Predicting Midwest Corn Yield and Quality from Weather

Special Stories

18 Mar 2019 4:48 AM

[University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign] Corn is planted on approximately 90 million acres across the United States every year. With all that data, it takes months after harvest for government agencies to analyze total yield and grain quality. Scientists are working to shorten that timeline, making predictions for end-of-season yield by mid-season. However, fewer researchers have tackled predictions of grain quality, especially on large scales. A new University of Illinois study starts to fill that gap.

The study, published in Agronomy, uses a newly developed algorithm to predict both end-of-season yield and grain composition – the proportion of starch, oil, and protein in the kernel – by analyzing weather patterns during three important stages in corn development. Importantly, the predictions apply to the entire Midwest corn crop in the United States, regardless of corn genotypes or production practices.

“There are several studies assessing factors influencing quality for specific genotypes or specific locations, but before this study, we couldn’t make general predictions at this scale,” says Carrie Butts-Wilmsmeyer, research assistant professor in the Department of Crop Sciences at U of I and co-author of the study.

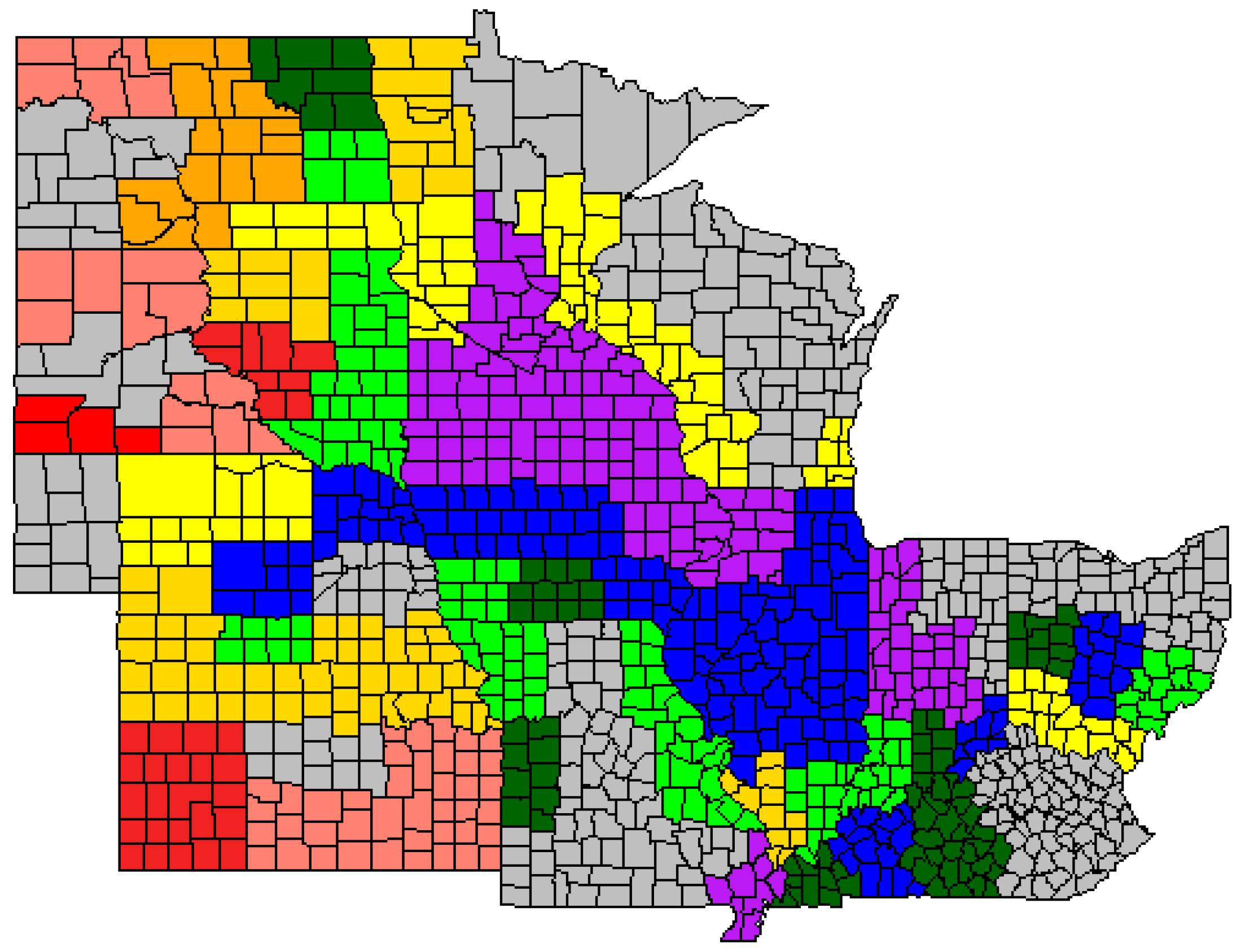

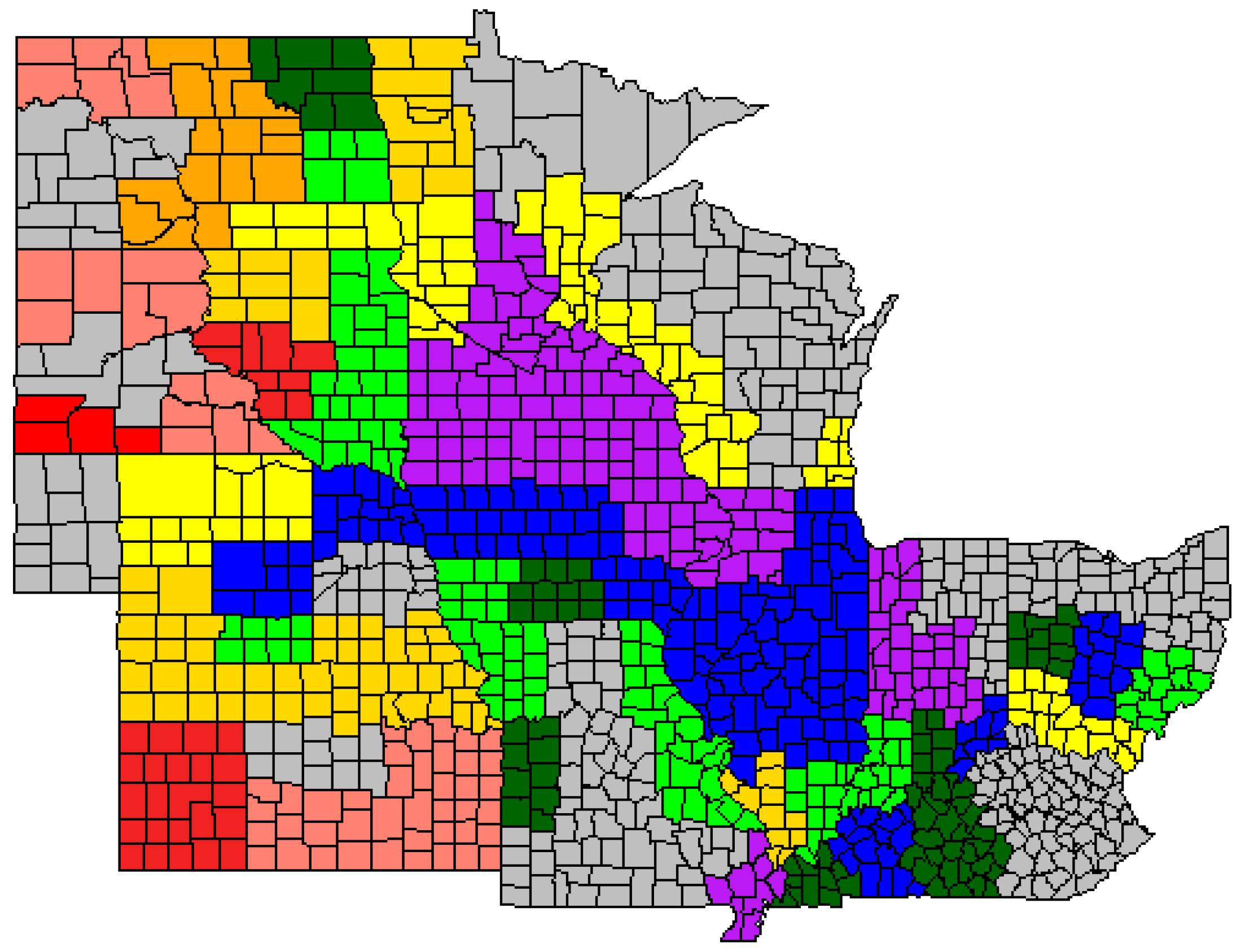

[Average corn grain quality across the Midwest, with red areas showing the highest-protein levels graduating to purple, showing the lowest protein but highest yields. Credit: Carrie Butts-Wilmsmeyer, University of Illinois]

