We May Be Past The Peak, But Hurricane Season Is Far From Over

Special Stories

5 Oct 2018 9:54 AM

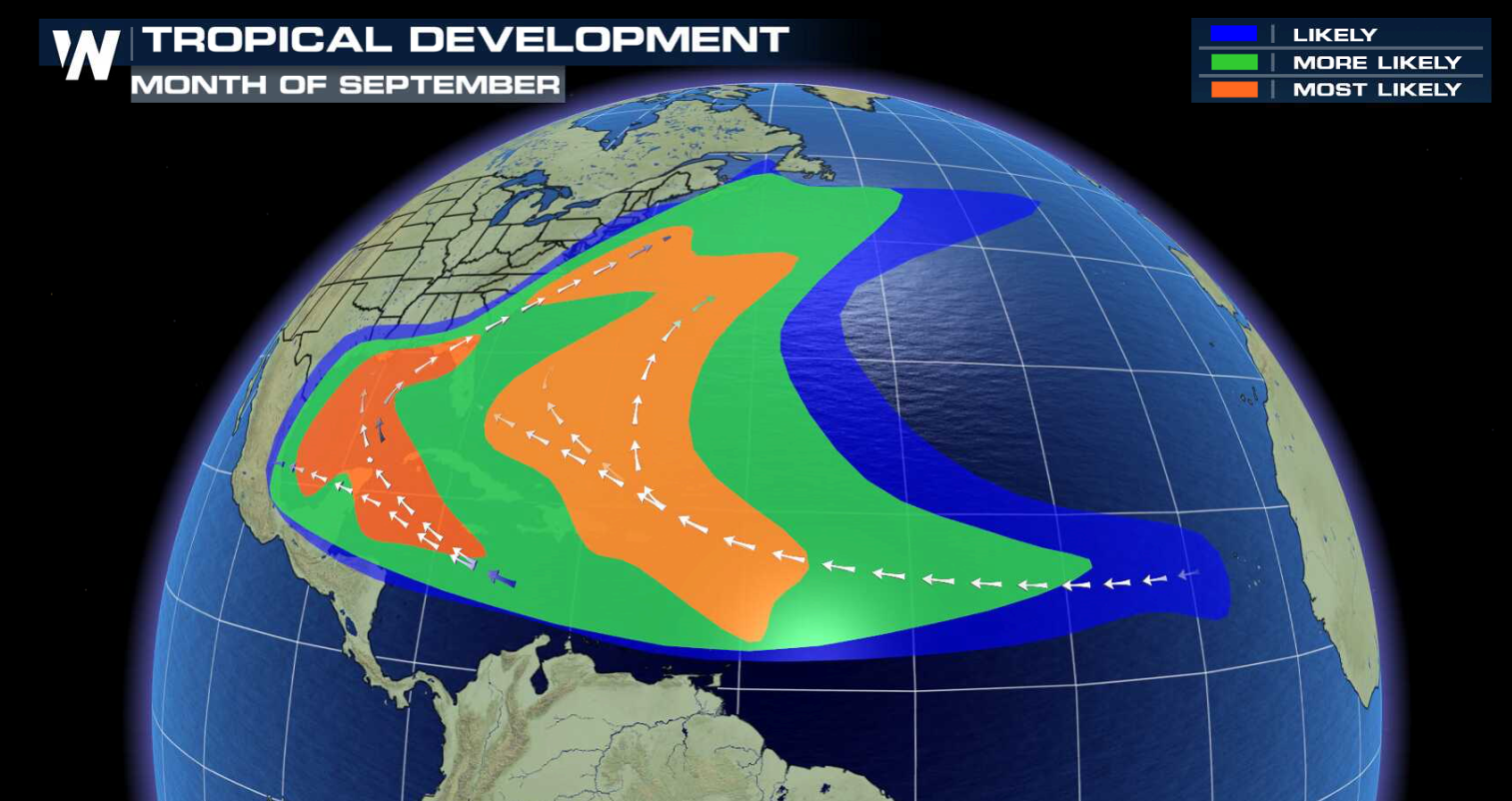

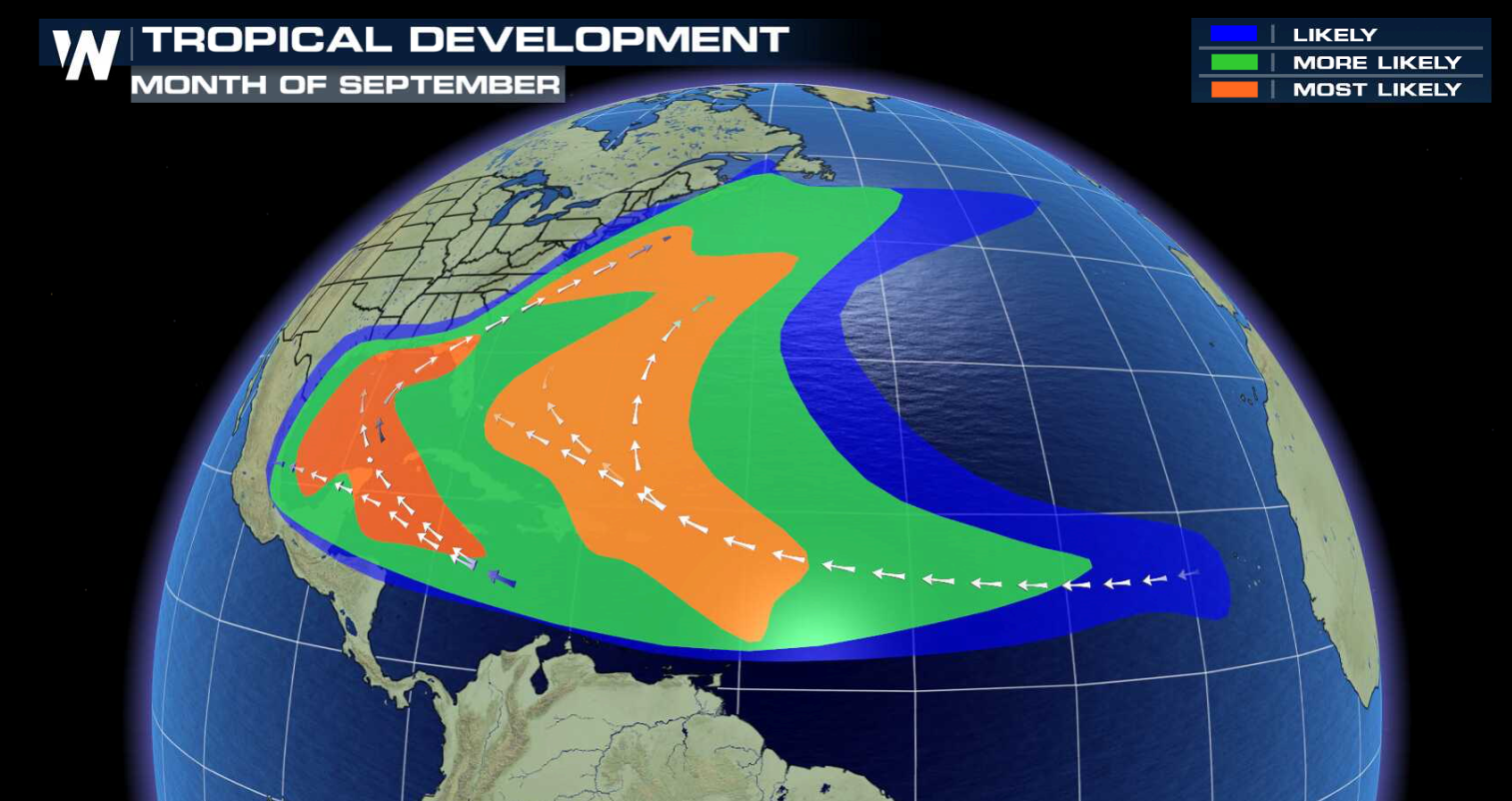

[NOAA] Over the course of a month, we’ve seen tropical cyclone activity in the Atlantic basin heat up quite a bit – most notably with the landfall of Hurricane Florence, which dumped historic amounts of rain on portions of the Carolinas. Although the Atlantic hurricane