Turning Smartphones into a Satellite Imagery Business

Special Stories

24 Apr 2018 9:02 AM

From NASA

Satellites aren’t small or cheap. The Solar Dynamics Observatory launched by NASA in 2010 weighs about 6,800 pounds and cost $850 million to build and put into orbit.

Even the satellites built under NASA’s Discovery Program, aimed at encouraging development of low-cost spacecraft, still have price tags beyond the reach of smaller companies or research organizations: one such satellite, the sun-particle collecting Genesis, ran up $164 million in expenses despite its modest design and mission.

But that’s beginning to change as increasingly powerful technology comes in increasingly smaller packages. For example, in 2010 NASA and the Department of Defense launched the Fast, Affordable, Science and Technology Satellite, aptly called FASTSAT. Weighing in at just 400 pounds, FASTSAT cost significantly less, $10 million, and carried out six experiments in orbit, proving that low-cost, quick-to-assemble spacecraft were possible. You could say that NASA was just getting started.

[In February 2014, Planet Labs Inc. launched its first flock of Dove nanosatellites into space. Shown are two shoebox-sized Doves being ejected into low-Earth orbit from the International Space Station. The company’s goal is for the flock to take a high-resolution snapshot of nearly the entire globe every 24 hours. Credits: NASA]

[In February 2014, Planet Labs Inc. launched its first flock of Dove nanosatellites into space. Shown are two shoebox-sized Doves being ejected into low-Earth orbit from the International Space Station. The company’s goal is for the flock to take a high-resolution snapshot of nearly the entire globe every 24 hours. Credits: NASA]

[Image captured by Planet Labs’ Dove nanosatellites, this one on July 13, 2014, depicts agricultural lands abutting the Yellow River in Pingluo County, northern China. The company notes that a desertification control project is under way to preserve farmland in the area, and that progress can be monitored by examining the landscape as the imagery changes over time.]

By September 2013, a NASA team originally led by Boshuizen and Marshall successfully launched its first PhoneSats into low-Earth orbit at a cost of just $7,000 each. Named Alexander, Graham and Bell, the three mini-orbiters took pictures from space and beamed the data back to Earth, demonstrating for the first time that a consumer-grade smartphone could be used to power a satellite in space. Successive generations of PhoneSats, launched by NASA and housed inside of CubeSats, have since demonstrated increasingly greater capabilities.

Meanwhile, Boshuizen and Marshall — joined by Robbie Schingler, another research scientist at Ames — left NASA to found Planet Labs Inc., a company focused on using cheap, off-the-shelf commercial components to build ever-smaller satellites.

“Instead of doing it the old-school Apollo way, with a lot of system design and analysis and then building the thing at the end, we decided to do it the software way, which is building a minimum-viable prototype first just to show that we have a working model, then going on from there,” Boshuizen says of the process they used to create their satellites, a strategy the company calls “agile aerospace.”

[Image captured by Planet Labs’ Dove nanosatellites, this one on July 13, 2014, depicts agricultural lands abutting the Yellow River in Pingluo County, northern China. The company notes that a desertification control project is under way to preserve farmland in the area, and that progress can be monitored by examining the landscape as the imagery changes over time.]

By September 2013, a NASA team originally led by Boshuizen and Marshall successfully launched its first PhoneSats into low-Earth orbit at a cost of just $7,000 each. Named Alexander, Graham and Bell, the three mini-orbiters took pictures from space and beamed the data back to Earth, demonstrating for the first time that a consumer-grade smartphone could be used to power a satellite in space. Successive generations of PhoneSats, launched by NASA and housed inside of CubeSats, have since demonstrated increasingly greater capabilities.

Meanwhile, Boshuizen and Marshall — joined by Robbie Schingler, another research scientist at Ames — left NASA to found Planet Labs Inc., a company focused on using cheap, off-the-shelf commercial components to build ever-smaller satellites.

“Instead of doing it the old-school Apollo way, with a lot of system design and analysis and then building the thing at the end, we decided to do it the software way, which is building a minimum-viable prototype first just to show that we have a working model, then going on from there,” Boshuizen says of the process they used to create their satellites, a strategy the company calls “agile aerospace.”

