A Long View of California’s Climate and Wildfires

The new research published by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA examines jet stream and moisture patterns in California over a centuries-long time period—1571 to 2013—which is nearly four times longer than the instrumental period of record that begins in the latter part of the 19th century. The length of the study enhances the understanding of dynamics that may contribute to extreme impacts from wildfires, as well as precipitation extremes. The work provides a stronger foundation and a longer-term perspective for evaluating regional natural hazards within California and the economic risks to one of the world's largest economies.

Between 2012 and 2018, several deadly and costly extreme wildfire events impacted California, including some of the state’s largest and most destructive wildfires on record. In 2018, California experienced several of its costliest, deadliest, and largest wildfires to date, according to records that date back to 1933. Such extreme events, which are tracked by NCEI in its Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters reports, prompt concern for the future. [Photo of scientist examining burned base of tree, courtesy of Carl Skinner, U.S. Forest Service]

Each scientist on the research team brought different perspectives and necessary knowledge to the study. These included expertise in paleoclimatology and paleoecology as well as wildfire research. The international, multi-disciplinary approach needed to execute the research underscored the many factors that can contribute to extreme weather and climate events.

[Photo of scientist examining burned base of tree, courtesy of Carl Skinner, U.S. Forest Service]

Each scientist on the research team brought different perspectives and necessary knowledge to the study. These included expertise in paleoclimatology and paleoecology as well as wildfire research. The international, multi-disciplinary approach needed to execute the research underscored the many factors that can contribute to extreme weather and climate events.

The Jet Stream and Moisture

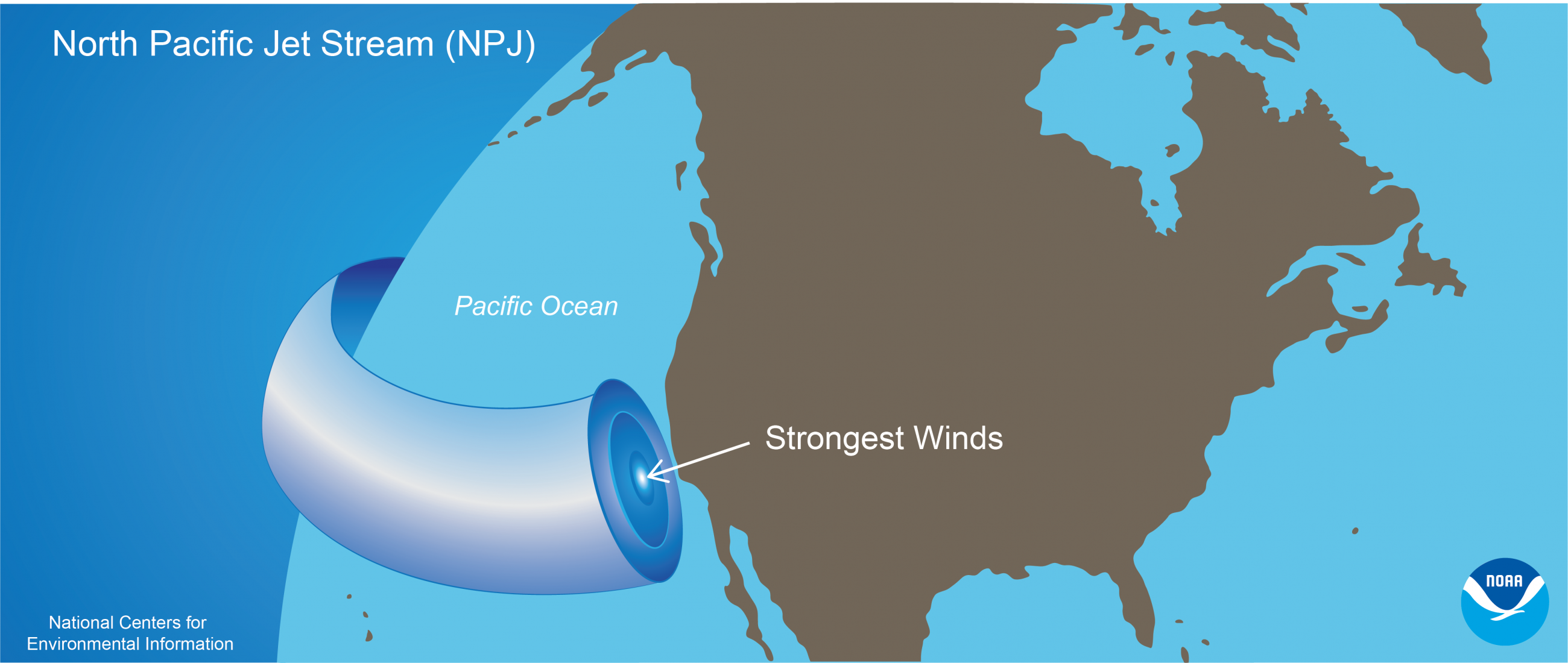

Moisture in California is largely regulated by the strength and position of the North Pacific Jet (NPJ) stream, high-altitude winds that sweep into the state from the west during the cooler wet season. The study evaluated the NPJ between December and February. The strength and position of the winds influence regional conditions that carry over into the warmer dry season, when wildfires are more prone to occur. The wet-season NPJ thus becomes an important precursor of summer fire conditions. To build a better understanding of the influence of the NPJ over time, scientists focused on winter NPJ variability in a period of over 400 years. Using paleoclimatological and historical data, such as tree rings and historical fire records, past conditions were reconstructed to show connections between the NPJ and moisture and forest fire extremes. [The North Pacific Jet (NPJ) travels eastward at variable wind speeds and directions toward California at an altitude of about 11 kilometers above the ocean’s surface. The strength and position of the winds take on importance in relation to the amount and intensity of moisture the jet stream delivers. This graphic represents a winter-average path of entry to California that could produce a very-wet, low-fire season in the state. Courtesy of NOAA NCEI.]

The team wanted to gain a greater sense of conditions before and after fire suppression methods became more standard in 1904. The researchers constructed a list of low- and high-fire years in the Sierra Nevada for 1600–1903 from the paleo records. Extreme instances from both pre- and post-suppression period were then evaluated.

[The North Pacific Jet (NPJ) travels eastward at variable wind speeds and directions toward California at an altitude of about 11 kilometers above the ocean’s surface. The strength and position of the winds take on importance in relation to the amount and intensity of moisture the jet stream delivers. This graphic represents a winter-average path of entry to California that could produce a very-wet, low-fire season in the state. Courtesy of NOAA NCEI.]

The team wanted to gain a greater sense of conditions before and after fire suppression methods became more standard in 1904. The researchers constructed a list of low- and high-fire years in the Sierra Nevada for 1600–1903 from the paleo records. Extreme instances from both pre- and post-suppression period were then evaluated.

Very recently, 2017 bucked a pattern seen in the longer record. The severe Tubbs and Thomas fires of 2017, a high-precipitation year, overrode the NPJ’s historical relationship with low-fire extremes after cool seasons of very high moisture. Extreme precipitation had compromised the Oroville Spillway earlier that year in addition to bringing about dangerous floods and landslides. Prior to modern fire suppression, the paleoclimatic reconstruction showed no cases of a high-precipitation year coupled with a high-fire year. If warming continues, as is the scientific consensus, then significant wet season rain and snow may not ensure a quiet fire season afterward.

“Recent California fires during wet NPJ extremes may be early evidence of this change,” the paper states. Besides fire risk and its associated health and economic impacts, such a change could alter species distribution, forest composition, and ecosystems. Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace Michaels