season runs from June 1 to November 30, on average, early September marks the peak. From 1975 to 2017, there have been an average of 3.1 Atlantic hurricanes per year in September. However, the September of 1998 still holds the record with six hurricanes.

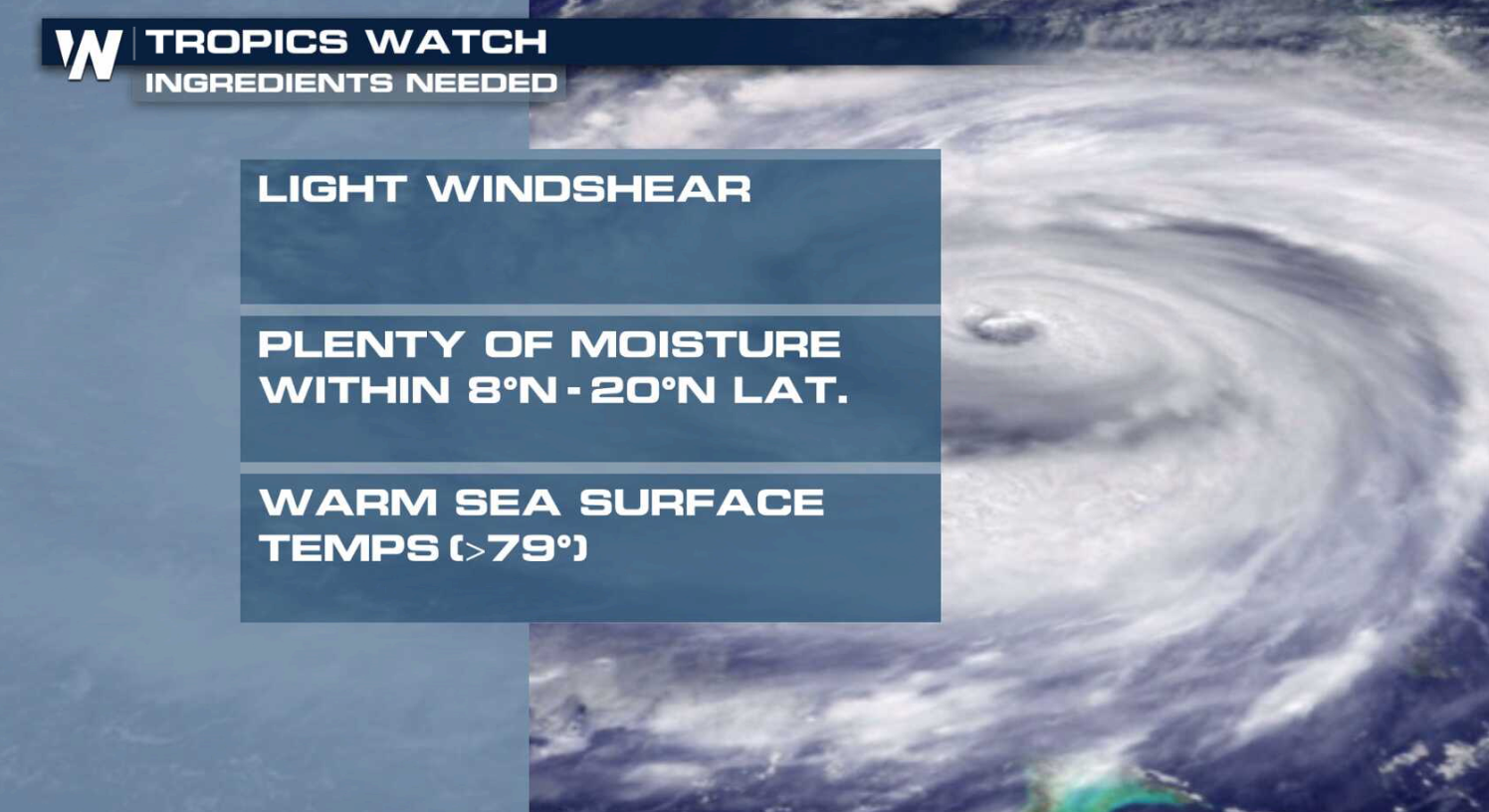

Sea surface temperatures start warming up in late spring and usually must reach a temperature of about 80 degrees Fahrenheit or greater to fuel a hurricane.