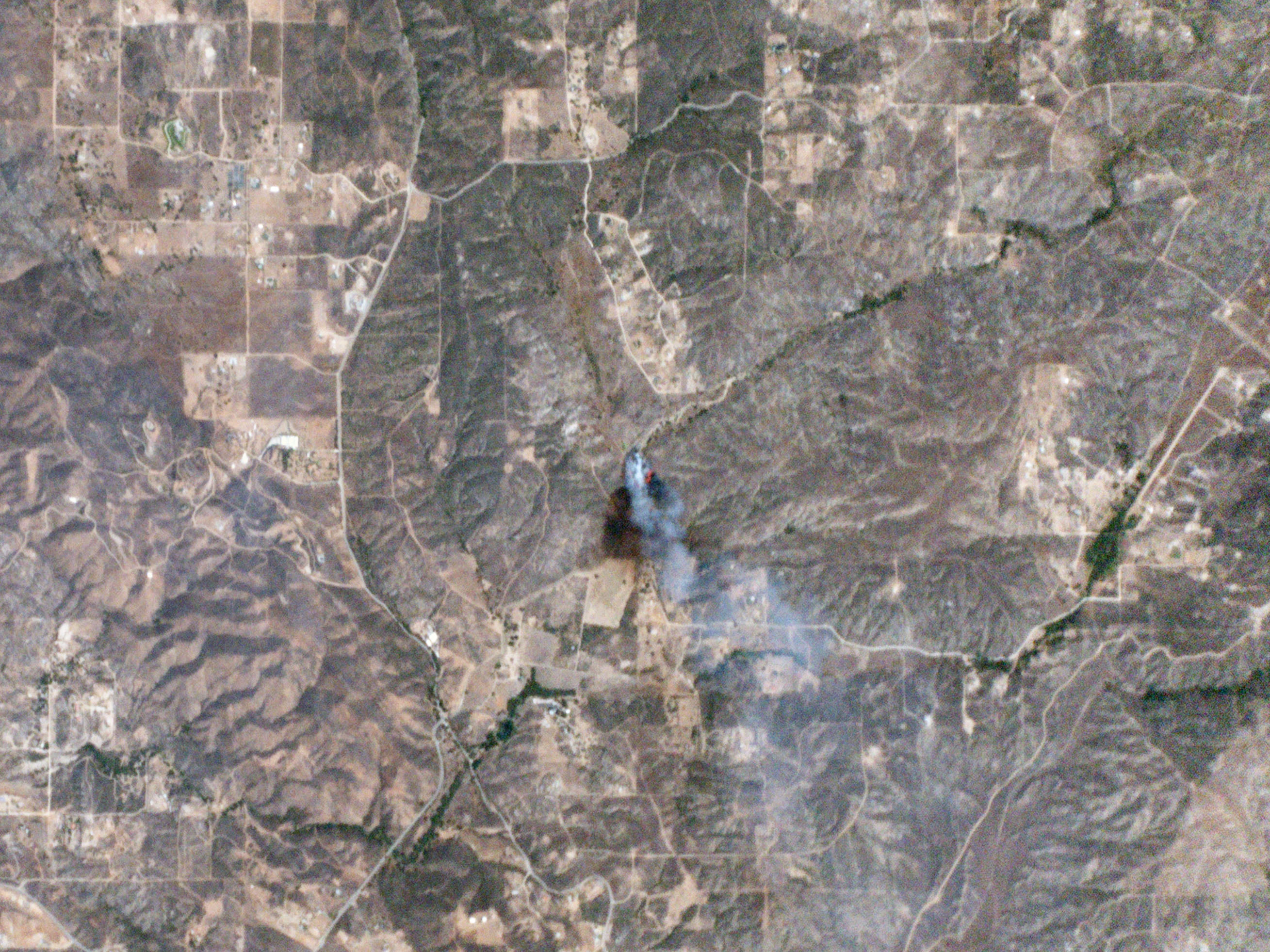

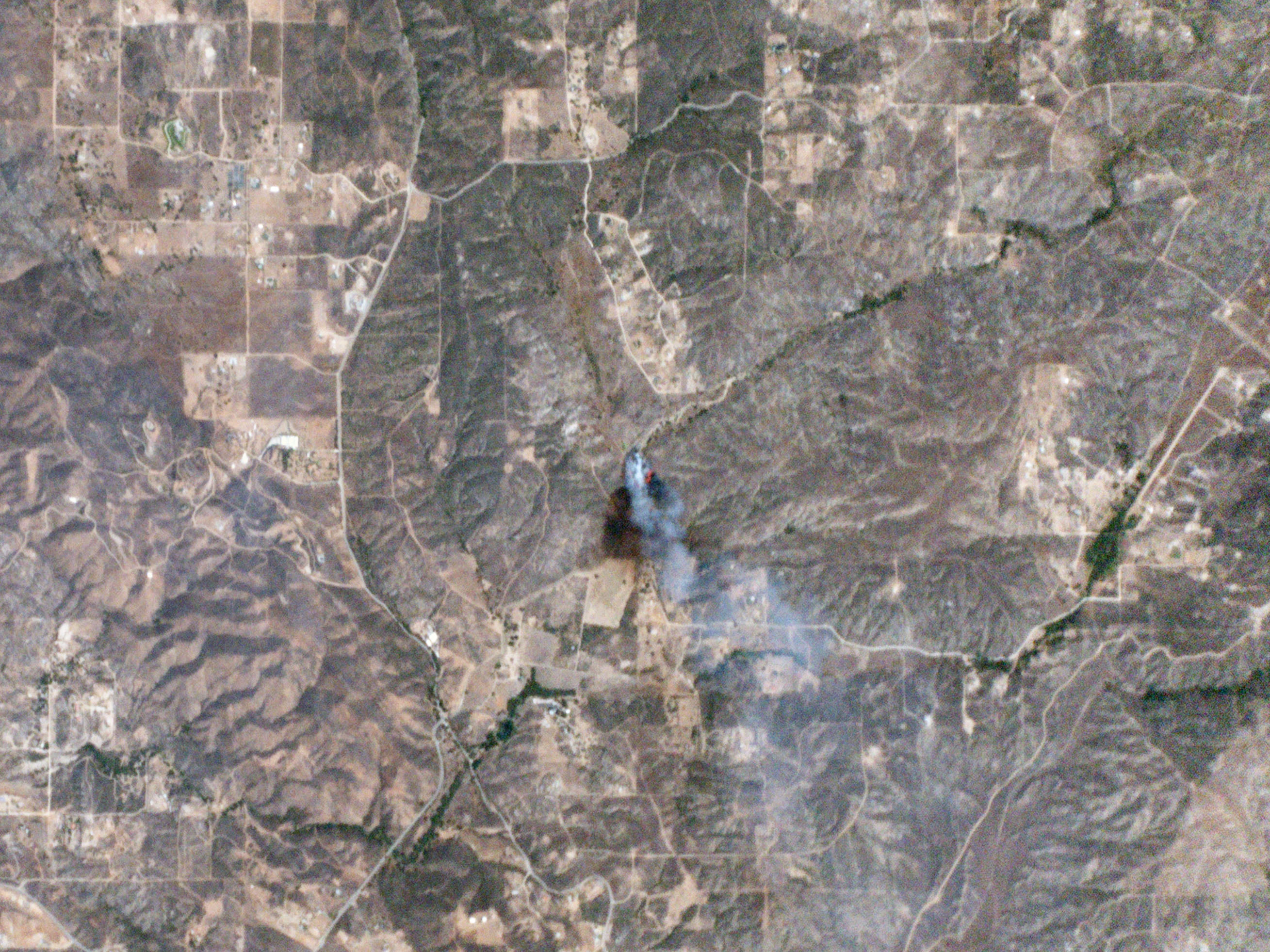

[Planet Labs’ Dove nanosatellites captured this image of the Sabina wildfire in Riverside County, California, on July 23, 2014, just 10 minutes after it was reported. The photo reveals the fire’s size, the path it had burned, the wind direction, and its exact location. Credits: Planet Labs Inc.]

[Planet Labs’ Dove nanosatellites captured this image of the Sabina wildfire in Riverside County, California, on July 23, 2014, just 10 minutes after it was reported. The photo reveals the fire’s size, the path it had burned, the wind direction, and its exact location. Credits: Planet Labs Inc.]

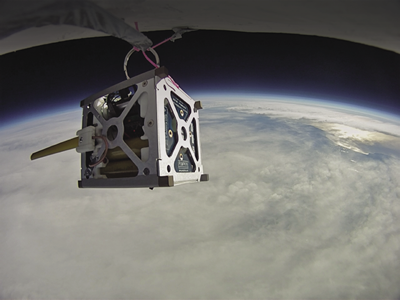

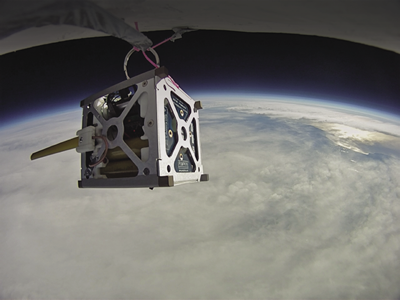

[NASA put its PhoneSat 1.0 nanosatellite through a high-altitude balloon test, replete with a mock mission, to ensure its suitability both for launch and for operating in a space environment. Started in 2009, the PhoneSat project set out to prove that affordable, off-the-shelf commercial parts could be used to build satellites, which have traditionally come with very expensive price tags.]

