Mapping May’s Tornado Outbreak: Ingredients for the Perfect Storm

Special Stories

20 Jun 2019 11:06 PM

[Tornado from May 17th Near McCook, NE. Image courtesy @lizszewczykwx on Twitter]

[NOAA] If you thought the two-week tornado outbreak that kicked off on May 17, 2019, seemed out of the ordinary, you certainly weren’t alone. While the weather pattern wasn’t exactly “normal,” Patrick Marsh, a meteorologist with NOAA’s National Weather Service Storm Prediction Center explained that it wasn’t unprecedented or rare either.

“The last few years have been extremely quiet in terms of tornadoes,” Marsh said. “So part of what we’re seeing right now with everybody thinking this is a big, prolonged event is biased by the fact that the last few years have been relatively quiet.”

https://youtu.be/YkgXWnKI6us

While the U.S. has seen fewer tornadoes in recent years, that’s not to say there haven’t been devastating tornadoes. Marsh compared this year’s tornado outbreak to a similar one that occurred during May 2003.

“It started on May 4 (2003) with a high-risk and a tornado that went through Pierce City, Missouri,” Marsh said. “We basically had two weeks of weather where we had quite a bit of the higher-end severe thunderstorms, including several moderate and high-risk events.”

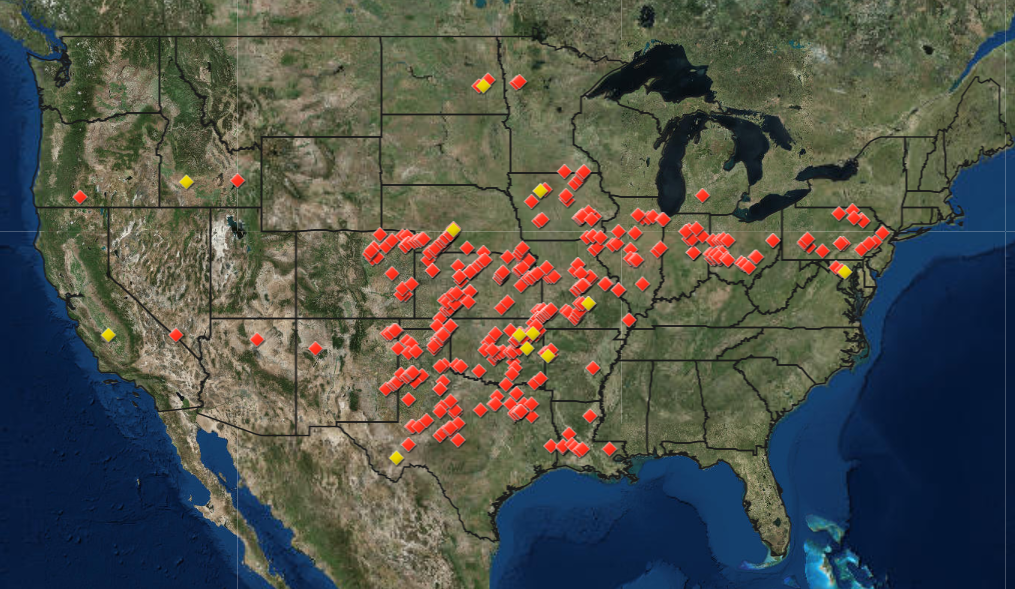

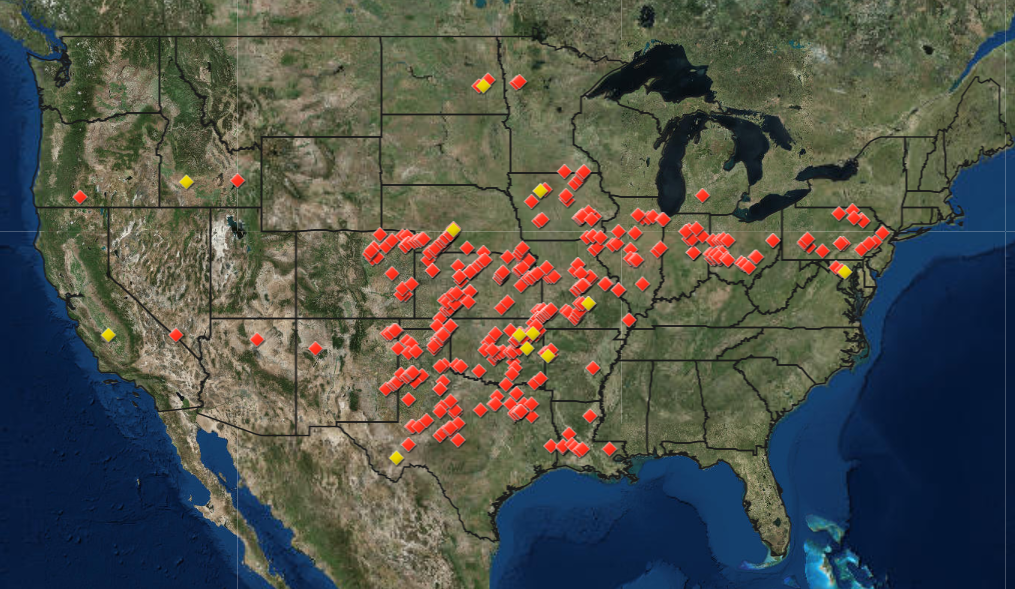

[Each dot represents a preliminary tornado report the National Weather Service received from May 17- 30, 2019. Image from NOAA]

The difference, however, is that in 2003 there were some days between severe weather events. During the latest tornado outbreak, there were 13 straight days with at least eight tornado reports. “That is a new record,” Marsh added.

Until this year, an 11-day stretch from May 28 to June 7, 1980, held the record for the most consecutive days with at least eight confirmed tornadoes. Local National Weather Service offices are still working to conduct damage surveys in areas hit by the recent tornado outbreak, so the total number of confirmed tornadoes may not be available for up to two months.

https://twitter.com/WeatherNation/status/1131477784830681088

[Each dot represents a preliminary tornado report the National Weather Service received from May 17- 30, 2019. Image from NOAA]

The difference, however, is that in 2003 there were some days between severe weather events. During the latest tornado outbreak, there were 13 straight days with at least eight tornado reports. “That is a new record,” Marsh added.

Until this year, an 11-day stretch from May 28 to June 7, 1980, held the record for the most consecutive days with at least eight confirmed tornadoes. Local National Weather Service offices are still working to conduct damage surveys in areas hit by the recent tornado outbreak, so the total number of confirmed tornadoes may not be available for up to two months.

https://twitter.com/WeatherNation/status/1131477784830681088

[Each dot represents a preliminary tornado report the National Weather Service received from May 17- 30, 2019. Image from NOAA]

