East Troublesome Fire Finally Contained but Exceptional Drought Lingers

Special Stories

2 Dec 2020 10:46 AM

The second largest wildfire in Colorado history has finally been fully contained. As of December 1st, containment of the East Troublesome Fire reached 100% after starting 48 days prior on October 14th.

https://twitter.com/WeatherNation/status/1319232531577884680

You likely remember hearing about this fire after it destroyed homes in the community of Grand Lake, burned into Rocky Mountain National Park, and forced evacuations in the town of Estes Park in the middle of October.

https://twitter.com/WeatherNation/status/1319323128368041985

The fire was also notable for its explosive growth. After four days on October 18th, the fire's size was estimated around 18,000 acres. By the end of the day on the 23rd, the fire had consumed more than 180,000 acres, growing by more than 87,000 acres from October 21st to the 22nd. Luckily, a potent winter storm brought snow to the burn area from the 24th to the 26th, essentially ending any significant growth. Still, hot spots remained and the perimeter of the fire was not contained until more than a month later. Read more about the fire, view maps, and check statistics on the fire's Inciweb page.

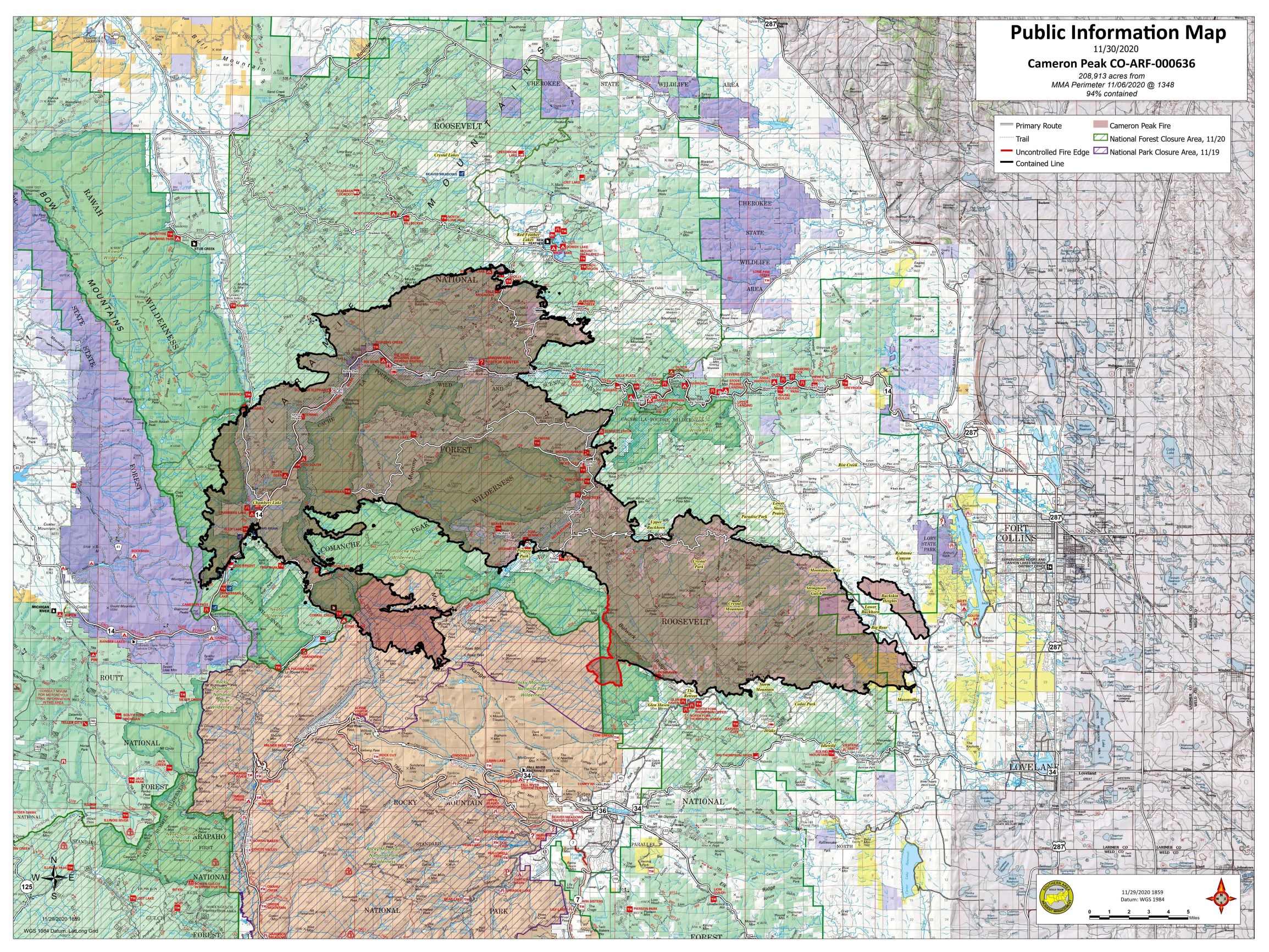

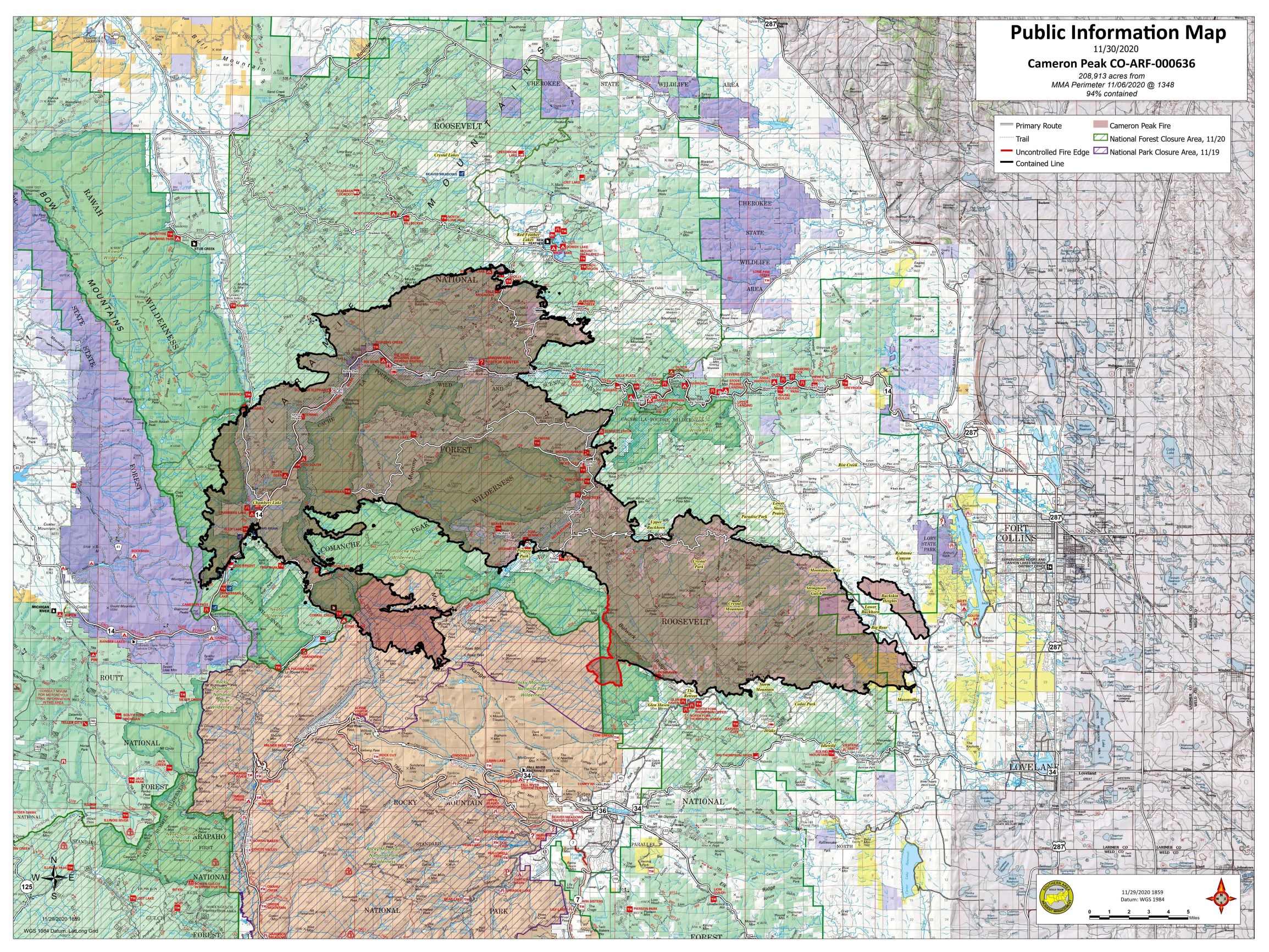

A map showing the area burned by the Cameron Peak Fire through early December. Image courtesy of the National Forest Service.