The private sector is eager for such real-time information. Insurance companies can use the images to verify damages claimed by homeowners and progress on repairs, while commodity trackers can track agricultural crops to forecast yields. The oil and gas industry can monitor pipelines for safety, while mobile-phone companies can use the satellite imagery for improved map applications on smartphones.

The company is dedicated to providing technology that adds environmental and humanitarian value, and Boshuizen says monitoring forests is a top priority.

“If you’re able to plot tree logging in an area where no one is supposed to be logging trees, then you’d be able to do something about it,” he says. “We have the vision of turning insight into action, and what that means is being able to see things and stop them before they become a problem.”

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace Michaels

[NASA put its PhoneSat 1.0 nanosatellite through a high-altitude balloon test, replete with a mock mission, to ensure its suitability both for launch and for operating in a space environment. Started in 2009, the PhoneSat project set out to prove that affordable, off-the-shelf commercial parts could be used to build satellites, which have traditionally come with very expensive price tags.]

The private sector is eager for such real-time information. Insurance companies can use the images to verify damages claimed by homeowners and progress on repairs, while commodity trackers can track agricultural crops to forecast yields. The oil and gas industry can monitor pipelines for safety, while mobile-phone companies can use the satellite imagery for improved map applications on smartphones.

The company is dedicated to providing technology that adds environmental and humanitarian value, and Boshuizen says monitoring forests is a top priority.

“If you’re able to plot tree logging in an area where no one is supposed to be logging trees, then you’d be able to do something about it,” he says. “We have the vision of turning insight into action, and what that means is being able to see things and stop them before they become a problem.”

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace Michaels

[In February 2014, Planet Labs Inc. launched its first flock of Dove nanosatellites into space. Shown are two shoebox-sized Doves being ejected into low-Earth orbit from the International Space Station. The company’s goal is for the flock to take a high-resolution snapshot of nearly the entire globe every 24 hours. Credits: NASA]

[In February 2014, Planet Labs Inc. launched its first flock of Dove nanosatellites into space. Shown are two shoebox-sized Doves being ejected into low-Earth orbit from the International Space Station. The company’s goal is for the flock to take a high-resolution snapshot of nearly the entire globe every 24 hours. Credits: NASA]

Small Wonders

Pete Klupar, director of engineering at Ames Research Center, was fond of pulling a government-issued smartphone out of his pocket during speeches and wondering aloud why the phone, which had a faster processor and better sensors than many satellites, cost so little in comparison — after which he slipped the phone back in his pocket and carried on. An Ames researcher named Chris Boshuizen took Klupar’s musings to heart. Having seen the phone schtick before, Boshuizen and his colleague Will Marshall once interjected during a talk by Klupar when he began to muse aloud about satellite costs. “We said, ‘Pete, don’t put that back in your pocket,’” Boshuizen recalls. “‘We’re going to make that into a satellite.’” [Image captured by Planet Labs’ Dove nanosatellites, this one on July 13, 2014, depicts agricultural lands abutting the Yellow River in Pingluo County, northern China. The company notes that a desertification control project is under way to preserve farmland in the area, and that progress can be monitored by examining the landscape as the imagery changes over time.]

By September 2013, a NASA team originally led by Boshuizen and Marshall successfully launched its first PhoneSats into low-Earth orbit at a cost of just $7,000 each. Named Alexander, Graham and Bell, the three mini-orbiters took pictures from space and beamed the data back to Earth, demonstrating for the first time that a consumer-grade smartphone could be used to power a satellite in space. Successive generations of PhoneSats, launched by NASA and housed inside of CubeSats, have since demonstrated increasingly greater capabilities.

Meanwhile, Boshuizen and Marshall — joined by Robbie Schingler, another research scientist at Ames — left NASA to found Planet Labs Inc., a company focused on using cheap, off-the-shelf commercial components to build ever-smaller satellites.

“Instead of doing it the old-school Apollo way, with a lot of system design and analysis and then building the thing at the end, we decided to do it the software way, which is building a minimum-viable prototype first just to show that we have a working model, then going on from there,” Boshuizen says of the process they used to create their satellites, a strategy the company calls “agile aerospace.”

