Pacific Ocean Waters Under an El Niño Watch

Special Stories

15 Jun 2018 10:03 AM

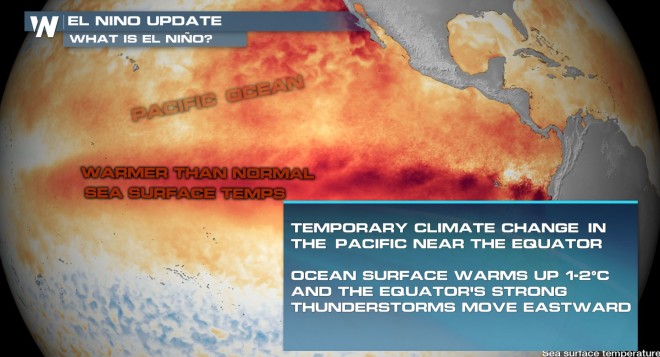

[May 2018 sea surface temperature departure from the 1981-2010 average. Graphic by NOAA climate; data from NOAA’s Environmental Visualization Lab.]

From NOAA by Emily Becker

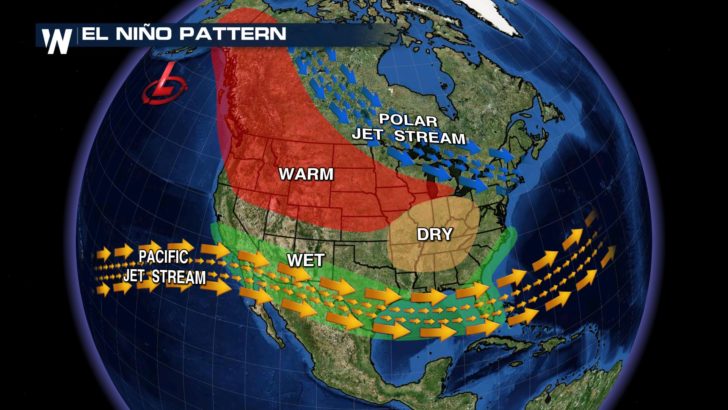

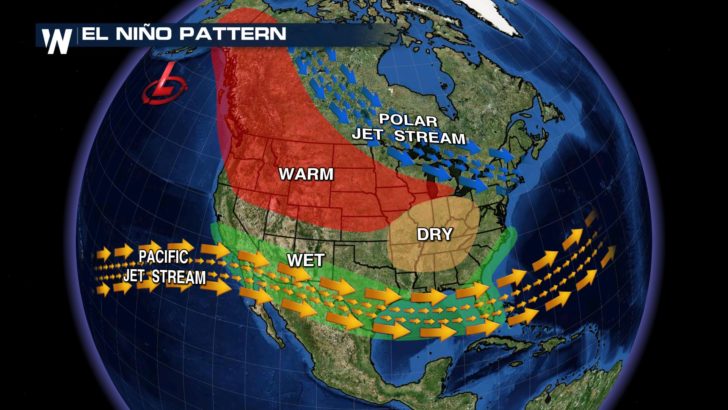

Well, well, well… what have we here? Favorable conditions for El Niño to develop? The June ENSO forecast estimates a 50% chance of El Niño developing during the late summer or early autumn, and an approximately 65% chance of El Niño conditions in the winter, so forecasters have instituted an El Niño Watch. Even last week in an article we published, signs are pointing toward an El Niño developing.

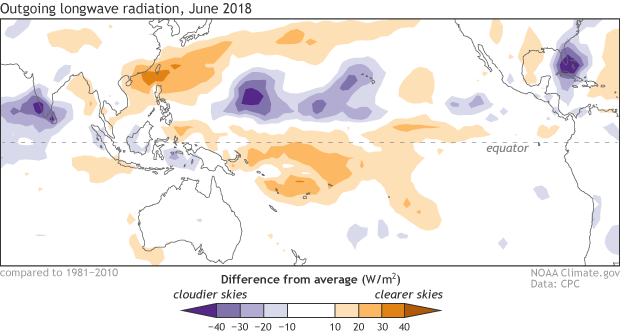

[Places that were more (purple) or less (orange) cloudy than the 1981-2010 average during May 2018, based on satellite observations of outgoing longwave radiation (heat). Thick clouds block heat from radiating out to space, so less radiation = more clouds, and more radiation = clearer skies. NOAA Climate map from CPC data.]

