Satellite Images Show Major Flooding Along Rivers in the Southeast U.S.

Special Stories

28 Feb 2019 9:31 AM

[NOAA] The severe storms that brought flooding, tornadoes, damaging winds, and hail to the Southeast over the weekend, leaving tens of thousands without power, were the result of a “meteorological battle zone” between warm and cold air, said Walt Zaleski, warning coordination meteorologist for NOAA’s National Weather Service Regional Headquarters in Fort Worth, Texas. A low-pressure system over the Southern Plains pushed warm, moist air from the Gulf of Mexico over the southeastern United States, while cold, drier air dropped from Canada into the Northern and Central Plains and the Midwest and Great Lakes regions.

The result was record rainfall that caused flooding in the Mississippi, Ohio and Tennessee River valleys, along with the Green and Wabash rivers in Kentucky and Indiana.

This convergence of cold and warm air “creates a traffic jam in the atmosphere, and the air has nowhere to go but up,” Zaleski said. “It’s like someone taking a sponge full of moisture, twisting it and wringing out all that moisture...It just sets up the perfect cycle of above-normal precipitation to fall over the Southeast United States.”

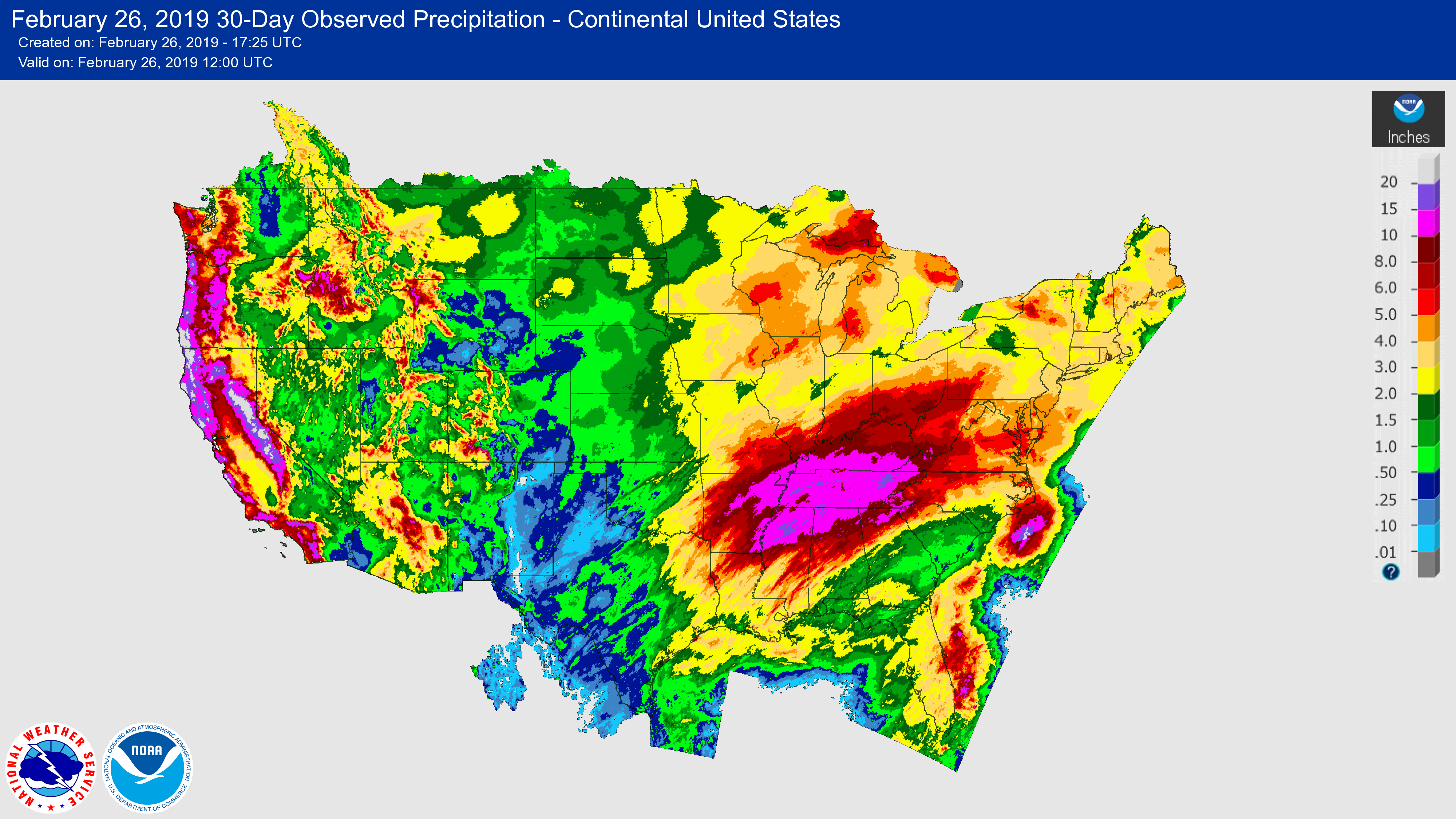

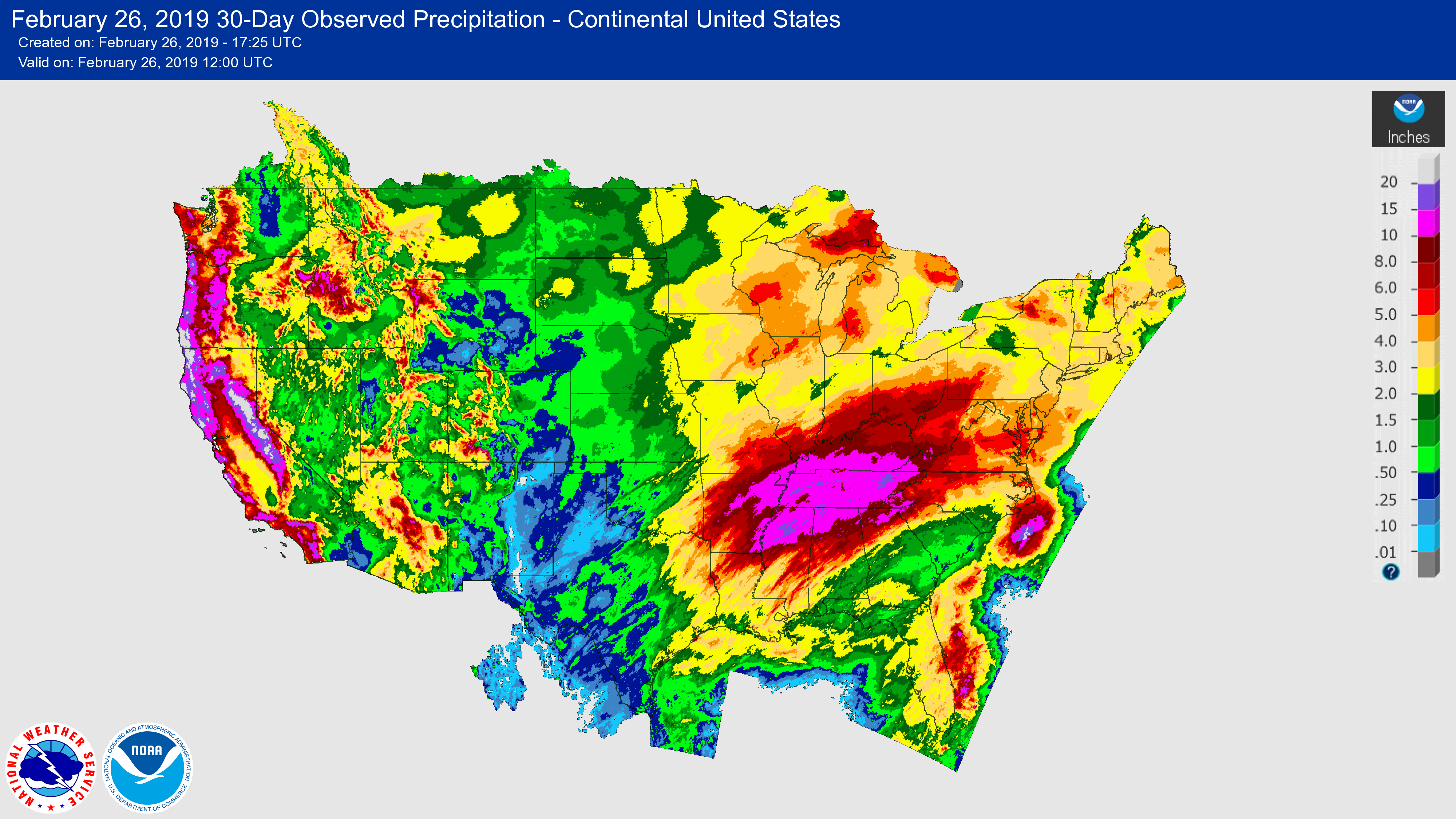

Over a 30-day period ending February 26, Tennessee, northern Alabama, northern Mississippi, eastern Arkansas and most of Kentucky received 10 to 15 inches of rain, five to eight inches above the normal amount of rainfall during that period, according to Zaleski.

The result was record rainfall that caused flooding in the Mississippi, Ohio and Tennessee River valleys, along with the Green and Wabash rivers in Kentucky and Indiana.

This convergence of cold and warm air “creates a traffic jam in the atmosphere, and the air has nowhere to go but up,” Zaleski said. “It’s like someone taking a sponge full of moisture, twisting it and wringing out all that moisture...It just sets up the perfect cycle of above-normal precipitation to fall over the Southeast United States.”

Over a 30-day period ending February 26, Tennessee, northern Alabama, northern Mississippi, eastern Arkansas and most of Kentucky received 10 to 15 inches of rain, five to eight inches above the normal amount of rainfall during that period, according to Zaleski.