“When the tropical Atlantic is warmer than usual, that makes more energy available for the storms so there tends to be greater numbers and more intense hurricanes,” DeMaria said.

Sea surface temperatures start warming up in late spring and usually must reach a temperature of about 80 degrees Fahrenheit or greater to fuel a hurricane.

“When the tropical Atlantic is warmer than usual, that makes more energy available for the storms so there tends to be greater numbers and more intense hurricanes,” DeMaria said.

He added that the distribution of sea surface temperatures around the globe can also indirectly impact the formation of tropical cyclones in the Atlantic basin. During an El Niño period, for instance, when there are warmer than average temperatures in the central and eastern tropical Pacific, vertical wind shear in the Atlantic basin increases, reducing the number of hurricanes in that region.

If this was the only factor for hurricane development, DeMaria said the peak of the season would occur in late September or early October when tropical Atlantic sea surface temperatures are near their annual peak.

He added that the distribution of sea surface temperatures around the globe can also indirectly impact the formation of tropical cyclones in the Atlantic basin. During an El Niño period, for instance, when there are warmer than average temperatures in the central and eastern tropical Pacific, vertical wind shear in the Atlantic basin increases, reducing the number of hurricanes in that region.

If this was the only factor for hurricane development, DeMaria said the peak of the season would occur in late September or early October when tropical Atlantic sea surface temperatures are near their annual peak.

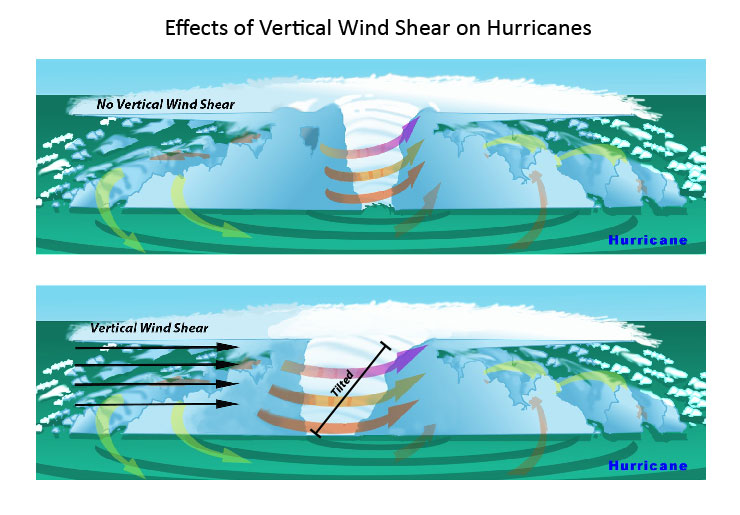

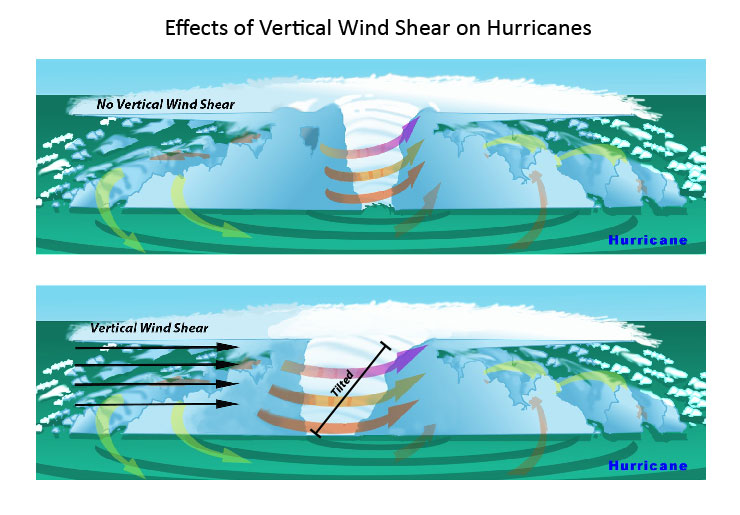

However, warm enough sea surface temperatures aren’t enough to get a tropical cyclone started. Wind shear, which is a change in wind speed or direction over a short distance within the atmosphere, plays a key role. Vertical wind shear can make or break a storm. Too much wind shear can cause a pre-existing disturbance to fall apart.

Low vertical wind shear, which means the upper level winds around the storm aren’t all that different from those in the troposphere (the site where all of Earth’s weather occurs), is key. Little to no vertical wind shear helps keep the storm intact and allows it to gain strength. There tends to be lower vertical wind shear in regions where hurricanes form in the Atlantic basin during late July or early August. It is the combination of the sea surface temperatures and vertical shear effects that results in the early September peak in the Atlantic hurricane season.

However, warm enough sea surface temperatures aren’t enough to get a tropical cyclone started. Wind shear, which is a change in wind speed or direction over a short distance within the atmosphere, plays a key role. Vertical wind shear can make or break a storm. Too much wind shear can cause a pre-existing disturbance to fall apart.

Low vertical wind shear, which means the upper level winds around the storm aren’t all that different from those in the troposphere (the site where all of Earth’s weather occurs), is key. Little to no vertical wind shear helps keep the storm intact and allows it to gain strength. There tends to be lower vertical wind shear in regions where hurricanes form in the Atlantic basin during late July or early August. It is the combination of the sea surface temperatures and vertical shear effects that results in the early September peak in the Atlantic hurricane season.

[In the presence of vertical wind shear, a storm's core structure will be tilted in relationship to the wind shear. This tilting will disrupt the flow of heat and moisture which inhibits the storm from developing and becoming stronger.]

[In the presence of vertical wind shear, a storm's core structure will be tilted in relationship to the wind shear. This tilting will disrupt the flow of heat and moisture which inhibits the storm from developing and becoming stronger.]