[Image captured by Planet Labs’ Dove nanosatellites, this one on July 13, 2014, depicts agricultural lands abutting the Yellow River in Pingluo County, northern China. The company notes that a desertification control project is under way to preserve farmland in the area, and that progress can be monitored by examining the landscape as the imagery changes over time.]

By September 2013, a NASA team originally led by Boshuizen and Marshall successfully launched its first PhoneSats into low-Earth orbit at a cost of just $7,000 each. Named Alexander, Graham and Bell, the three mini-orbiters took pictures from space and beamed the data back to Earth, demonstrating for the first time that a consumer-grade smartphone could be used to power a satellite in space. Successive generations of PhoneSats, launched by NASA and housed inside of CubeSats, have since demonstrated increasingly greater capabilities.

Meanwhile, Boshuizen and Marshall — joined by Robbie Schingler, another research scientist at Ames — left NASA to found Planet Labs Inc., a company focused on using cheap, off-the-shelf commercial components to build ever-smaller satellites.

“Instead of doing it the old-school Apollo way, with a lot of system design and analysis and then building the thing at the end, we decided to do it the software way, which is building a minimum-viable prototype first just to show that we have a working model, then going on from there,” Boshuizen says of the process they used to create their satellites, a strategy the company calls “agile aerospace.”

[Planet Labs’ Dove nanosatellites captured this image of the Sabina wildfire in Riverside County, California, on July 23, 2014, just 10 minutes after it was reported. The photo reveals the fire’s size, the path it had burned, the wind direction, and its exact location. Credits: Planet Labs Inc.]

[Planet Labs’ Dove nanosatellites captured this image of the Sabina wildfire in Riverside County, California, on July 23, 2014, just 10 minutes after it was reported. The photo reveals the fire’s size, the path it had burned, the wind direction, and its exact location. Credits: Planet Labs Inc.]

Turning Insight into Action

The first prototypes proved promising enough that the company had no trouble raising funds from venture capitalists. That money, in turn, allowed the company to hire engineers and produce more of the satellites, named Doves, improving them with each iteration until they were ready for full-scale deployment. By February 2014, the company dispatched the first of its commercial “flock,” when 28 Doves were released from the International Space Station. These were followed by further deployments that brought the fleet’s total to more than 130 satellites — enough to produce high-resolution imagery of nearly the entire globe on a daily basis. “We’re going to be gaining insight into the changing planet in a way no one’s ever gotten before,” Boshuizen says of the Doves’ abilities. [NASA put its PhoneSat 1.0 nanosatellite through a high-altitude balloon test, replete with a mock mission, to ensure its suitability both for launch and for operating in a space environment. Started in 2009, the PhoneSat project set out to prove that affordable, off-the-shelf commercial parts could be used to build satellites, which have traditionally come with very expensive price tags.]

The private sector is eager for such real-time information. Insurance companies can use the images to verify damages claimed by homeowners and progress on repairs, while commodity trackers can track agricultural crops to forecast yields. The oil and gas industry can monitor pipelines for safety, while mobile-phone companies can use the satellite imagery for improved map applications on smartphones.

The company is dedicated to providing technology that adds environmental and humanitarian value, and Boshuizen says monitoring forests is a top priority.

“If you’re able to plot tree logging in an area where no one is supposed to be logging trees, then you’d be able to do something about it,” he says. “We have the vision of turning insight into action, and what that means is being able to see things and stop them before they become a problem.”

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace Michaels

[NASA put its PhoneSat 1.0 nanosatellite through a high-altitude balloon test, replete with a mock mission, to ensure its suitability both for launch and for operating in a space environment. Started in 2009, the PhoneSat project set out to prove that affordable, off-the-shelf commercial parts could be used to build satellites, which have traditionally come with very expensive price tags.]

The private sector is eager for such real-time information. Insurance companies can use the images to verify damages claimed by homeowners and progress on repairs, while commodity trackers can track agricultural crops to forecast yields. The oil and gas industry can monitor pipelines for safety, while mobile-phone companies can use the satellite imagery for improved map applications on smartphones.

The company is dedicated to providing technology that adds environmental and humanitarian value, and Boshuizen says monitoring forests is a top priority.

“If you’re able to plot tree logging in an area where no one is supposed to be logging trees, then you’d be able to do something about it,” he says. “We have the vision of turning insight into action, and what that means is being able to see things and stop them before they become a problem.”

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace MichaelsAll Weather News

More