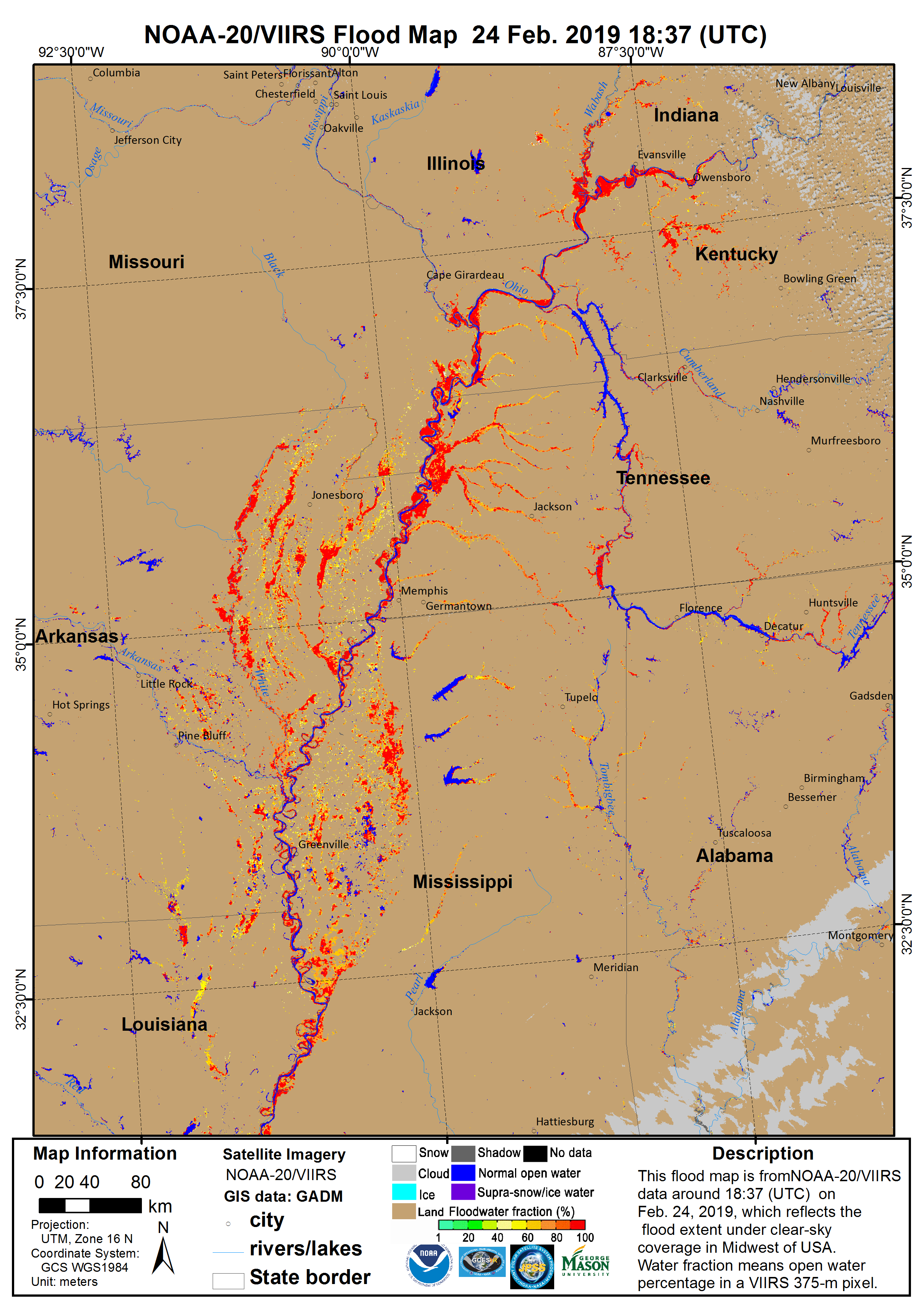

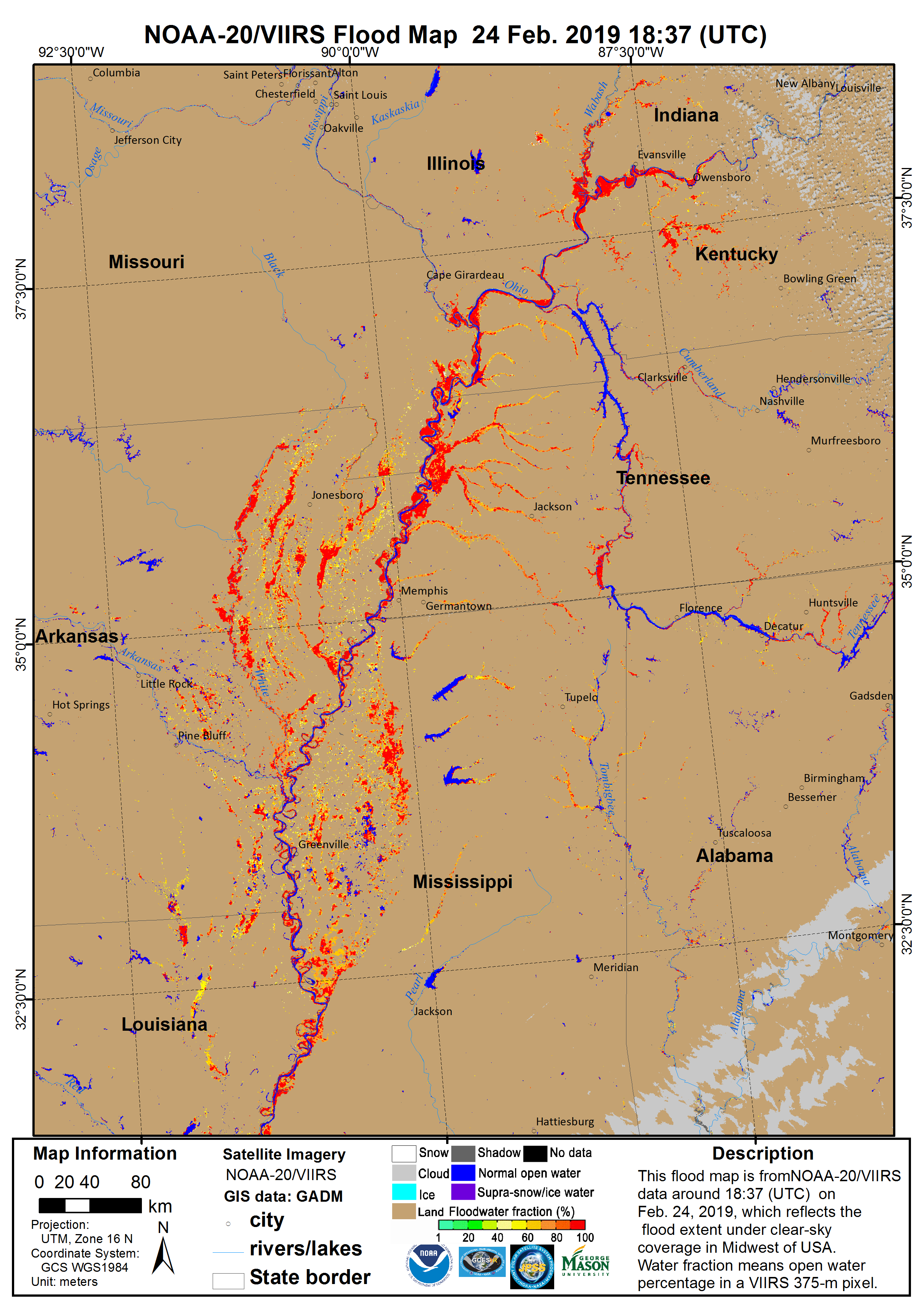

The flood map below, generated using images taken by the VIIRS instrument on the NOAA-20 satellite on Sunday afternoon, captures the scope of flooding in this region with blue showing normal water and red indicating the most severe flooding, said Dr. Sanmei Li, assistant research professor at George Mason University and one of the developers of the flood product.

Li has developed algorithms that can produce flood maps using visible, near-infrared and short-wave infrared channels from the polar-orbiting VIIRS instrument as well as the ABI sensor on the new NOAA GOES satellites.

The flood map below, generated using images taken by the VIIRS instrument on the NOAA-20 satellite on Sunday afternoon, captures the scope of flooding in this region with blue showing normal water and red indicating the most severe flooding, said Dr. Sanmei Li, assistant research professor at George Mason University and one of the developers of the flood product.

Li has developed algorithms that can produce flood maps using visible, near-infrared and short-wave infrared channels from the polar-orbiting VIIRS instrument as well as the ABI sensor on the new NOAA GOES satellites.

