana on November 6, 2018 and has successfully completed its checkout period, it will replace Metop-B as the prime satellite of the Metop constellation. With Metop-A set to be decommissioned by early 2022, NOAA and EUMETSAT are planning for the next generation of Metop satellites (the EUMETSAT Polar System follow-on system), starting with Metop-SG 1A due to launch in 2021.

More information on the Metop satellites and the EPS-SG program is available on the EUMETSAT website.

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace Michaels

[MetOp-A from ESA]

After Metop-C is successfully launched from French Guiana on November 6, 2018 and has successfully completed its checkout period, it will replace Metop-B as the prime satellite of the Metop constellation. With Metop-A set to be decommissioned by early 2022, NOAA and EUMETSAT are planning for the next generation of Metop satellites (the EUMETSAT Polar System follow-on system), starting with Metop-SG 1A due to launch in 2021.

More information on the Metop satellites and the EPS-SG program is available on the EUMETSAT website.

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace MichaelsAll Weather News

More