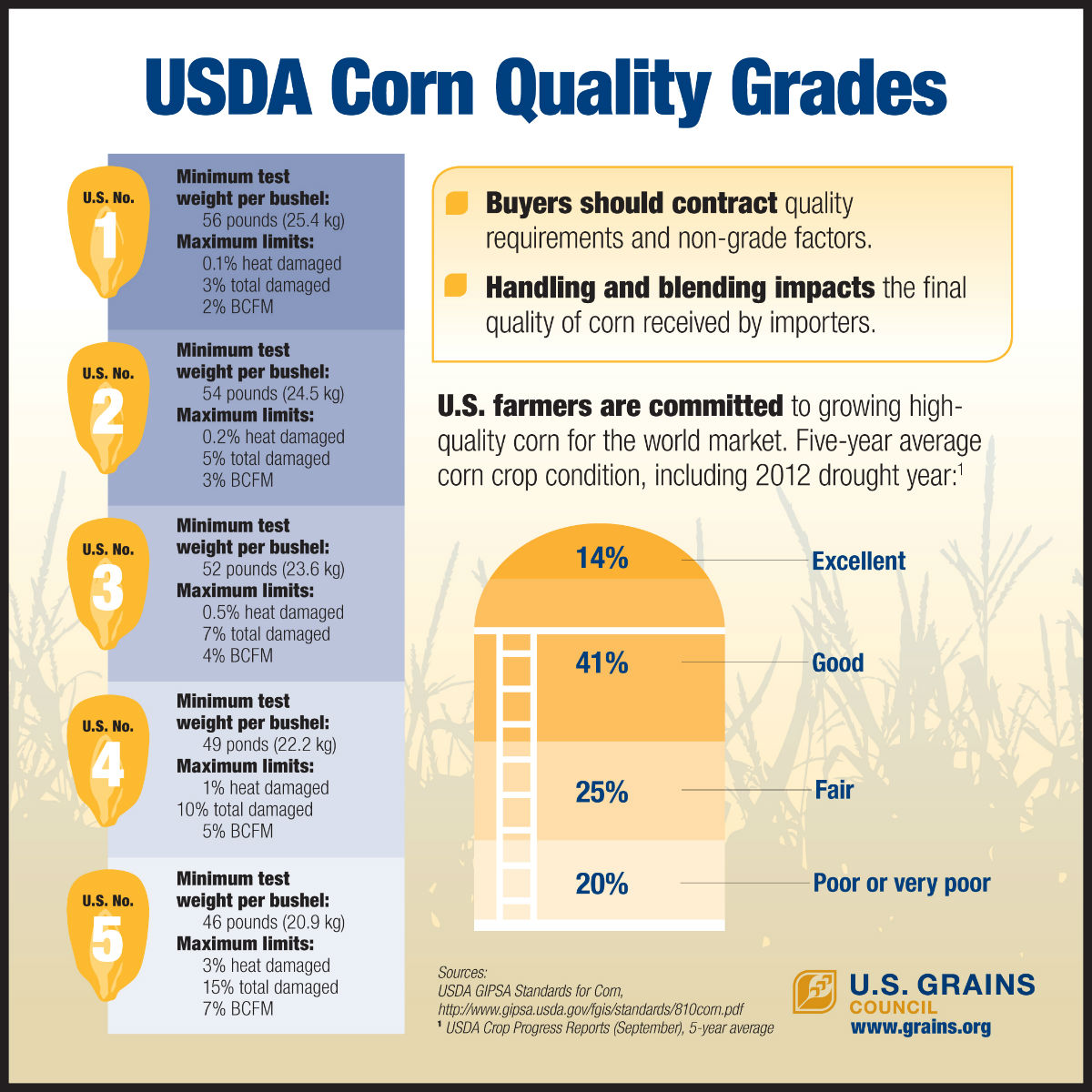

As corn arrives at elevators across the Midwest each season, the U.S. Grains Council takes samples to assess composition and quality for their annual summary reports, which are used for export sales. It was this comprehensive database that Butts-Wilmsmeyer and her colleagues used in developing their new algorithm.

“We used data from 2011 to 2017, which encompassed drought years as well as record-yielding years, and everything in between,” says Juliann Seebauer, principal research specialist in U of I’s Department of Crop Sciences and co-author of the study.

The researchers paired the grain-quality data with 2011- 2017 weather data from the regions feeding into each grain elevator. To build their algorithm, they concentrated on the weather during three critical periods – emergence, silking, and grain fill – and found that the strongest predictor of both grain yield and compositional quality was water availability during silking and grain fill.

[Average corn grain quality across the Midwest, with red areas showing the highest-protein levels graduating to purple, showing the lowest protein but highest yields. Credit: Carrie Butts-Wilmsmeyer, University of Illinois]

As corn arrives at elevators across the Midwest each season, the U.S. Grains Council takes samples to assess composition and quality for their annual summary reports, which are used for export sales. It was this comprehensive database that Butts-Wilmsmeyer and her colleagues used in developing their new algorithm.

“We used data from 2011 to 2017, which encompassed drought years as well as record-yielding years, and everything in between,” says Juliann Seebauer, principal research specialist in U of I’s Department of Crop Sciences and co-author of the study.

The researchers paired the grain-quality data with 2011- 2017 weather data from the regions feeding into each grain elevator. To build their algorithm, they concentrated on the weather during three critical periods – emergence, silking, and grain fill – and found that the strongest predictor of both grain yield and compositional quality was water availability during silking and grain fill.