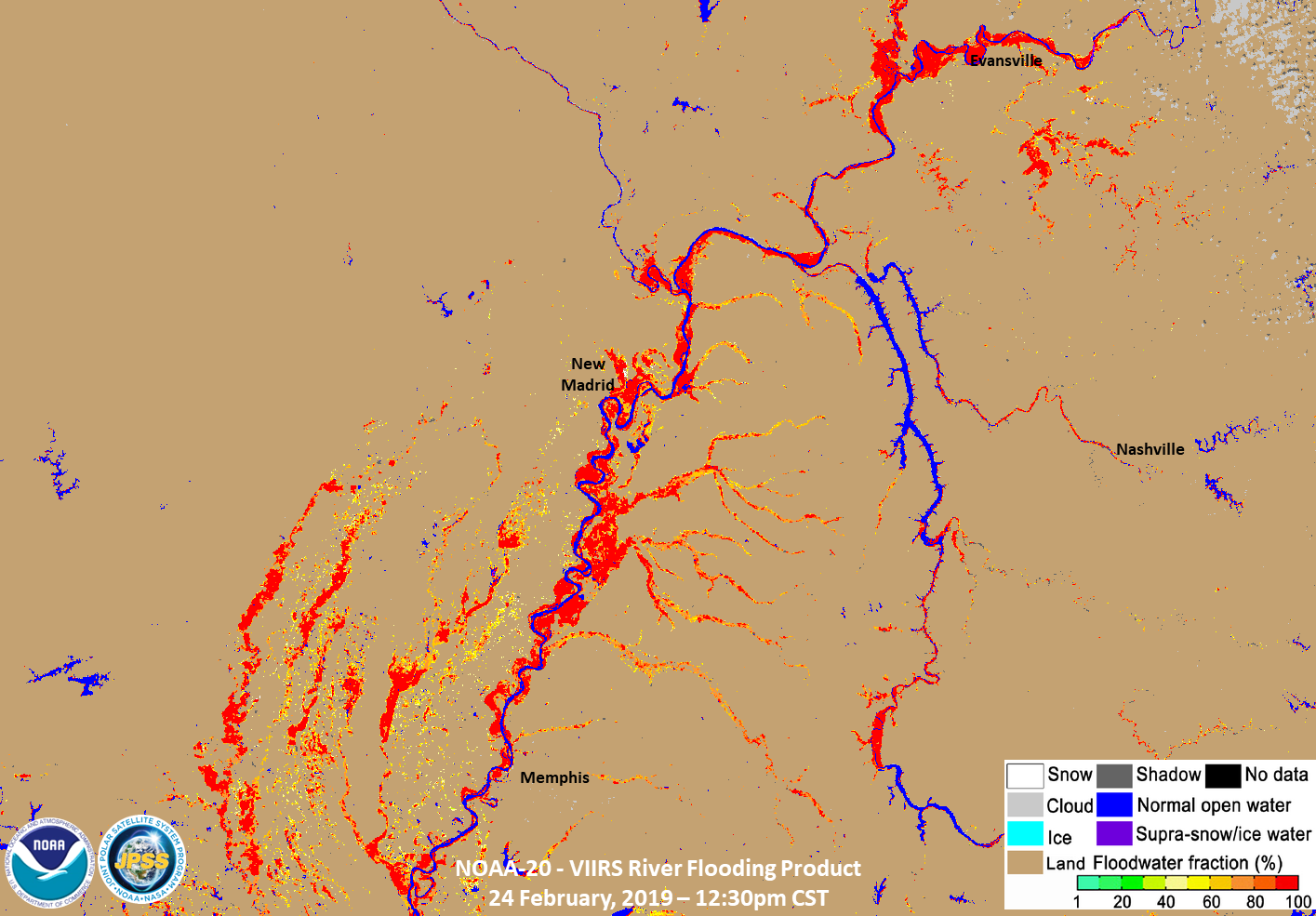

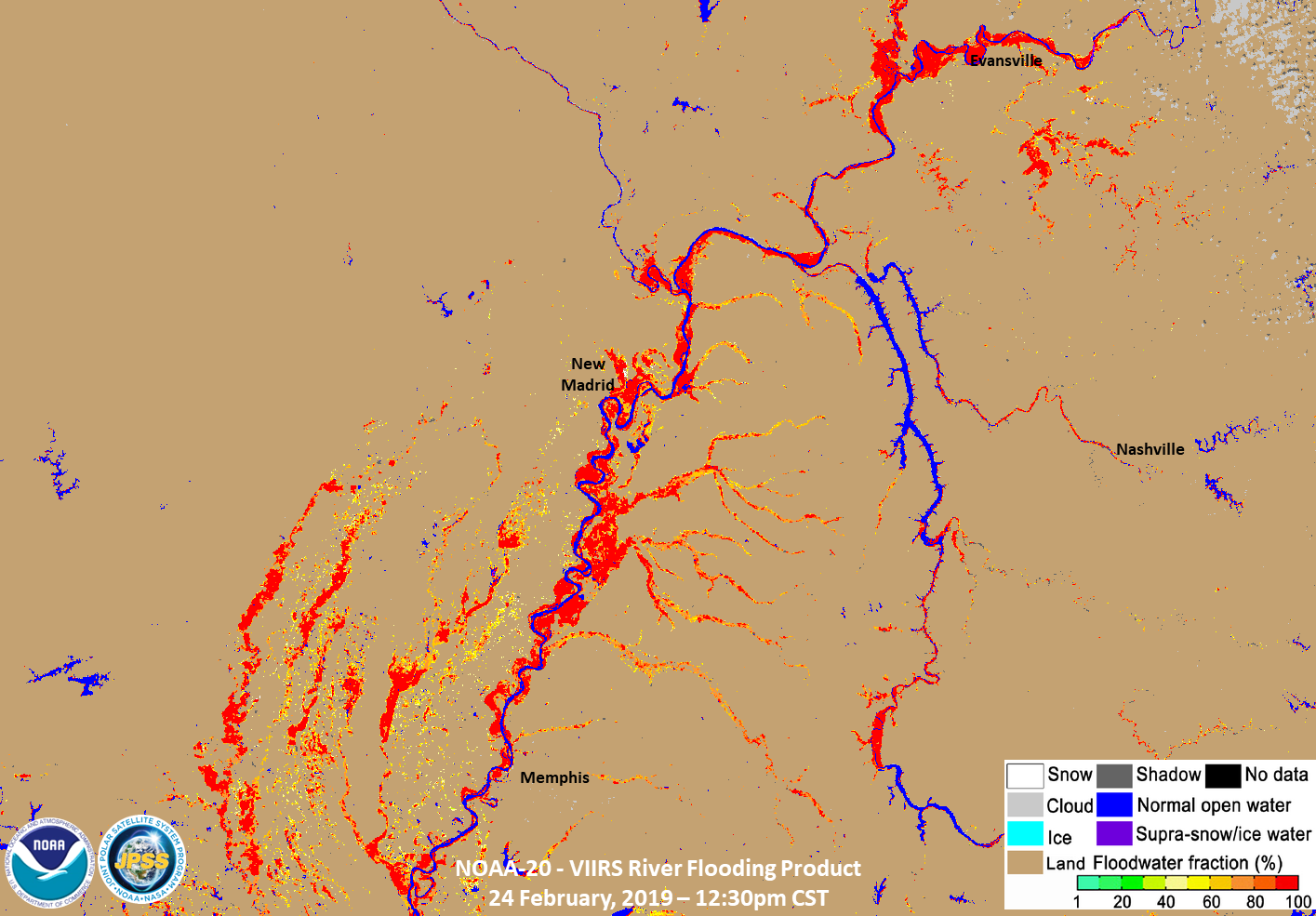

The image at the top of the page is a zoomed-in shot that shows flooding along the Mississippi, Ohio and Tennessee Rivers near Evansville, Indiana, New Madrid, Missouri, and Nashville. VIIRS provides high spatial resolution, which is especially important for forecast centers,” said William Straka III, researcher for the Cooperative Institute for Meteorological Satellite Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “You want to know what’s going on with the little creeks and rivers and streams, because people live along those.”

This NOAA-20 true color image shows the same region, as seen from space. You can see how it’s difficult, especially in winter when even the rivers look brown, to distinguish flooded areas.

The image at the top of the page is a zoomed-in shot that shows flooding along the Mississippi, Ohio and Tennessee Rivers near Evansville, Indiana, New Madrid, Missouri, and Nashville. VIIRS provides high spatial resolution, which is especially important for forecast centers,” said William Straka III, researcher for the Cooperative Institute for Meteorological Satellite Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “You want to know what’s going on with the little creeks and rivers and streams, because people live along those.”

This NOAA-20 true color image shows the same region, as seen from space. You can see how it’s difficult, especially in winter when even the rivers look brown, to distinguish flooded areas.

“This is why you need to have the algorithm to pull out that information and translate it into a product that can be used by the forecasters and emergency managers,” Straka said. “They can use these to issue warnings and say, ‘There’s lots of flooding over here, but not so much over here. Let’s direct the resources to people who really need it.’”

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace Michaels

“This is why you need to have the algorithm to pull out that information and translate it into a product that can be used by the forecasters and emergency managers,” Straka said. “They can use these to issue warnings and say, ‘There’s lots of flooding over here, but not so much over here. Let’s direct the resources to people who really need it.’”