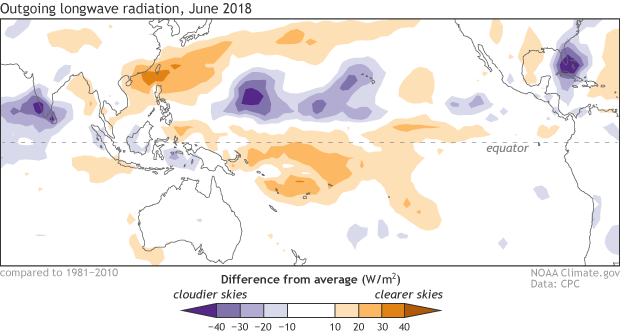

Some reduced cloudiness and rain remained over the central Pacific during May, but as we move into June, this pattern is weakening further.

[Places that were more (purple) or less (orange) cloudy than the 1981-2010 average during May 2018, based on satellite observations of outgoing longwave radiation (heat). Thick clouds block heat from radiating out to space, so less radiation = more clouds, and more radiation = clearer skies. NOAA Climate map from CPC data.]

Some reduced cloudiness and rain remained over the central Pacific during May, but as we move into June, this pattern is weakening further.

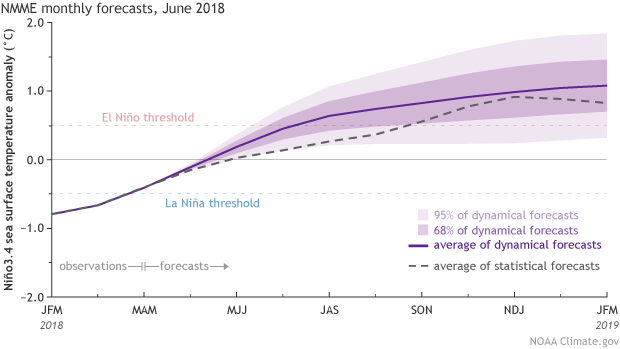

[Climate model forecasts for the Niño3.4 Index. Dynamical model data (purple line) from the North American Multi-Model Ensemble (NMME): darker purple envelope shows the range of 68% of all model forecasts; lighter purple shows the range of 95% of all model forecasts. Statistical model data (dashed line) from CPC’s Consolidated SST Forecasts. NOAA Climate image from CPC data.]

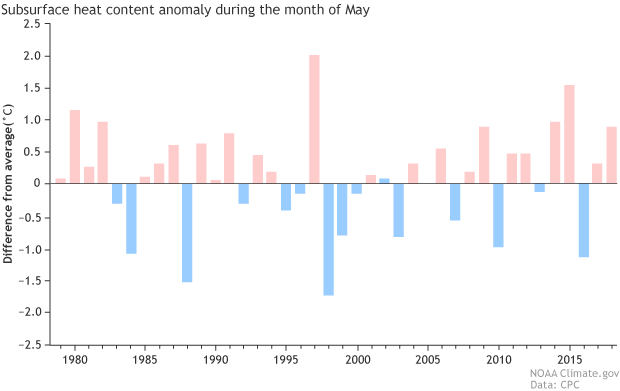

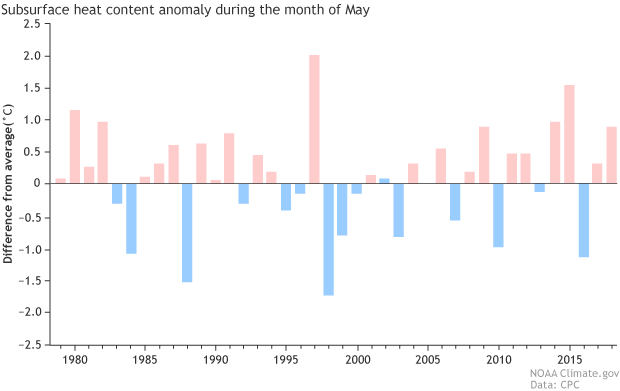

But wait, there’s more! The temperature of the water below the surface of the equatorial Pacific has been elevated since March, as a downwelling Kelvin wave formed and slowly moved from west to east under the surface. Recently, a second downwelling Kelvin wave reinforced the warmer-than-average subsurface conditions. The May 2018 subsurface heat content is about the 6th highest since 1979. You can read more about the recent warming in an article we published last week at this link.

[Climate model forecasts for the Niño3.4 Index. Dynamical model data (purple line) from the North American Multi-Model Ensemble (NMME): darker purple envelope shows the range of 68% of all model forecasts; lighter purple shows the range of 95% of all model forecasts. Statistical model data (dashed line) from CPC’s Consolidated SST Forecasts. NOAA Climate image from CPC data.]