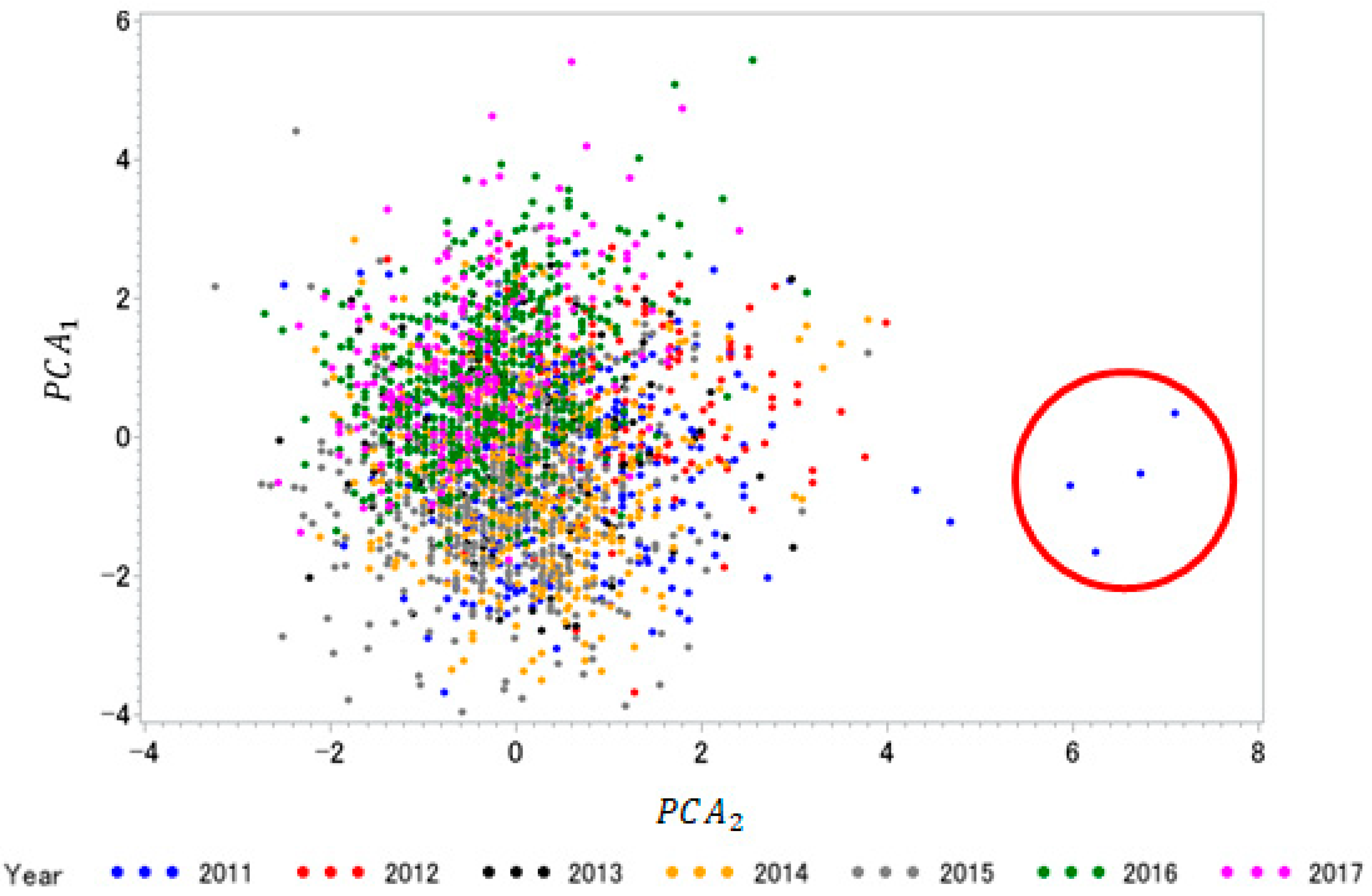

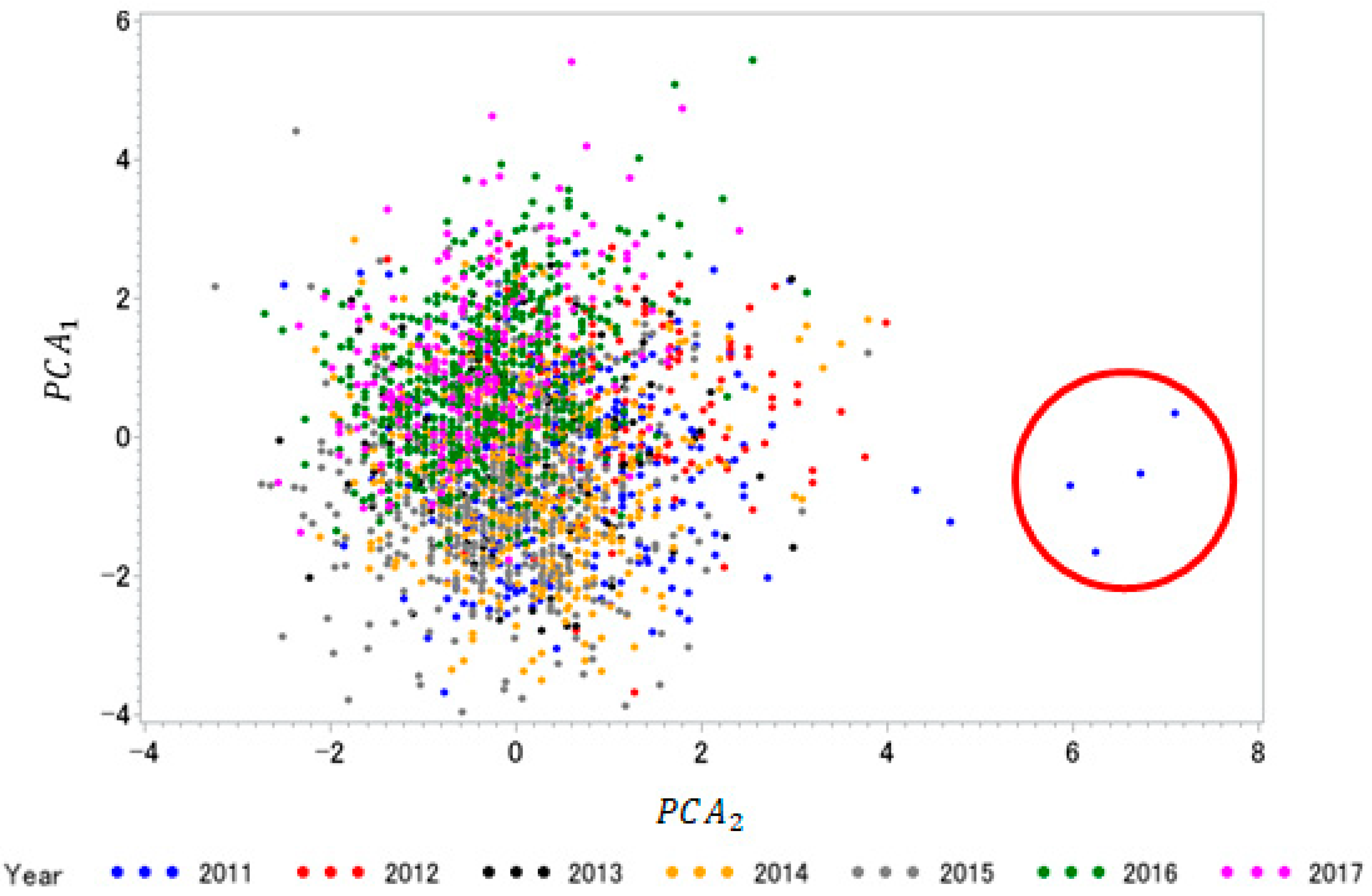

[Corn analysis by year. Different years are represented by different colors. Four outliers were identified for removal based on the analysis these being circled in red in the figure above. Years 2016 and 2017, represented by green and magenta points, respectively, were both high yielding years characterized by higher protein and oil concentrations. These two years separate from the other years in the plot, suggesting that these two analysis could be used to characterize improved compositional grain quality and yield simultaneously.]

The analysis went deeper, identifying conditions leading to higher oil or protein concentrations— information that matters to grain buyers.

The proportion of starch, oil, and protein in corn grain is influenced by genotype, soil nutrient availability, and weather. But the effect of weather isn’t always straightforward when it comes to protein. In drought conditions, stressed plants deposit less starch in the grain. Therefore, the grain has proportionally more protein than that of plants not experiencing drought stress. Good weather can also lead to higher protein concentrations. Plenty of water means more nitrogen is transported into the plant and incorporated into proteins.

In the analysis, “above-average grain protein and oil levels were favored by less nitrogen leaching during early vegetative growth, but also higher temperatures at flowering, while greater oil than protein concentrations resulted from lower temperatures during flowering and grain fill,” the authors say in the study.

