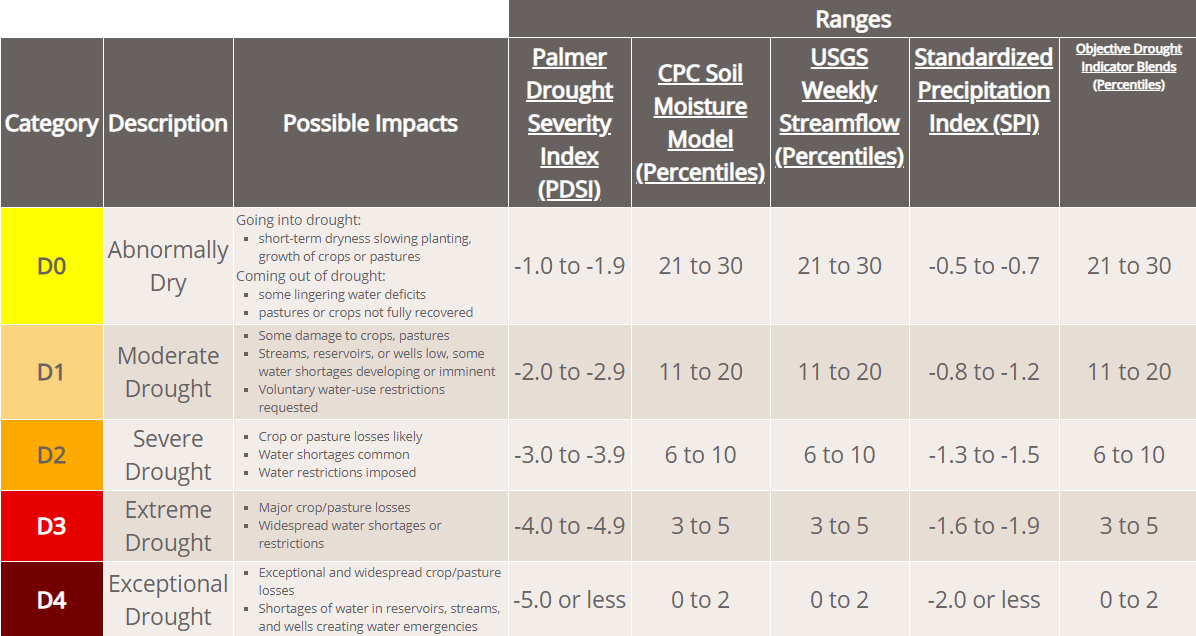

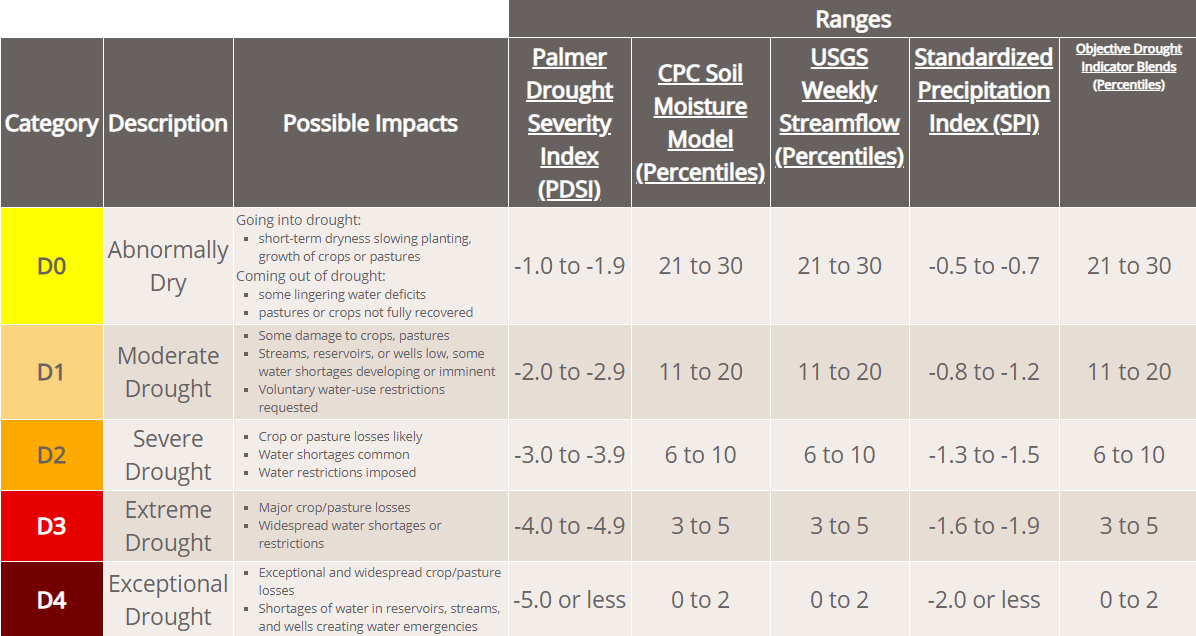

The categories depict how rare the drought intensity is. A D1 drought, for example, occurs on average 11%–20% of the time in the historical record—that is, in the range of once every 5–10 years. A D4 drought occurs on average up to 2% of the time, meaning once every 50 years or even less frequently.

Data are collected through 8 a.m. ET Tuesday, and the new maps are released on Thursday. A lot of work happens in that compressed time frame because the map is not the simple output of a statistical model. Instead, it draws on a broad range of numerical data as well as input from local observers, all filtered through the seasoned judgment of drought experts.

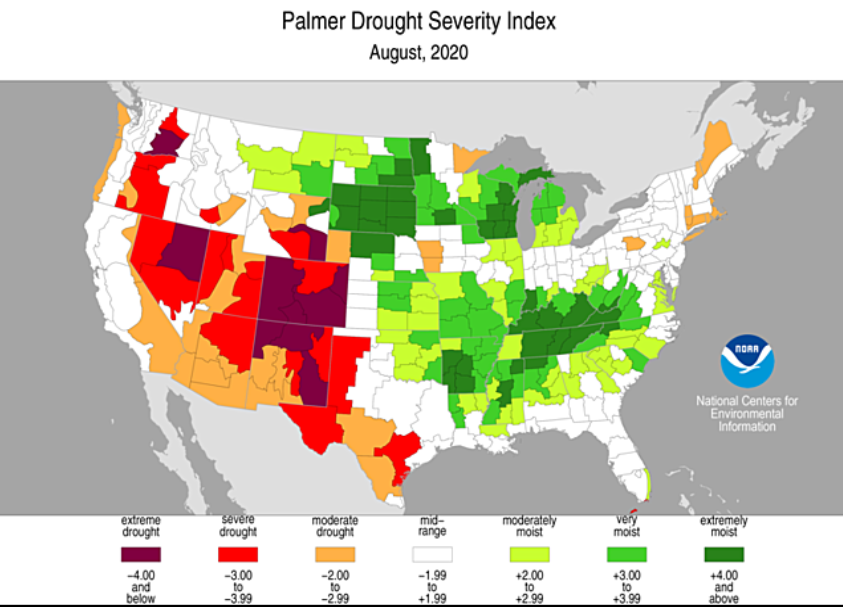

The U.S. Drought Monitor relies on climatological indices (including the

Palmer Drought Severity Index, the

Standardized Precipitation Index, and many others), satellite-based assessments of vegetation health, indicators of soil moisture, and hydrologic data such as streamflow, groundwater, and snowpack.

“There are literally dozens of drought indicators we look at,” Heim says, and sometimes the indicators conflict. “If some of the indices are saying really bad”—i.e., dry—“and a lot of the others are saying really wet, how do you integrate that?”

The answer is known as the “convergence of evidence approach.” The indicators might not all agree precisely, but taken together they point in the same direction.

“You have to mentally assess all of the inputs and make a judgment call,” Heim says. “What are they converging to? That can be hard, and it takes a lot of experience to figure it out.”

Talking to People in the Field

The U.S. Drought Monitor considers information not just from numerical indicators but also from people. Each week, the data are ground-truthed by a network of more than 450 local field experts, many of them meteorologists, climatologists, and hydrologists.

The field experts examine climate data collected at the state level and talk to their own networks of contacts in their local areas, a process that provides crucial linkages between the statistical indicators and the impacts people are experiencing.

“The field experts provide summaries of what’s happening on the ground, and that's very valuable,” Heim says. “Drought isn't just the lack of precipitation, it’s also how drought is impacting people.”

Differentiating Drought

There’s not just one type of drought. The three key types are:

- Meteorological: less precipitation than normal

- Hydrological: how lack of precipitation affects streams, lakes, snowpack, and groundwater

- Agricultural: how lack of precipitation impacts crops and livestock

The three are related but not interchangeable. Meteorological drought can develop quickly, whereas hydrological drought tends to develop more slowly as groundwater depletes and lake levels recede. Agricultural drought, which is closely tied to soil moisture, can develop with great speed when a lack of rain is paired with intense heat (which boosts

evapotranspiration).