But wait, there’s more! The temperature of the water below the surface of the equatorial Pacific has been elevated since March, as a downwelling Kelvin wave formed and slowly moved from west to east under the surface. Recently, a second downwelling Kelvin wave reinforced the warmer-than-average subsurface conditions. The May 2018 subsurface heat content is about the 6th highest since 1979. You can read more about the recent warming in an article we published last week at this link.

We care about the subsurface because it can provide a supply of warm water to the surface. As a downwelling Kelvin wave moves to the eastern part of the Pacific, the warmer waters will rise to the surface. Thus, elevated subsurface temperatures are often an early indicator that El Niño is on the way.

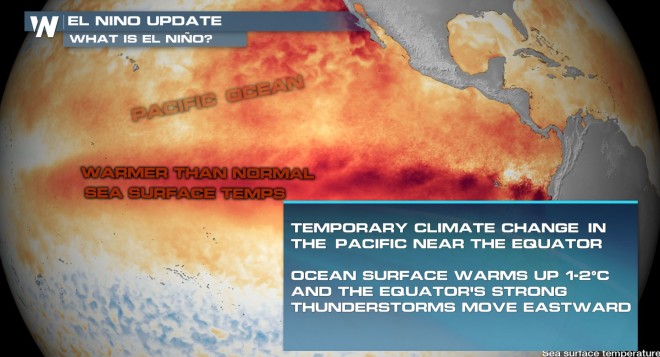

The positive phase of the Pacific Meridional Mode (visible in the north-south warm-cool pattern from the sea surface temperature map above) can also be an early indicator that conditions are favorable for El Niño to develop. This pattern can encourage the trade winds (the near-surface east-to-west winds along the equator) in the central Pacific to relax. The trade winds ordinarily serve to cool the surface and keep warmer waters “piled up” in the far western Pacific. Often, relaxed trade winds lead to downwelling Kelvin waves, as the warmer western waters are allowed to slosh eastward.

Speaking of relaxing trade winds… as we go to press, the trade winds in the eastern tropical Pacific have weakened as a “westerly wind burst” is taking place. (The effect of the Pacific Meridional Mode is usually farther to the west, and attributing the cause of any particular wind burst can be a difficult chicken-and-egg problem.) This westerly wind burst could work to enhance warming conditions.

We care about the subsurface because it can provide a supply of warm water to the surface. As a downwelling Kelvin wave moves to the eastern part of the Pacific, the warmer waters will rise to the surface. Thus, elevated subsurface temperatures are often an early indicator that El Niño is on the way.

The positive phase of the Pacific Meridional Mode (visible in the north-south warm-cool pattern from the sea surface temperature map above) can also be an early indicator that conditions are favorable for El Niño to develop. This pattern can encourage the trade winds (the near-surface east-to-west winds along the equator) in the central Pacific to relax. The trade winds ordinarily serve to cool the surface and keep warmer waters “piled up” in the far western Pacific. Often, relaxed trade winds lead to downwelling Kelvin waves, as the warmer western waters are allowed to slosh eastward.

Speaking of relaxing trade winds… as we go to press, the trade winds in the eastern tropical Pacific have weakened as a “westerly wind burst” is taking place. (The effect of the Pacific Meridional Mode is usually farther to the west, and attributing the cause of any particular wind burst can be a difficult chicken-and-egg problem.) This westerly wind burst could work to enhance warming conditions.

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace Michaels

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace Michaels

Who’s on first

Before we get into the potential for El Niño, let’s talk about right now. We are in neutral, and forecasters expect that ENSO-neutral conditions will play on through the summer. The surface temperature of the tropical Pacific Ocean is close to the long-term average in most areas, including the Niño3.4 region (our primary monitoring region for El Nino and La Nina), which was smack-dab on the average in the latest weekly measurement. Another interesting thing this map shows us is the prominent pattern of warmer-than-average surface temperatures north of the equator, and cooler-than-average waters south of the equator. This illustrates the strongly positive phase of the Pacific Meridional Mode… which I’ll get to in a minute. The atmosphere is also looking pretty ENSO-neutral. Remember, warmer-than-average waters tend to evaporate more water and warm the air above them, creating more rising motion and clouds than average. Cooler waters are the reverse, resulting in less cloud cover than average. During a La Niña event such as this past winter, we expect fewer clouds over the central Pacific, and more over Indonesia, which demonstrates the atmospheric response to La Niña’s cooler-than-average central Pacific. [Places that were more (purple) or less (orange) cloudy than the 1981-2010 average during May 2018, based on satellite observations of outgoing longwave radiation (heat). Thick clouds block heat from radiating out to space, so less radiation = more clouds, and more radiation = clearer skies. NOAA Climate map from CPC data.]