The largest wildfire in Colorado's history is still not fully contained but progress is being made. As of this article's writing on December 2nd, the Cameron Peak Fire is up to 97% containment, has burned more than 208,000 acres, and destroyed more than 400 structures. It mainly burned to the north of Rocky Mountain National Park, not far from where the East Troublesome Fire grew during that explosive October run.

https://twitter.com/WeatherNation/status/1317541639691194368

Officials were concerned that the Cameron Peak and East Troublesome fires would potentially merge during the period of explosive fire growth in late October, but thankfully the snow fell and the merger never occurred.

A map showing the area burned by the Cameron Peak Fire through early December. Image courtesy of the National Forest Service.

The largest wildfire in Colorado's history is still not fully contained but progress is being made. As of this article's writing on December 2nd, the Cameron Peak Fire is up to 97% containment, has burned more than 208,000 acres, and destroyed more than 400 structures. It mainly burned to the north of Rocky Mountain National Park, not far from where the East Troublesome Fire grew during that explosive October run.

https://twitter.com/WeatherNation/status/1317541639691194368

Officials were concerned that the Cameron Peak and East Troublesome fires would potentially merge during the period of explosive fire growth in late October, but thankfully the snow fell and the merger never occurred.

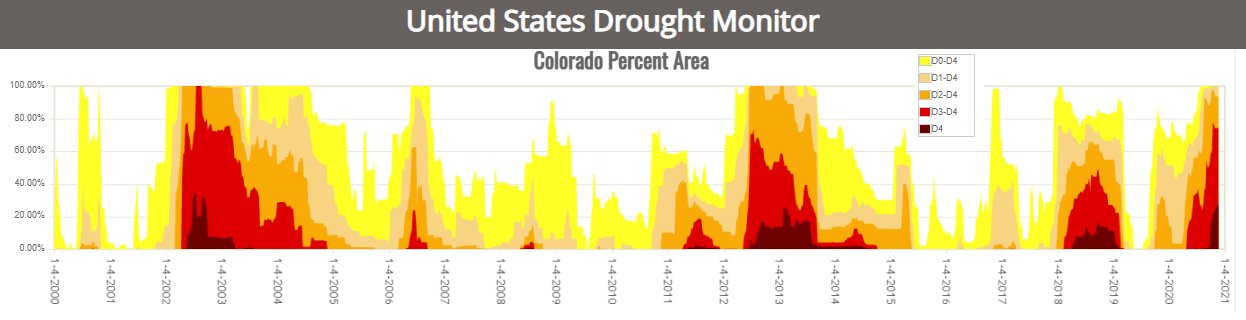

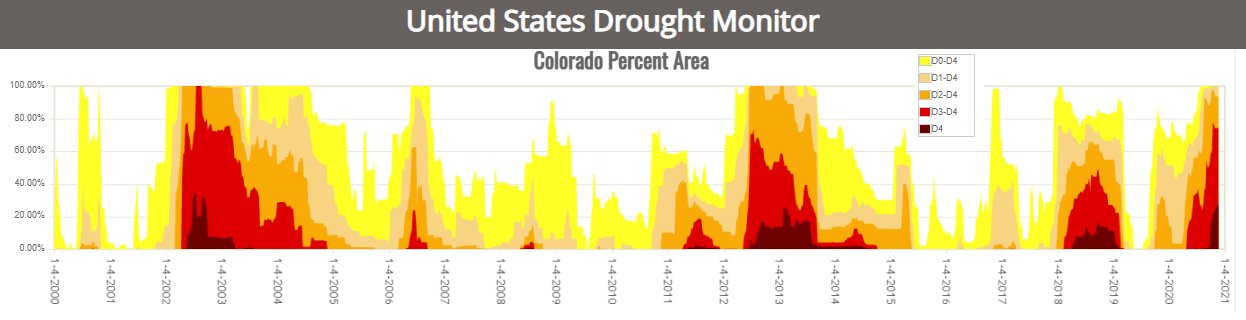

The lack of precipitation has led to widespread drought across Colorado and the Four Corners. The National Weather Service in Boulder recently posted the above time series graphic on their twitter account, stating that the onset of drought in 2020 is comparable to the fall of 2012 in some respects, an historic dry period for portions of the Southwest and California. If wetter conditions do not arrive during the winter and spring seasons, drought conditions could be considerably worse as the fire season ramps up in the summer of 2021.