“We're trying to reflect all three of these things on one map,” Heim says, and that can be tricky.

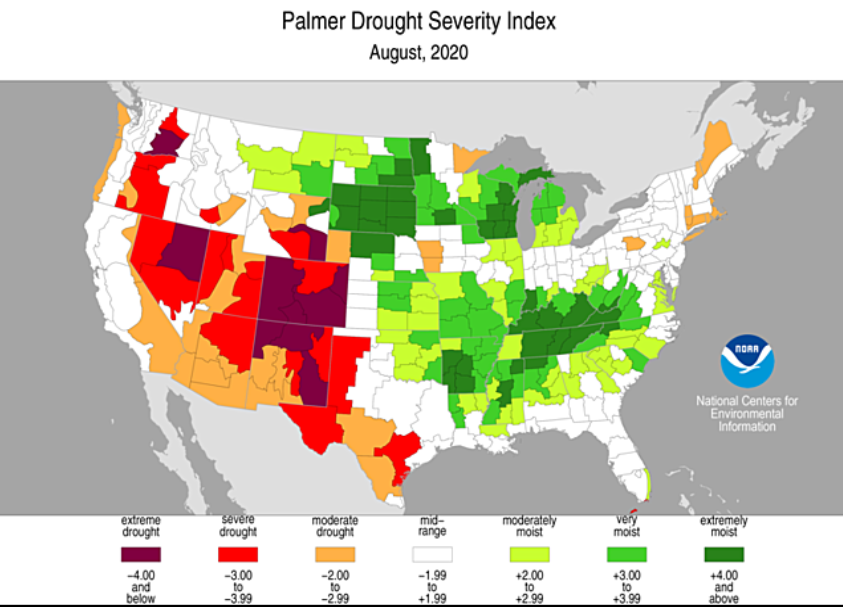

Another complicating factor is time scale. “What happens if you're really dry in the last month or two, but the previous 12 months have been super wet?” Heim asks. That was the situation in the Ohio Valley in the summer of 2020. Meanwhile, New Mexico experienced long-term drought despite on-again, off-again rainy spells.

“What do you put on the map?” Heim asks. “For New Mexico, we're going to show what the long-term conditions are.”

Using the USDM Map

Maps can be downloaded as static images, but the National Drought Mitigation Center, which posts the weekly map, also offers a variety of other tools on its

website. Regional and state maps offer more detailed views than the national map. The

Compare Two Weeks page allows viewing of any two maps side by side. The

Comparison Slider allows users to choose any two dates and then drag a bar across the map to see the change between one date and another. An

Animations page sets a range of maps in motion, showing how drought has expanded and contracted over time. The U.S. Drought Portal at

Drought.gov also shares information from USDM.