The difference, however, is that in 2003 there were some days between severe weather events. During the latest tornado outbreak, there were 13 straight days with at least eight tornado reports. “That is a new record,” Marsh added.

Until this year, an 11-day stretch from May 28 to June 7, 1980, held the record for the most consecutive days with at least eight confirmed tornadoes. Local National Weather Service offices are still working to conduct damage surveys in areas hit by the recent tornado outbreak, so the total number of confirmed tornadoes may not be available for up to two months.

https://twitter.com/WeatherNation/status/1131477784830681088

[Each dot represents a preliminary tornado report the National Weather Service received from May 17- 30, 2019. Image from NOAA]

The difference, however, is that in 2003 there were some days between severe weather events. During the latest tornado outbreak, there were 13 straight days with at least eight tornado reports. “That is a new record,” Marsh added.

Until this year, an 11-day stretch from May 28 to June 7, 1980, held the record for the most consecutive days with at least eight confirmed tornadoes. Local National Weather Service offices are still working to conduct damage surveys in areas hit by the recent tornado outbreak, so the total number of confirmed tornadoes may not be available for up to two months.

https://twitter.com/WeatherNation/status/1131477784830681088

What Was Driving These Tornadoes?

First of all, there are three key atmospheric ingredients that have to come together to produce a tornado. First, there has to be moisture in the atmosphere. Instability in the atmosphere — or warm moist air near the ground and cooler dry air aloft — is the second big ingredient, but without wind shear, this doesn’t make it past thunderstorm status. Wind shear — or the change in wind speed and direction with height — is required to get a storm spinning. During the recent tornado outbreak, Marsh explained that a big ridge of high pressure, known as a Bermuda High, got stuck over the Southeastern U.S. The flow around the high was drawing warm, moist air into the central part of the U.S. “Normally, this wouldn’t necessarily be a problem,” Marsh said. “But at the same time, across the Rocky Mountains, a large trough with unseasonably cold air kind of also got stuck.” https://twitter.com/WeatherNation/status/1124119109585686529 The flow around this trough contributed to creating unstable atmospheric conditions across the Central U.S. “In the Central part of the United States, we’ve had moisture, ascent and instability just stuck here because neither one of these two big atmospheric phenomena is moving,” Marsh explained. In addition to seeing these storms in what’s known as “Tornado Alley,” this latest outbreak also produced tornadoes in Pennsylvania and Maryland. Marsh explained this happened because thunderstorms were evolving in the Central U.S. and then lifting north, interacting with a warm front and riding eastward along that front all the way to the Atlantic Ocean. Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace MichaelsAll Weather News

More