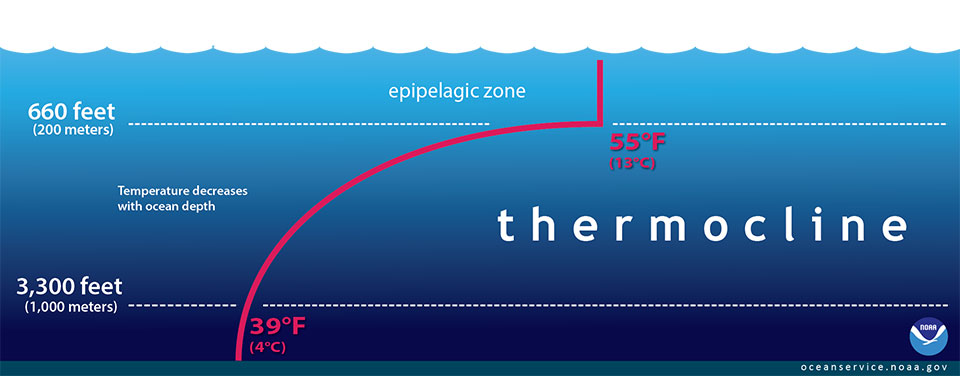

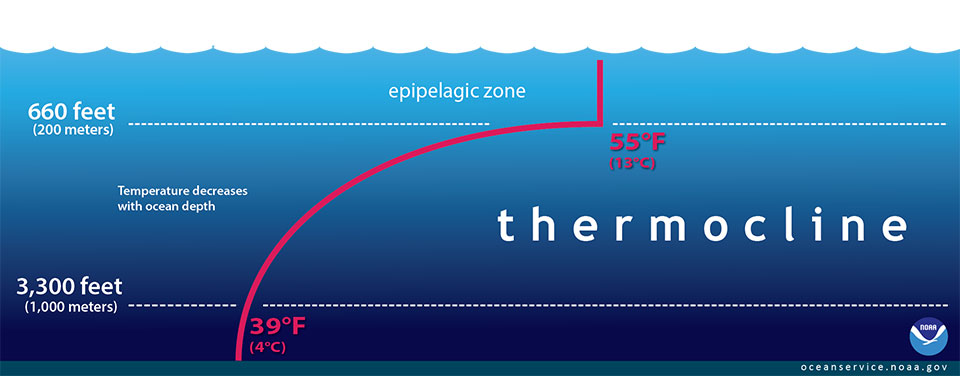

[The red line in this illustration shows a typical seawater temperature profile. In the thermocline, temperature decreases rapidly from the mixed upper layer of the ocean (called the epipelagic zone) to much colder deep water in the thermocline (mesopelagic zone). Below 3,300 feet to a depth of about 13,100 feet, water temperature remains constant. At depths below 13,100 feet, the temperature ranges from near freezing to just above the freezing point of water as depth increases. (NOAA)]

Using instruments known as radar altimeters, Jason-3 provides measurements that help identify areas of warm water, including below the ocean surface, which are needed to fuel tropical cyclones.

Altimeters measure the height of the sea surface, or the sea level. This measurement is important because sea levels can be used to estimate the depth of the thermocline, or the transition layer in a body of water where the mixed warm water from the surface and the cooler water from below meet. By measuring how deep ocean heat extends below the ocean surface, we are better able to estimate tropical cyclone heat potential. Leuliette explained that tropical cyclone heat potential is the estimate of all the heat above the 26 degree Celsius (79 degrees Fahrenheit) isotherm, or the area where the water is 26 degrees Celsius or warmer.

Sea level heights combined with historical hydrographic observations of temperatures in the oceans help estimate the depth of the thermocline. That depth is key to determining a hurricane’s strength because a hurricane doesn’t just rely on warm surface temperatures, it needs a “fuel tank” per se to maintain and gain strength. The deeper the thermocline, the more warm water that is available to fuel the tropical cyclone.

[The red line in this illustration shows a typical seawater temperature profile. In the thermocline, temperature decreases rapidly from the mixed upper layer of the ocean (called the epipelagic zone) to much colder deep water in the thermocline (mesopelagic zone). Below 3,300 feet to a depth of about 13,100 feet, water temperature remains constant. At depths below 13,100 feet, the temperature ranges from near freezing to just above the freezing point of water as depth increases. (NOAA)]

Using instruments known as radar altimeters, Jason-3 provides measurements that help identify areas of warm water, including below the ocean surface, which are needed to fuel tropical cyclones.

Altimeters measure the height of the sea surface, or the sea level. This measurement is important because sea levels can be used to estimate the depth of the thermocline, or the transition layer in a body of water where the mixed warm water from the surface and the cooler water from below meet. By measuring how deep ocean heat extends below the ocean surface, we are better able to estimate tropical cyclone heat potential. Leuliette explained that tropical cyclone heat potential is the estimate of all the heat above the 26 degree Celsius (79 degrees Fahrenheit) isotherm, or the area where the water is 26 degrees Celsius or warmer.

Sea level heights combined with historical hydrographic observations of temperatures in the oceans help estimate the depth of the thermocline. That depth is key to determining a hurricane’s strength because a hurricane doesn’t just rely on warm surface temperatures, it needs a “fuel tank” per se to maintain and gain strength. The deeper the thermocline, the more warm water that is available to fuel the tropical cyclone.