Some reduced cloudiness and rain remained over the central Pacific during May, but as we move into June, this pattern is weakening further.

[Places that were more (purple) or less (orange) cloudy than the 1981-2010 average during May 2018, based on satellite observations of outgoing longwave radiation (heat). Thick clouds block heat from radiating out to space, so less radiation = more clouds, and more radiation = clearer skies. NOAA Climate map from CPC data.]

Some reduced cloudiness and rain remained over the central Pacific during May, but as we move into June, this pattern is weakening further.

What’s on second

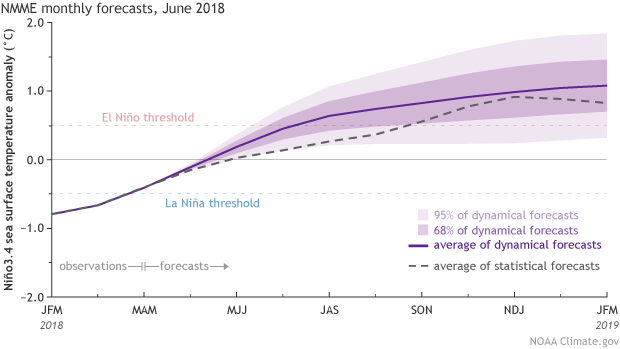

Computer model forecasts made in June are usually more reliable than those made earlier in the spring, thanks to the progression beyond the spring predictability barrier. While many of these models have been hinting at warming east-central Pacific sea surface temperatures for a few months, we can trust their predictions a bit more now that we’re moving past the spring barrier. Most of the dynamical models predict sea surface temperatures in the tropical Pacific will be more than 0.5°C warmer than the long-term average by this fall—i.e., above the threshold for El Niño conditions. Several statistical models, which make predictions by applying statistics to historical conditions, are also currently predicting sea surface temperatures in the El Niño realm by late fall. These models are often more conservative than the dynamical models, and the fact that both sets are largely in agreement is lending forecasters some confidence. [Climate model forecasts for the Niño3.4 Index. Dynamical model data (purple line) from the North American Multi-Model Ensemble (NMME): darker purple envelope shows the range of 68% of all model forecasts; lighter purple shows the range of 95% of all model forecasts. Statistical model data (dashed line) from CPC’s Consolidated SST Forecasts. NOAA Climate image from CPC data.]

But wait, there’s more! The temperature of the water below the surface of the equatorial Pacific has been elevated since March, as a downwelling Kelvin wave formed and slowly moved from west to east under the surface. Recently, a second downwelling Kelvin wave reinforced the warmer-than-average subsurface conditions. The May 2018 subsurface heat content is about the 6th highest since 1979. You can read more about the recent warming in an article we published last week at this link.

[Climate model forecasts for the Niño3.4 Index. Dynamical model data (purple line) from the North American Multi-Model Ensemble (NMME): darker purple envelope shows the range of 68% of all model forecasts; lighter purple shows the range of 95% of all model forecasts. Statistical model data (dashed line) from CPC’s Consolidated SST Forecasts. NOAA Climate image from CPC data.]

But wait, there’s more! The temperature of the water below the surface of the equatorial Pacific has been elevated since March, as a downwelling Kelvin wave formed and slowly moved from west to east under the surface. Recently, a second downwelling Kelvin wave reinforced the warmer-than-average subsurface conditions. The May 2018 subsurface heat content is about the 6th highest since 1979. You can read more about the recent warming in an article we published last week at this link.

[Area-averaged upper-ocean heat content anomaly (°C) in the equatorial Pacific (5°N-5°S, 180º-100ºW) during May. The heat content anomaly is computed as the departure from the 1981-2010 base period mean. NOAA Climate figure from CPC data.]

A note of caution’s on third

With all that said… it’s early yet. The winds along the equator are difficult to predict more than a week in advance, and as much as westerly wind bursts can help El Niño develop, so easterly wind bursts (when the trade winds strengthen) can discourage El Niño. Forecasters feel that current conditions are favorable for El Niño, so an El Niño Watch has been raised. We’ll keep a weather eye on those conditions as summer progresses. Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace Michaels

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace MichaelsAll Weather News

More