Kilauea Eruptions: The Way the Wind Blows, so go the Ash and the Gas

NOAA’s HYSPLIT computer model helps forecasters estimate the concentration and movement of SO2 in the air — vital information needed by Hawaii’s emergency responders to make evacuation and other public safety decisions. The model uses wind and other weather data to predict when a plume of toxic gas might drift over population centers.

The first operational HYSPLIT simulation was run by NOAA’s National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office in Honolulu following an eruption on May 3. As events have unfolded, NOAA scientists developed a customized, enhanced version of the operational model used by NOAA forecast offices nationwide. HYSPLIT was developed and is continually refined by scientists at NOAA’s Air Resources Laboratory in College Park, Maryland.

[NWS issues first-ever ashfall advisory for Hawaii after ash plumes rise from the Kilauea volcano. Hawaii, May 15. Credit: U.S. Geological Survey]

A model useful to many

NOAA’s Honolulu forecast office now receives automated forecasts at least four times daily, and can run the model in real time, if needed, to more rapidly predict the movement of gases from cracks in the volcano based on changing wind and weather conditions.

A version of the HYSPLIT model is also being used to warn of hazards to aircraft. When a large eruption on May 17 sent a plume of ash cloud nearly 30,000 feet in the air, NOAA’s Washington Volcanic Ash Advisory Center ran simulations, so NOAA could provide alerts to pilots about potential ash in the atmosphere.

The University of Hawaii at Manoa is also using the model at its Vog Prediction Project to forecast vog, the volcanic equivalent of smog created when sulfur dioxide from the volcano reacts with carbon dioxide, water vapor and sunlight.

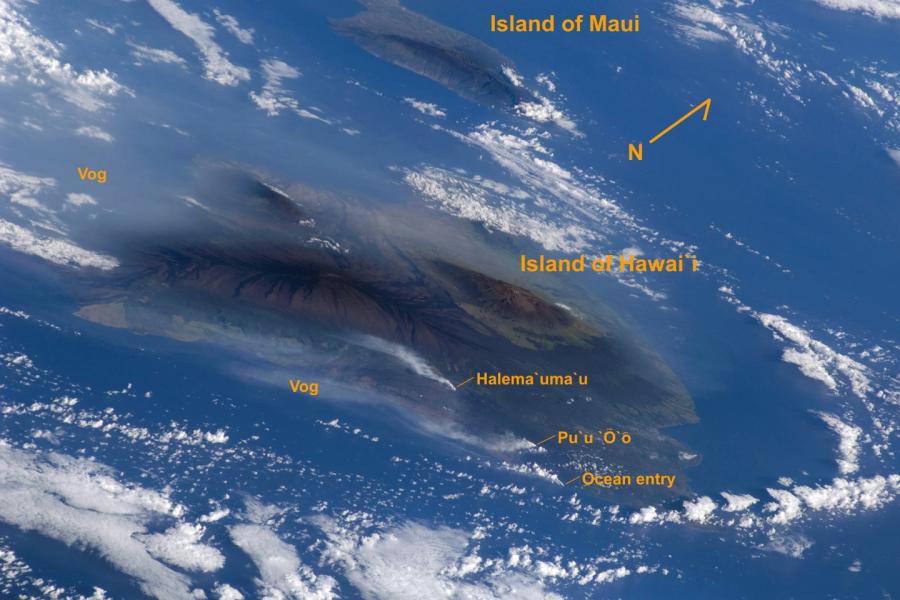

[A view of the Island of Hawai‘i from the Space Shuttle Atlantis in 2009 shows Kīlauea Volcano's gas plumes from its summit, Pu‘u ‘Ō‘ō, and the coastal entry under prevailing northeasterly trade winds.]

Where it goes from here

NOAA’s Honolulu weather forecast office and the U.S. Geological Survey are in close coordination and support local, state and federal emergency managers at multiple locations, including providing critical wind and weather briefings.

Scientists at NOAA’s Air Resources Laboratory will continue to interpret model output as long as it is needed, so that the most accurate information and warnings can be quickly communicated to emergency responders and the people living and traveling in and around Kilauea on Hawaii’s Big Island.

[Lava spattering at Kilauea volcano, Hawaii, May 16. Credit: U.S. Geological Survey]

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace Michaels