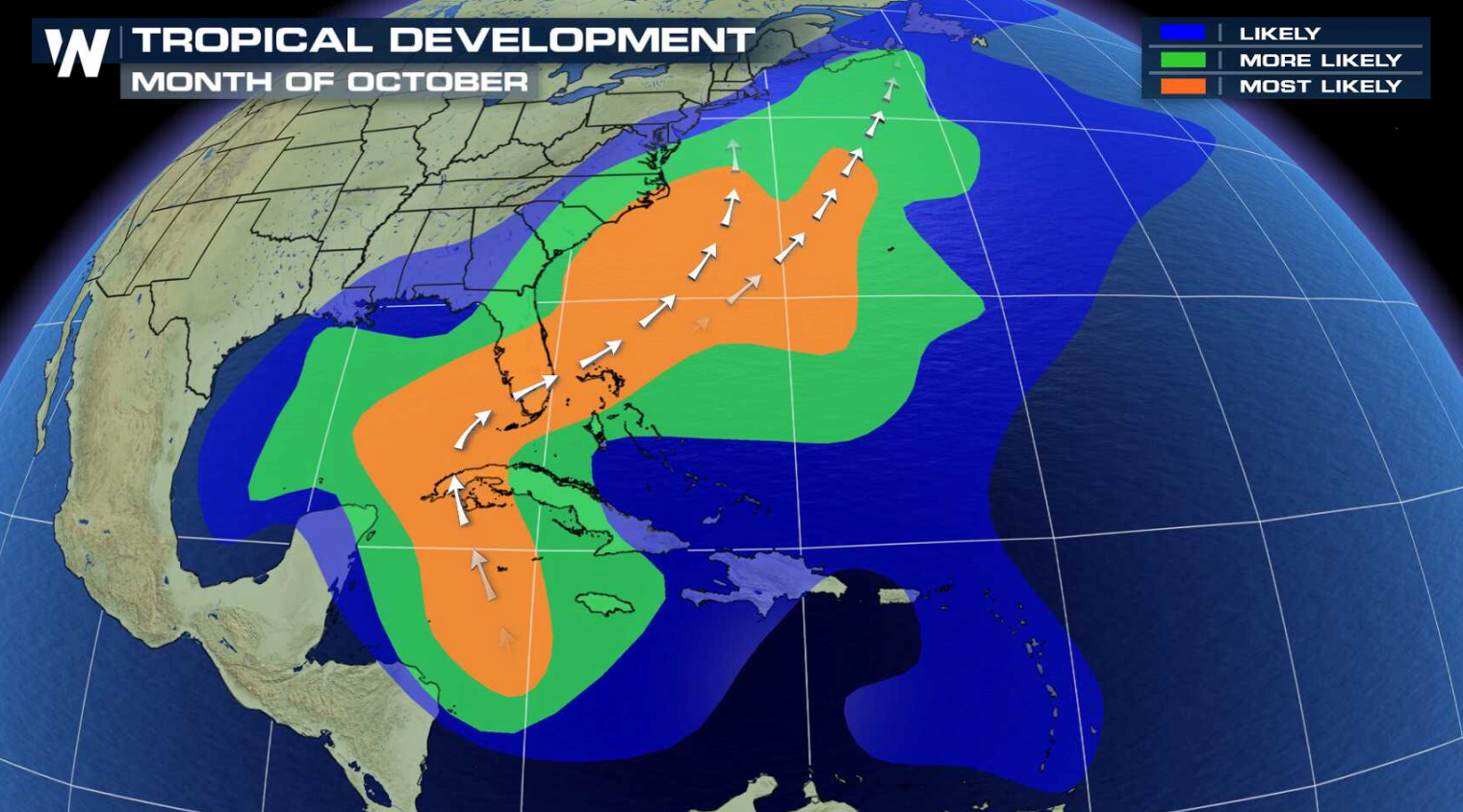

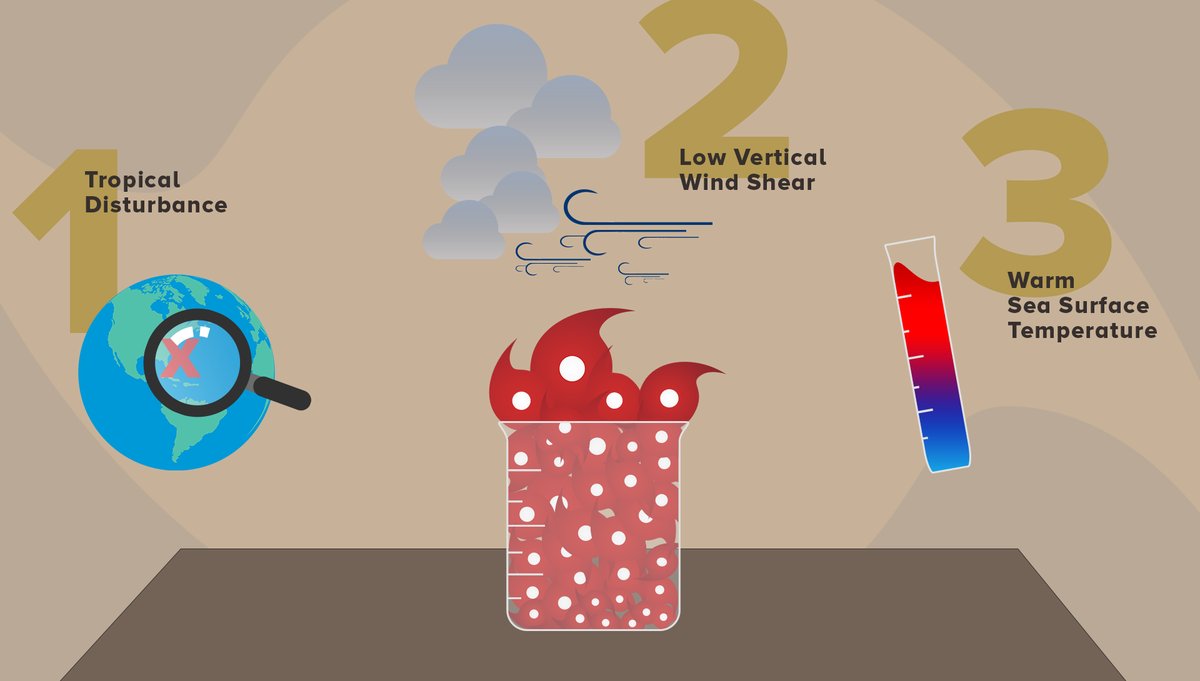

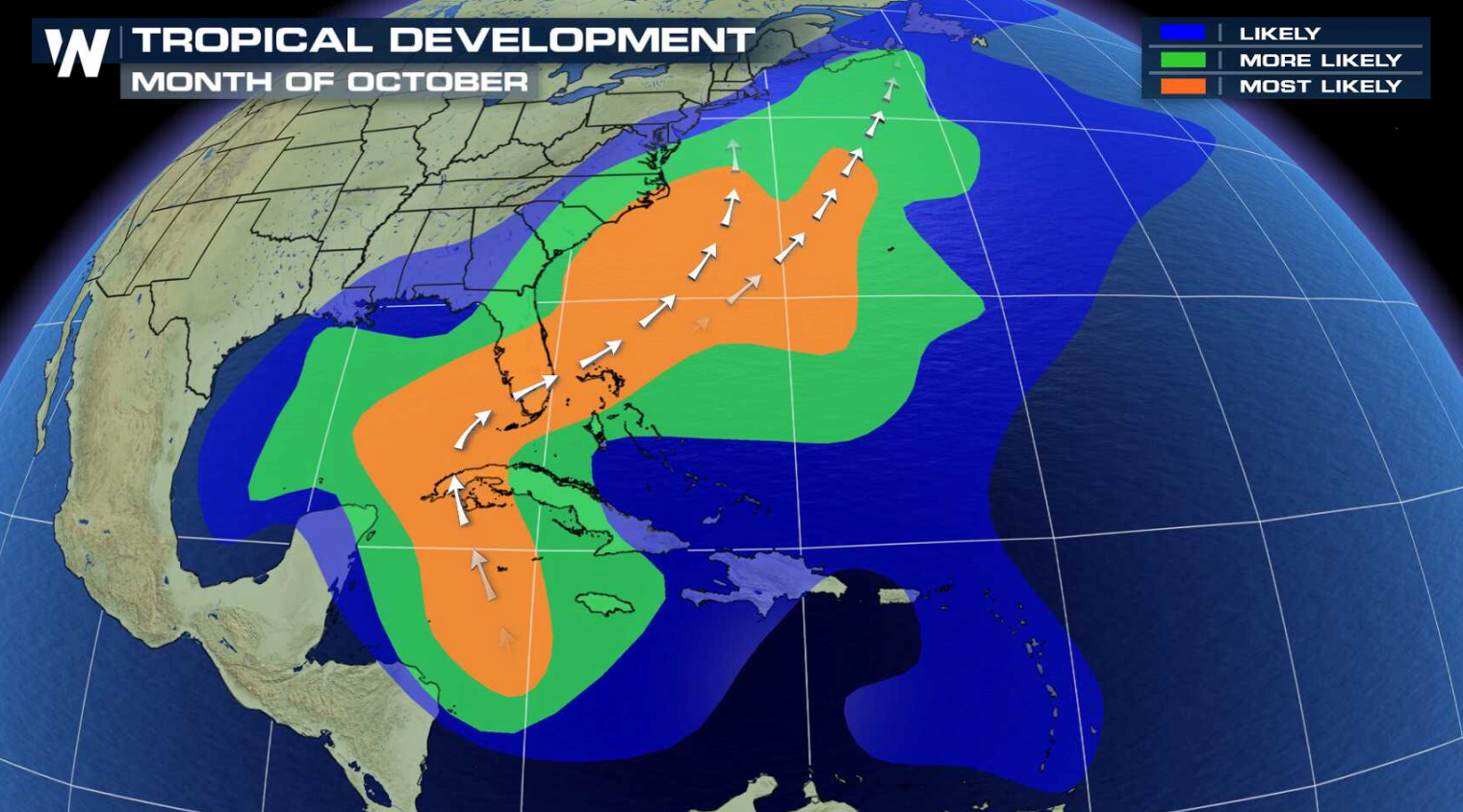

Even though these three “ingredients,” which typically make the Atlantic hurricane season peak in September, become less frequent autumn arrives, it doesn’t mean there’s no chance of seeing a hurricane in October or November.

“In rare circumstances, these conditions can occur outside of the usual hurricane season,” DeMaria added.

In fact, between 1975 and 2017, there have been three Atlantic hurricanes in December, one in May and one January. In other words, the peak may be over, but the season isn’t.

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace Michaels

Even though these three “ingredients,” which typically make the Atlantic hurricane season peak in September, become less frequent autumn arrives, it doesn’t mean there’s no chance of seeing a hurricane in October or November.

“In rare circumstances, these conditions can occur outside of the usual hurricane season,” DeMaria added.

In fact, between 1975 and 2017, there have been three Atlantic hurricanes in December, one in May and one January. In other words, the peak may be over, but the season isn’t.

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace Michaels

So what makes September historically the most active month for the Atlantic basin?