The lack of precipitation has led to widespread drought across Colorado and the Four Corners. The National Weather Service in Boulder recently posted the above time series graphic on their twitter account, stating that the onset of drought in 2020 is comparable to the fall of 2012 in some respects, an historic dry period for portions of the Southwest and California. If wetter conditions do not arrive during the winter and spring seasons, drought conditions could be considerably worse as the fire season ramps up in the summer of 2021.

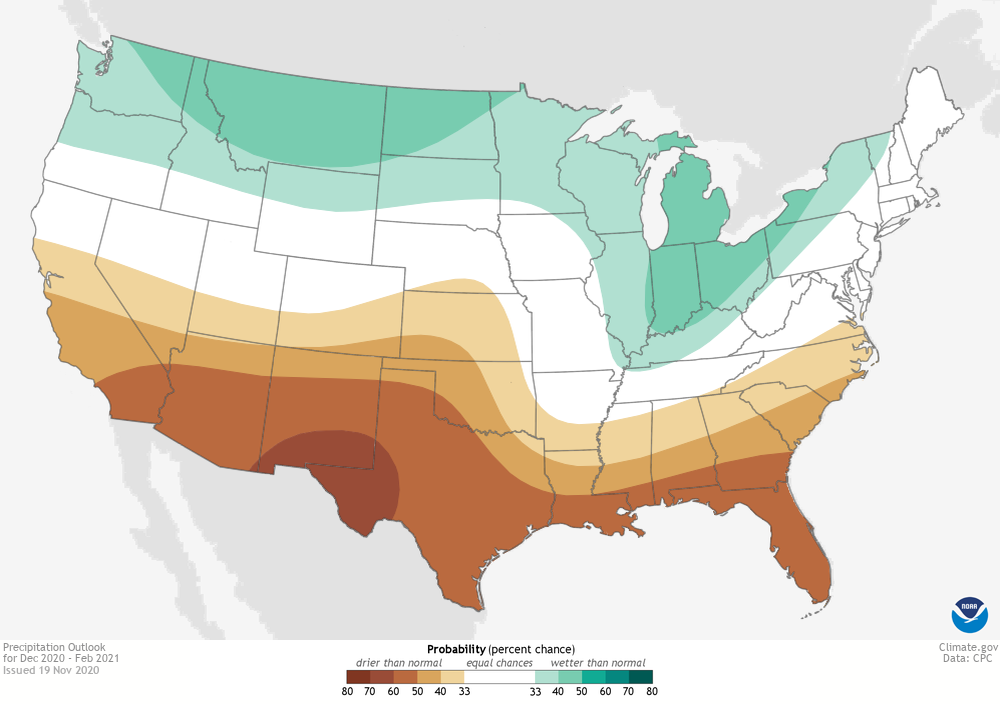

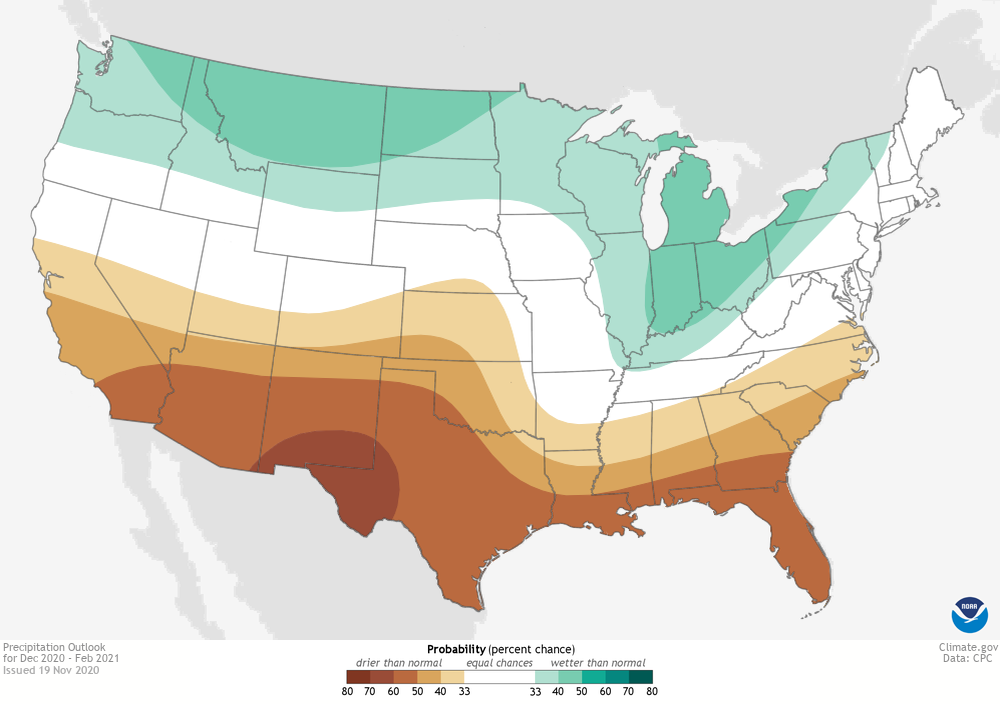

NOAA's updated winter outlook, as shown above, doesn't inspire much confidence that significant ground will be made up in the Southwest through February. The onset of La Niña only adds confidence that most of the four corners will stay drier than average through the winter season. However, seasonal forecasts are notoriously difficult and La Niña produces patterns that vary much more than its warm water counterpart, El Niño.

NOAA's updated winter outlook, as shown above, doesn't inspire much confidence that significant ground will be made up in the Southwest through February. The onset of La Niña only adds confidence that most of the four corners will stay drier than average through the winter season. However, seasonal forecasts are notoriously difficult and La Niña produces patterns that vary much more than its warm water counterpart, El Niño.

A map showing the area burned by the Cameron Peak Fire through early December. Image courtesy of the National Forest Service.

The largest wildfire in Colorado's history is still not fully contained but progress is being made. As of this article's writing on December 2nd, the Cameron Peak Fire is up to 97% containment, has burned more than 208,000 acres, and destroyed more than 400 structures. It mainly burned to the north of Rocky Mountain National Park, not far from where the East Troublesome Fire grew during that explosive October run.

https://twitter.com/WeatherNation/status/1317541639691194368

Officials were concerned that the Cameron Peak and East Troublesome fires would potentially merge during the period of explosive fire growth in late October, but thankfully the snow fell and the merger never occurred.

A map showing the area burned by the Cameron Peak Fire through early December. Image courtesy of the National Forest Service.

The largest wildfire in Colorado's history is still not fully contained but progress is being made. As of this article's writing on December 2nd, the Cameron Peak Fire is up to 97% containment, has burned more than 208,000 acres, and destroyed more than 400 structures. It mainly burned to the north of Rocky Mountain National Park, not far from where the East Troublesome Fire grew during that explosive October run.