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace Michaels

The result was record rainfall that caused flooding in the Mississippi, Ohio and Tennessee River valleys, along with the Green and Wabash rivers in Kentucky and Indiana.

This convergence of cold and warm air “creates a traffic jam in the atmosphere, and the air has nowhere to go but up,” Zaleski said. “It’s like someone taking a sponge full of moisture, twisting it and wringing out all that moisture...It just sets up the perfect cycle of above-normal precipitation to fall over the Southeast United States.”

Over a 30-day period ending February 26, Tennessee, northern Alabama, northern Mississippi, eastern Arkansas and most of Kentucky received 10 to 15 inches of rain, five to eight inches above the normal amount of rainfall during that period, according to Zaleski.

The result was record rainfall that caused flooding in the Mississippi, Ohio and Tennessee River valleys, along with the Green and Wabash rivers in Kentucky and Indiana.

This convergence of cold and warm air “creates a traffic jam in the atmosphere, and the air has nowhere to go but up,” Zaleski said. “It’s like someone taking a sponge full of moisture, twisting it and wringing out all that moisture...It just sets up the perfect cycle of above-normal precipitation to fall over the Southeast United States.”

Over a 30-day period ending February 26, Tennessee, northern Alabama, northern Mississippi, eastern Arkansas and most of Kentucky received 10 to 15 inches of rain, five to eight inches above the normal amount of rainfall during that period, according to Zaleski.

The flood map below, generated using images taken by the VIIRS instrument on the NOAA-20 satellite on Sunday afternoon, captures the scope of flooding in this region with blue showing normal water and red indicating the most severe flooding, said Dr. Sanmei Li, assistant research professor at George Mason University and one of the developers of the flood product.

Li has developed algorithms that can produce flood maps using visible, near-infrared and short-wave infrared channels from the polar-orbiting VIIRS instrument as well as the ABI sensor on the new NOAA GOES satellites.

The flood map below, generated using images taken by the VIIRS instrument on the NOAA-20 satellite on Sunday afternoon, captures the scope of flooding in this region with blue showing normal water and red indicating the most severe flooding, said Dr. Sanmei Li, assistant research professor at George Mason University and one of the developers of the flood product.

Li has developed algorithms that can produce flood maps using visible, near-infrared and short-wave infrared channels from the polar-orbiting VIIRS instrument as well as the ABI sensor on the new NOAA GOES satellites.

The image at the top of the page is a zoomed-in shot that shows flooding along the Mississippi, Ohio and Tennessee Rivers near Evansville, Indiana, New Madrid, Missouri, and Nashville. VIIRS provides high spatial resolution, which is especially important for forecast centers,” said William Straka III, researcher for the Cooperative Institute for Meteorological Satellite Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “You want to know what’s going on with the little creeks and rivers and streams, because people live along those.”

This NOAA-20 true color image shows the same region, as seen from space. You can see how it’s difficult, especially in winter when even the rivers look brown, to distinguish flooded areas.

The image at the top of the page is a zoomed-in shot that shows flooding along the Mississippi, Ohio and Tennessee Rivers near Evansville, Indiana, New Madrid, Missouri, and Nashville. VIIRS provides high spatial resolution, which is especially important for forecast centers,” said William Straka III, researcher for the Cooperative Institute for Meteorological Satellite Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “You want to know what’s going on with the little creeks and rivers and streams, because people live along those.”

This NOAA-20 true color image shows the same region, as seen from space. You can see how it’s difficult, especially in winter when even the rivers look brown, to distinguish flooded areas.

“This is why you need to have the algorithm to pull out that information and translate it into a product that can be used by the forecasters and emergency managers,” Straka said. “They can use these to issue warnings and say, ‘There’s lots of flooding over here, but not so much over here. Let’s direct the resources to people who really need it.’”

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace Michaels

“This is why you need to have the algorithm to pull out that information and translate it into a product that can be used by the forecasters and emergency managers,” Straka said. “They can use these to issue warnings and say, ‘There’s lots of flooding over here, but not so much over here. Let’s direct the resources to people who really need it.’”

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace MichaelsAll Weather News

More