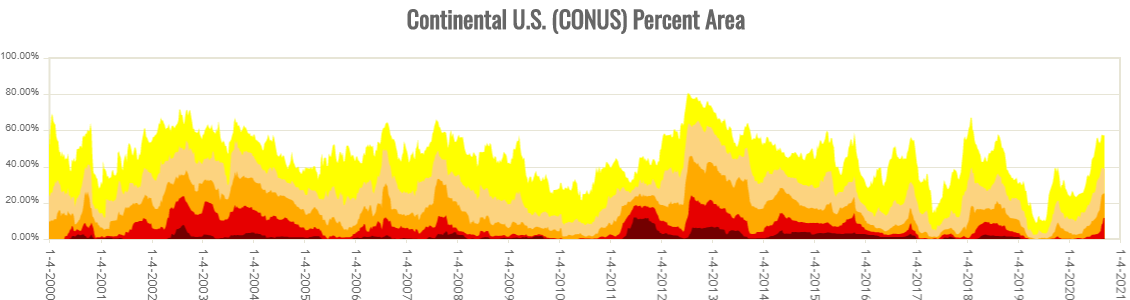

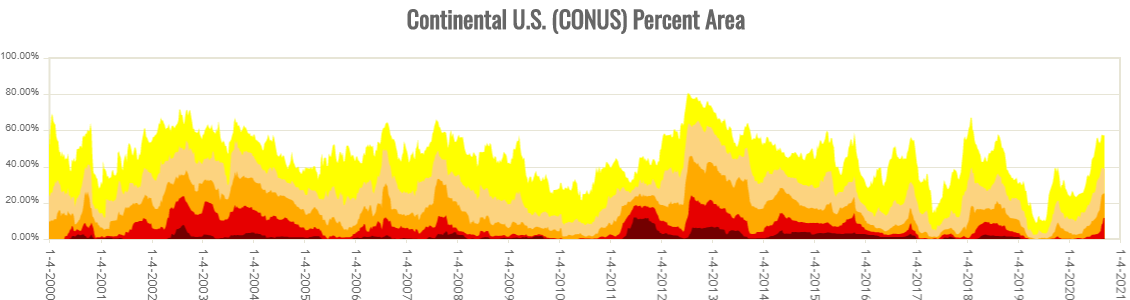

For casual users, Heim recommends using the

USDM Time Series option to see how the percentage area of drought in a state or region changes over time. “It's fascinating to see how the trends of drought have changed over the past 20 years,” he says.

Value of the USDM

The U.S. Drought Monitor matters to a lot of people. Corporations use it to make commercial decisions: a manufacturer of snowblowers might ship fewer units to a northern region in the midst of a snow drought. Operators of a nuclear power plant located along a river keep an eye on hydrological drought, because they need a certain level and temperature of streamflow to cool the reactors. Managers of water supply reservoirs, especially in the West, must monitor drought to ensure water keeps flowing to millions of people.

For farmers, the stakes are particularly high. When the U.S. Drought Monitor level hits D3 (Extreme Drought) in their area, farmers become eligible for certain USDA programs that provide financial relief.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tugBoQf-hfo&feature=youtu.be

“In the past, we have been bombarded with emails and phone calls from farmers and ranchers in areas that are experiencing drought and want us to go D3,” Heim says. Some farmers call their Congressional representatives, who in turn call the scientists at the U.S. Drought Monitor, who must then respectfully explain the USDM’s rigorous scientific methods.

“I grew up in Nebraska. My mother grew up on a farm. I have cousins who are farmers,” Heim says. “When a farmer has their crops destroyed by drought, it's a horrible thing, and it would be great if we could do everything we could to help them recover from that.”

But changes in a region’s drought status are triggered not by sympathy or political pressure but by the data that is painstakingly assembled and analyzed by U.S. Drought Monitor scientists, week after week.

“We follow the methodology,” Heim says. “The U.S. Drought Monitor is a tool that's based upon objective data.”

Edited for WeatherNation by Mace Michaels

“There are literally dozens of drought indicators we look at,” Heim says, and sometimes the indicators conflict. “If some of the indices are saying really bad”—i.e., dry—“and a lot of the others are saying really wet, how do you integrate that?”

The answer is known as the “convergence of evidence approach.” The indicators might not all agree precisely, but taken together they point in the same direction.

“You have to mentally assess all of the inputs and make a judgment call,” Heim says. “What are they converging to? That can be hard, and it takes a lot of experience to figure it out.”

“There are literally dozens of drought indicators we look at,” Heim says, and sometimes the indicators conflict. “If some of the indices are saying really bad”—i.e., dry—“and a lot of the others are saying really wet, how do you integrate that?”

The answer is known as the “convergence of evidence approach.” The indicators might not all agree precisely, but taken together they point in the same direction.

“You have to mentally assess all of the inputs and make a judgment call,” Heim says. “What are they converging to? That can be hard, and it takes a lot of experience to figure it out.”

“We're trying to reflect all three of these things on one map,” Heim says, and that can be tricky.

Another complicating factor is time scale. “What happens if you're really dry in the last month or two, but the previous 12 months have been super wet?” Heim asks. That was the situation in the Ohio Valley in the summer of 2020. Meanwhile, New Mexico experienced long-term drought despite on-again, off-again rainy spells.

“What do you put on the map?” Heim asks. “For New Mexico, we're going to show what the long-term conditions are.”

“We're trying to reflect all three of these things on one map,” Heim says, and that can be tricky.

Another complicating factor is time scale. “What happens if you're really dry in the last month or two, but the previous 12 months have been super wet?” Heim asks. That was the situation in the Ohio Valley in the summer of 2020. Meanwhile, New Mexico experienced long-term drought despite on-again, off-again rainy spells.

“What do you put on the map?” Heim asks. “For New Mexico, we're going to show what the long-term conditions are.”

For casual users, Heim recommends using the

For casual users, Heim recommends using the