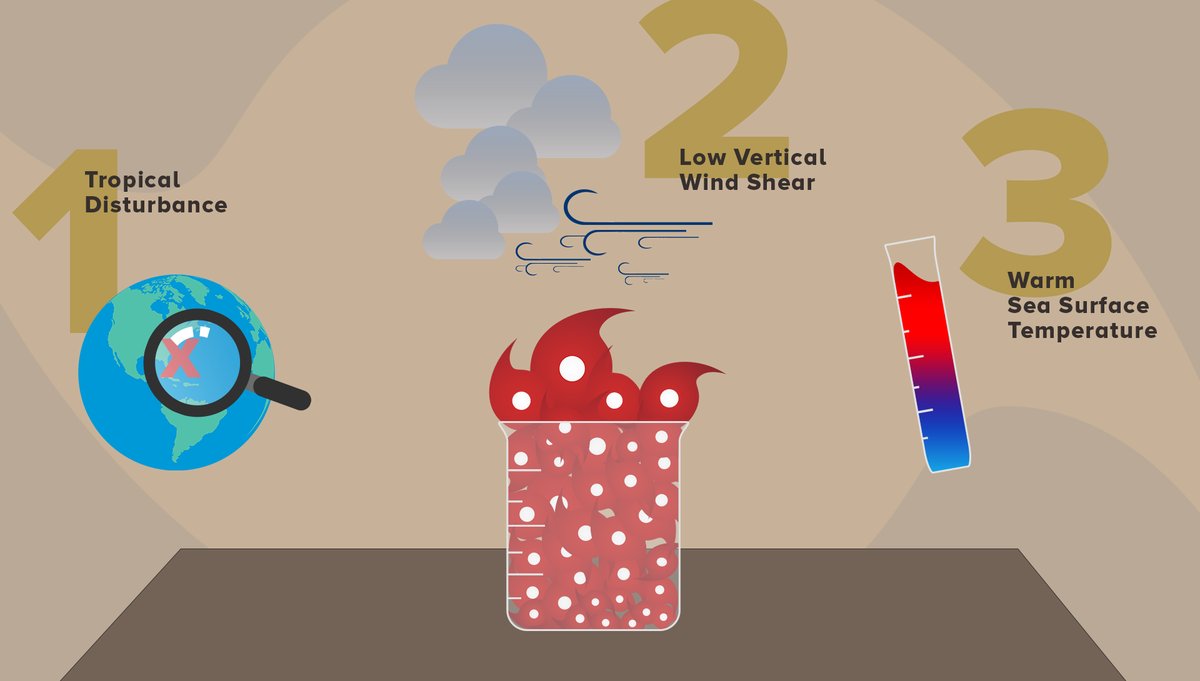

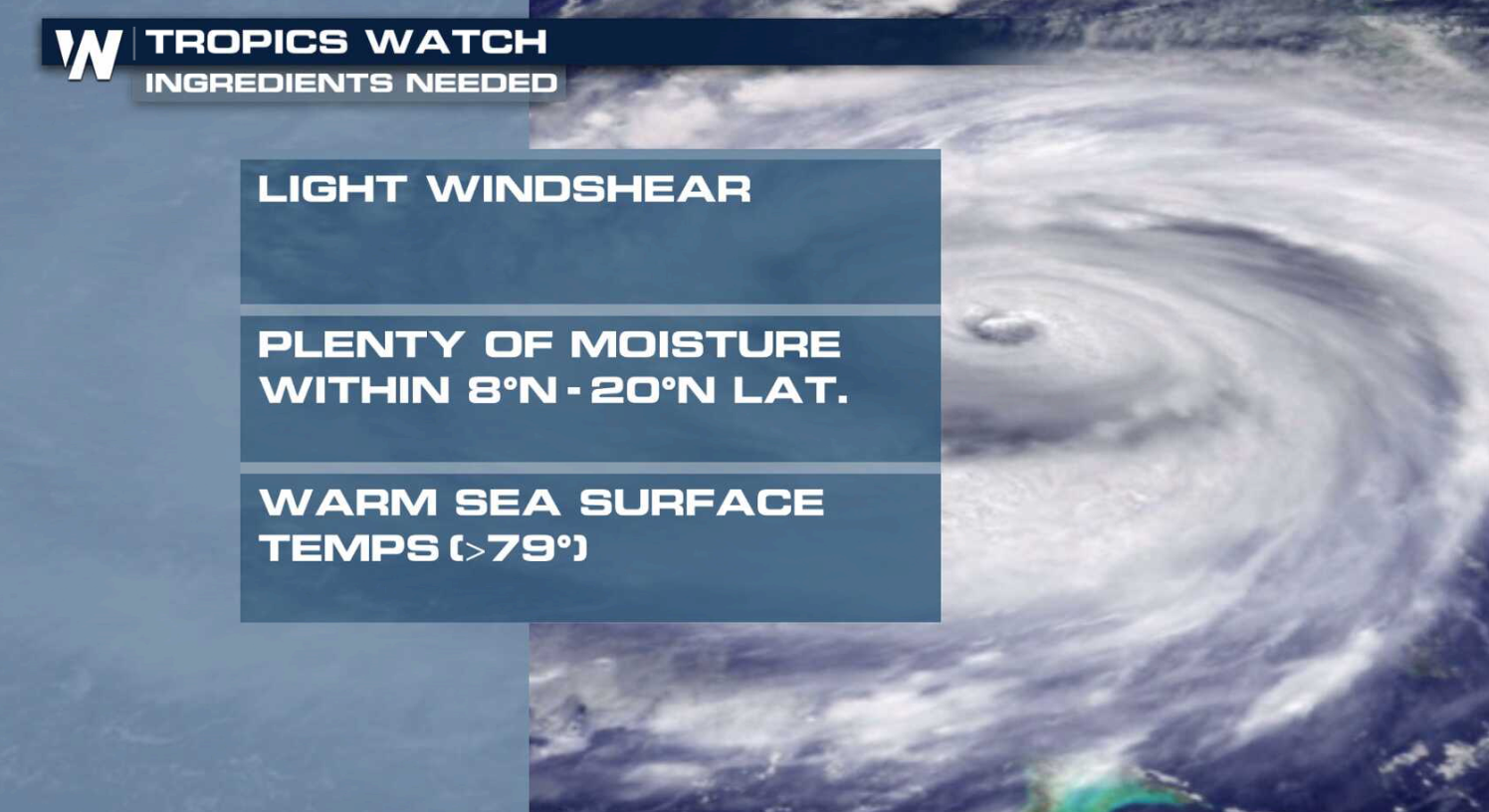

Three basic factors have to come together in September to create the perfect concoction to fuel a hurricane. Hurricane development depends on these three basic factors: sea surface temperature, low vertical wind shear and, of course, a pre-existing disturbance. First, there has to be a pre-existing tropical disturbance, which usually develops in the form of a tropical wave moving off the coast of Africa. Mark DeMaria with NOAA’s National Hurricane Center explained that tropical cyclones can also form at the end of fronts and as a result of rotation “due to low level westerly winds that move into the Caribbean from the east Pacific late in the hurricane season.” Sea surface temperatures start warming up in late spring and usually must reach a temperature of about 80 degrees Fahrenheit or greater to fuel a hurricane.

“When the tropical Atlantic is warmer than usual, that makes more energy available for the storms so there tends to be greater numbers and more intense hurricanes,” DeMaria said.

Sea surface temperatures start warming up in late spring and usually must reach a temperature of about 80 degrees Fahrenheit or greater to fuel a hurricane.

“When the tropical Atlantic is warmer than usual, that makes more energy available for the storms so there tends to be greater numbers and more intense hurricanes,” DeMaria said.

He added that the distribution of sea surface temperatures around the globe can also indirectly impact the formation of tropical cyclones in the Atlantic basin. During an El Niño period, for instance, when there are warmer than average temperatures in the central and eastern tropical Pacific, vertical wind shear in the Atlantic basin increases, reducing the number of hurricanes in that region.

If this was the only factor for hurricane development, DeMaria said the peak of the season would occur in late September or early October when tropical Atlantic sea surface temperatures are near their annual peak.

He added that the distribution of sea surface temperatures around the globe can also indirectly impact the formation of tropical cyclones in the Atlantic basin. During an El Niño period, for instance, when there are warmer than average temperatures in the central and eastern tropical Pacific, vertical wind shear in the Atlantic basin increases, reducing the number of hurricanes in that region.

If this was the only factor for hurricane development, DeMaria said the peak of the season would occur in late September or early October when tropical Atlantic sea surface temperatures are near their annual peak.