[Corn analysis by year. Different years are represented by different colors. Four outliers were identified for removal based on the analysis these being circled in red in the figure above. Years 2016 and 2017, represented by green and magenta points, respectively, were both high yielding years characterized by higher protein and oil concentrations. These two years separate from the other years in the plot, suggesting that these two analysis could be used to characterize improved compositional grain quality and yield simultaneously.]

The analysis went deeper, identifying conditions leading to higher oil or protein concentrations— information that matters to grain buyers.

The proportion of starch, oil, and protein in corn grain is influenced by genotype, soil nutrient availability, and weather. But the effect of weather isn’t always straightforward when it comes to protein. In drought conditions, stressed plants deposit less starch in the grain. Therefore, the grain has proportionally more protein than that of plants not experiencing drought stress. Good weather can also lead to higher protein concentrations. Plenty of water means more nitrogen is transported into the plant and incorporated into proteins.

In the analysis, “above-average grain protein and oil levels were favored by less nitrogen leaching during early vegetative growth, but also higher temperatures at flowering, while greater oil than protein concentrations resulted from lower temperatures during flowering and grain fill,” the authors say in the study.

The ability to better predict protein and oil concentrations in grain could influence global markets, considering the growing domestic and international demand for higher-protein corn for animal feed applications. With the new algorithm, it should be theoretically possible to make end-of-season yield and quality predictions weeks or months ahead of harvest simply by looking at weather patterns.

“Other researchers have achieved real-time yield predictions using much more complex data and models. Ours was a comparatively simple approach, but we managed to add the quality piece and achieve decent accuracy,” Butts-Wilmsmeyer says. “The weather variables we found to be important in this study could be used in more complex analyses to achieve even greater accuracy in predicting both yield and quality in the future.”

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace Michaels

The ability to better predict protein and oil concentrations in grain could influence global markets, considering the growing domestic and international demand for higher-protein corn for animal feed applications. With the new algorithm, it should be theoretically possible to make end-of-season yield and quality predictions weeks or months ahead of harvest simply by looking at weather patterns.

“Other researchers have achieved real-time yield predictions using much more complex data and models. Ours was a comparatively simple approach, but we managed to add the quality piece and achieve decent accuracy,” Butts-Wilmsmeyer says. “The weather variables we found to be important in this study could be used in more complex analyses to achieve even greater accuracy in predicting both yield and quality in the future.”

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace Michaels

[Average corn grain quality across the Midwest, with red areas showing the highest-protein levels graduating to purple, showing the lowest protein but highest yields. Credit: Carrie Butts-Wilmsmeyer, University of Illinois]

As corn arrives at elevators across the Midwest each season, the U.S. Grains Council takes samples to assess composition and quality for their annual summary reports, which are used for export sales. It was this comprehensive database that Butts-Wilmsmeyer and her colleagues used in developing their new algorithm.

“We used data from 2011 to 2017, which encompassed drought years as well as record-yielding years, and everything in between,” says Juliann Seebauer, principal research specialist in U of I’s Department of Crop Sciences and co-author of the study.

The researchers paired the grain-quality data with 2011- 2017 weather data from the regions feeding into each grain elevator. To build their algorithm, they concentrated on the weather during three critical periods – emergence, silking, and grain fill – and found that the strongest predictor of both grain yield and compositional quality was water availability during silking and grain fill.

[Average corn grain quality across the Midwest, with red areas showing the highest-protein levels graduating to purple, showing the lowest protein but highest yields. Credit: Carrie Butts-Wilmsmeyer, University of Illinois]

As corn arrives at elevators across the Midwest each season, the U.S. Grains Council takes samples to assess composition and quality for their annual summary reports, which are used for export sales. It was this comprehensive database that Butts-Wilmsmeyer and her colleagues used in developing their new algorithm.

“We used data from 2011 to 2017, which encompassed drought years as well as record-yielding years, and everything in between,” says Juliann Seebauer, principal research specialist in U of I’s Department of Crop Sciences and co-author of the study.