https://twitter.com/WeatherNation/status/1317541639691194368

Officials were concerned that the Cameron Peak and East Troublesome fires would potentially merge during the period of explosive fire growth in late October, but thankfully the snow fell and the merger never occurred.

Could the 2021 Fire Season Be Worse?

That's a question that very few want to consider but it's one worth asking. https://twitter.com/NWSBoulder/status/1333288654186360832 An unusually dry summer and fall led to widespread dry fuels for fires to burn through, exacerbating the issue caused by beetle killed trees. The lack of precipitation has led to widespread drought across Colorado and the Four Corners. The National Weather Service in Boulder recently posted the above time series graphic on their twitter account, stating that the onset of drought in 2020 is comparable to the fall of 2012 in some respects, an historic dry period for portions of the Southwest and California. If wetter conditions do not arrive during the winter and spring seasons, drought conditions could be considerably worse as the fire season ramps up in the summer of 2021.

The lack of precipitation has led to widespread drought across Colorado and the Four Corners. The National Weather Service in Boulder recently posted the above time series graphic on their twitter account, stating that the onset of drought in 2020 is comparable to the fall of 2012 in some respects, an historic dry period for portions of the Southwest and California. If wetter conditions do not arrive during the winter and spring seasons, drought conditions could be considerably worse as the fire season ramps up in the summer of 2021.

NOAA's updated winter outlook, as shown above, doesn't inspire much confidence that significant ground will be made up in the Southwest through February. The onset of La Niña only adds confidence that most of the four corners will stay drier than average through the winter season. However, seasonal forecasts are notoriously difficult and La Niña produces patterns that vary much more than its warm water counterpart, El Niño.

NOAA's updated winter outlook, as shown above, doesn't inspire much confidence that significant ground will be made up in the Southwest through February. The onset of La Niña only adds confidence that most of the four corners will stay drier than average through the winter season. However, seasonal forecasts are notoriously difficult and La Niña produces patterns that vary much more than its warm water counterpart, El Niño.All Weather News

More