However, warm enough sea surface temperatures aren’t enough to get a tropical cyclone started. Wind shear, which is a change in wind speed or direction over a short distance within the atmosphere, plays a key role. Vertical wind shear can make or break a storm. Too much wind shear can cause a pre-existing disturbance to fall apart.

Low vertical wind shear, which means the upper level winds around the storm aren’t all that different from those in the troposphere (the site where all of Earth’s weather occurs), is key. Little to no vertical wind shear helps keep the storm intact and allows it to gain strength. There tends to be lower vertical wind shear in regions where hurricanes form in the Atlantic basin during late July or early August. It is the combination of the sea surface temperatures and vertical shear effects that results in the early September peak in the Atlantic hurricane season.

However, warm enough sea surface temperatures aren’t enough to get a tropical cyclone started. Wind shear, which is a change in wind speed or direction over a short distance within the atmosphere, plays a key role. Vertical wind shear can make or break a storm. Too much wind shear can cause a pre-existing disturbance to fall apart.

Low vertical wind shear, which means the upper level winds around the storm aren’t all that different from those in the troposphere (the site where all of Earth’s weather occurs), is key. Little to no vertical wind shear helps keep the storm intact and allows it to gain strength. There tends to be lower vertical wind shear in regions where hurricanes form in the Atlantic basin during late July or early August. It is the combination of the sea surface temperatures and vertical shear effects that results in the early September peak in the Atlantic hurricane season.

[In the presence of vertical wind shear, a storm's core structure will be tilted in relationship to the wind shear. This tilting will disrupt the flow of heat and moisture which inhibits the storm from developing and becoming stronger.]

[In the presence of vertical wind shear, a storm's core structure will be tilted in relationship to the wind shear. This tilting will disrupt the flow of heat and moisture which inhibits the storm from developing and becoming stronger.]

What role do satellites play in all of this?

Sea surface temperatures are measured using a range of tools including buoys, ocean gliders, geostationary satellites like GOES-16 and low-earth orbiting satellites like Suomi NPP and JPSS-1. However, the ocean temperature below the surface also plays a role in hurricane intensity. Eric Leuliette, who is a research oceanographer at the Laboratory for Satellite Altimetry in College Park, Md., added that the Jason-2 and Jason-3 satellites in particular can help NOAA’s National Weather Service more accurately forecast the strength of tropical cyclones. [The red line in this illustration shows a typical seawater temperature profile. In the thermocline, temperature decreases rapidly from the mixed upper layer of the ocean (called the epipelagic zone) to much colder deep water in the thermocline (mesopelagic zone). Below 3,300 feet to a depth of about 13,100 feet, water temperature remains constant. At depths below 13,100 feet, the temperature ranges from near freezing to just above the freezing point of water as depth increases. (NOAA)]

Using instruments known as radar altimeters, Jason-3 provides measurements that help identify areas of warm water, including below the ocean surface, which are needed to fuel tropical cyclones.

Altimeters measure the height of the sea surface, or the sea level. This measurement is important because sea levels can be used to estimate the depth of the thermocline, or the transition layer in a body of water where the mixed warm water from the surface and the cooler water from below meet. By measuring how deep ocean heat extends below the ocean surface, we are better able to estimate tropical cyclone heat potential. Leuliette explained that tropical cyclone heat potential is the estimate of all the heat above the 26 degree Celsius (79 degrees Fahrenheit) isotherm, or the area where the water is 26 degrees Celsius or warmer.

Sea level heights combined with historical hydrographic observations of temperatures in the oceans help estimate the depth of the thermocline. That depth is key to determining a hurricane’s strength because a hurricane doesn’t just rely on warm surface temperatures, it needs a “fuel tank” per se to maintain and gain strength. The deeper the thermocline, the more warm water that is available to fuel the tropical cyclone.

[The red line in this illustration shows a typical seawater temperature profile. In the thermocline, temperature decreases rapidly from the mixed upper layer of the ocean (called the epipelagic zone) to much colder deep water in the thermocline (mesopelagic zone). Below 3,300 feet to a depth of about 13,100 feet, water temperature remains constant. At depths below 13,100 feet, the temperature ranges from near freezing to just above the freezing point of water as depth increases. (NOAA)]

Using instruments known as radar altimeters, Jason-3 provides measurements that help identify areas of warm water, including below the ocean surface, which are needed to fuel tropical cyclones.

Altimeters measure the height of the sea surface, or the sea level. This measurement is important because sea levels can be used to estimate the depth of the thermocline, or the transition layer in a body of water where the mixed warm water from the surface and the cooler water from below meet. By measuring how deep ocean heat extends below the ocean surface, we are better able to estimate tropical cyclone heat potential. Leuliette explained that tropical cyclone heat potential is the estimate of all the heat above the 26 degree Celsius (79 degrees Fahrenheit) isotherm, or the area where the water is 26 degrees Celsius or warmer.

Sea level heights combined with historical hydrographic observations of temperatures in the oceans help estimate the depth of the thermocline. That depth is key to determining a hurricane’s strength because a hurricane doesn’t just rely on warm surface temperatures, it needs a “fuel tank” per se to maintain and gain strength. The deeper the thermocline, the more warm water that is available to fuel the tropical cyclone.

It ain’t over, till it’s over

Even though these three “ingredients,” which typically make the Atlantic hurricane season peak in September, become less frequent autumn arrives, it doesn’t mean there’s no chance of seeing a hurricane in October or November.

“In rare circumstances, these conditions can occur outside of the usual hurricane season,” DeMaria added.

In fact, between 1975 and 2017, there have been three Atlantic hurricanes in December, one in May and one January. In other words, the peak may be over, but the season isn’t.

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace Michaels

Even though these three “ingredients,” which typically make the Atlantic hurricane season peak in September, become less frequent autumn arrives, it doesn’t mean there’s no chance of seeing a hurricane in October or November.

“In rare circumstances, these conditions can occur outside of the usual hurricane season,” DeMaria added.

In fact, between 1975 and 2017, there have been three Atlantic hurricanes in December, one in May and one January. In other words, the peak may be over, but the season isn’t.

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace MichaelsAll Weather News

More