The researchers paired the grain-quality data with 2011- 2017 weather data from the regions feeding into each grain elevator. To build their algorithm, they concentrated on the weather during three critical periods – emergence, silking, and grain fill – and found that the strongest predictor of both grain yield and compositional quality was water availability during silking and grain fill.

[Corn analysis by year. Different years are represented by different colors. Four outliers were identified for removal based on the analysis these being circled in red in the figure above. Years 2016 and 2017, represented by green and magenta points, respectively, were both high yielding years characterized by higher protein and oil concentrations. These two years separate from the other years in the plot, suggesting that these two analysis could be used to characterize improved compositional grain quality and yield simultaneously.]

The analysis went deeper, identifying conditions leading to higher oil or protein concentrations— information that matters to grain buyers.

The proportion of starch, oil, and protein in corn grain is influenced by genotype, soil nutrient availability, and weather. But the effect of weather isn’t always straightforward when it comes to protein. In drought conditions, stressed plants deposit less starch in the grain. Therefore, the grain has proportionally more protein than that of plants not experiencing drought stress. Good weather can also lead to higher protein concentrations. Plenty of water means more nitrogen is transported into the plant and incorporated into proteins.

In the analysis, “above-average grain protein and oil levels were favored by less nitrogen leaching during early vegetative growth, but also higher temperatures at flowering, while greater oil than protein concentrations resulted from lower temperatures during flowering and grain fill,” the authors say in the study.

[Corn analysis by year. Different years are represented by different colors. Four outliers were identified for removal based on the analysis these being circled in red in the figure above. Years 2016 and 2017, represented by green and magenta points, respectively, were both high yielding years characterized by higher protein and oil concentrations. These two years separate from the other years in the plot, suggesting that these two analysis could be used to characterize improved compositional grain quality and yield simultaneously.]

The analysis went deeper, identifying conditions leading to higher oil or protein concentrations— information that matters to grain buyers.

The proportion of starch, oil, and protein in corn grain is influenced by genotype, soil nutrient availability, and weather. But the effect of weather isn’t always straightforward when it comes to protein. In drought conditions, stressed plants deposit less starch in the grain. Therefore, the grain has proportionally more protein than that of plants not experiencing drought stress. Good weather can also lead to higher protein concentrations. Plenty of water means more nitrogen is transported into the plant and incorporated into proteins.

In the analysis, “above-average grain protein and oil levels were favored by less nitrogen leaching during early vegetative growth, but also higher temperatures at flowering, while greater oil than protein concentrations resulted from lower temperatures during flowering and grain fill,” the authors say in the study.

The ability to better predict protein and oil concentrations in grain could influence global markets, considering the growing domestic and international demand for higher-protein corn for animal feed applications. With the new algorithm, it should be theoretically possible to make end-of-season yield and quality predictions weeks or months ahead of harvest simply by looking at weather patterns.

“Other researchers have achieved real-time yield predictions using much more complex data and models. Ours was a comparatively simple approach, but we managed to add the quality piece and achieve decent accuracy,” Butts-Wilmsmeyer says. “The weather variables we found to be important in this study could be used in more complex analyses to achieve even greater accuracy in predicting both yield and quality in the future.”

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace Michaels

The ability to better predict protein and oil concentrations in grain could influence global markets, considering the growing domestic and international demand for higher-protein corn for animal feed applications. With the new algorithm, it should be theoretically possible to make end-of-season yield and quality predictions weeks or months ahead of harvest simply by looking at weather patterns.

“Other researchers have achieved real-time yield predictions using much more complex data and models. Ours was a comparatively simple approach, but we managed to add the quality piece and achieve decent accuracy,” Butts-Wilmsmeyer says. “The weather variables we found to be important in this study could be used in more complex analyses to achieve even greater accuracy in predicting both yield and quality in the future.”

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace MichaelsAll Weather News

More