New NOAA Hurricane Research Gains Ground

Special Stories

13 Jun 2019 3:59 AM

[Aerial photo of flooding from Hurricane Harvey in west Houston from 2017. Courtesy NOAA Ocean Service]

[NOAA] With significant coastal populations and property at stake, two new studies by NOAA's National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) and its research partners focus on the behavior of tropical cyclones. Because hurricanes can cause fatalities and billions of dollars in damage, the new research could contribute to greater preparedness, improved forecasts, and resiliency efforts.

Tropical cyclones—also referred to as tropical systems, hurricanes, or typhoons—are the most costly U.S. weather and climate disasters. Since 1980, the country has sustained at least 246 weather and climate disasters where overall damages/costs have each reached or exceeded $1 billion (including Consumer Price Index adjustment to 2019). At the end of 2018, the number of billion-dollar tropical cyclones had reached 42 and caused nearly 6,500 deaths in the United States, along with more than $900 billion in damages since 1980.

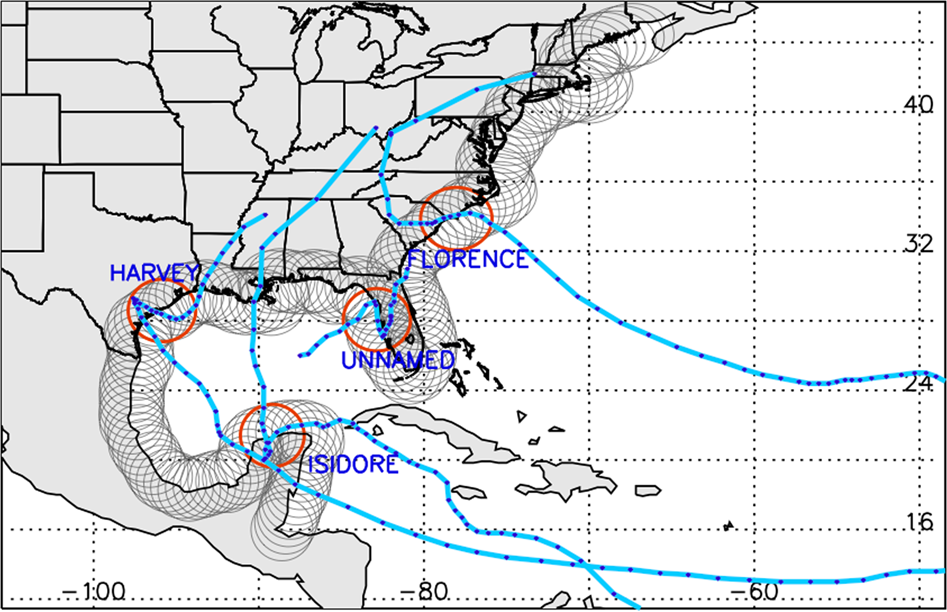

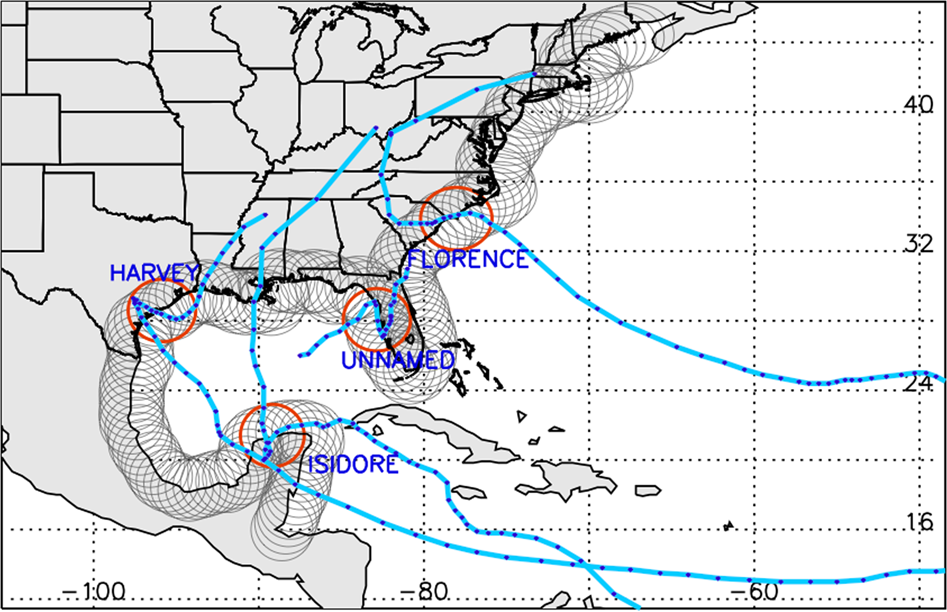

[Examples of four tropical cyclones (blue) that stalled near the coast: Unnamed (1968), Isidore (2002), Harvey (2017), and Florence (2018). Also shown are the 200-km coastal impact regions lining the coast in which residence-time distributions and stalls are computed. In the impact regions shown in red the illustrative storms resided for at least 48 h.]

Followup research further examines the stalling phenomenon by creating a standard of measurement for such events. In “Hurricane stalling along the North American Coast and implications for rainfall,” researchers Tim Hall of NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies and Jim Kossin of NCEI developed a mechanism to explore slowing translation speed.

[Examples of four tropical cyclones (blue) that stalled near the coast: Unnamed (1968), Isidore (2002), Harvey (2017), and Florence (2018). Also shown are the 200-km coastal impact regions lining the coast in which residence-time distributions and stalls are computed. In the impact regions shown in red the illustrative storms resided for at least 48 h.]

Followup research further examines the stalling phenomenon by creating a standard of measurement for such events. In “Hurricane stalling along the North American Coast and implications for rainfall,” researchers Tim Hall of NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies and Jim Kossin of NCEI developed a mechanism to explore slowing translation speed.

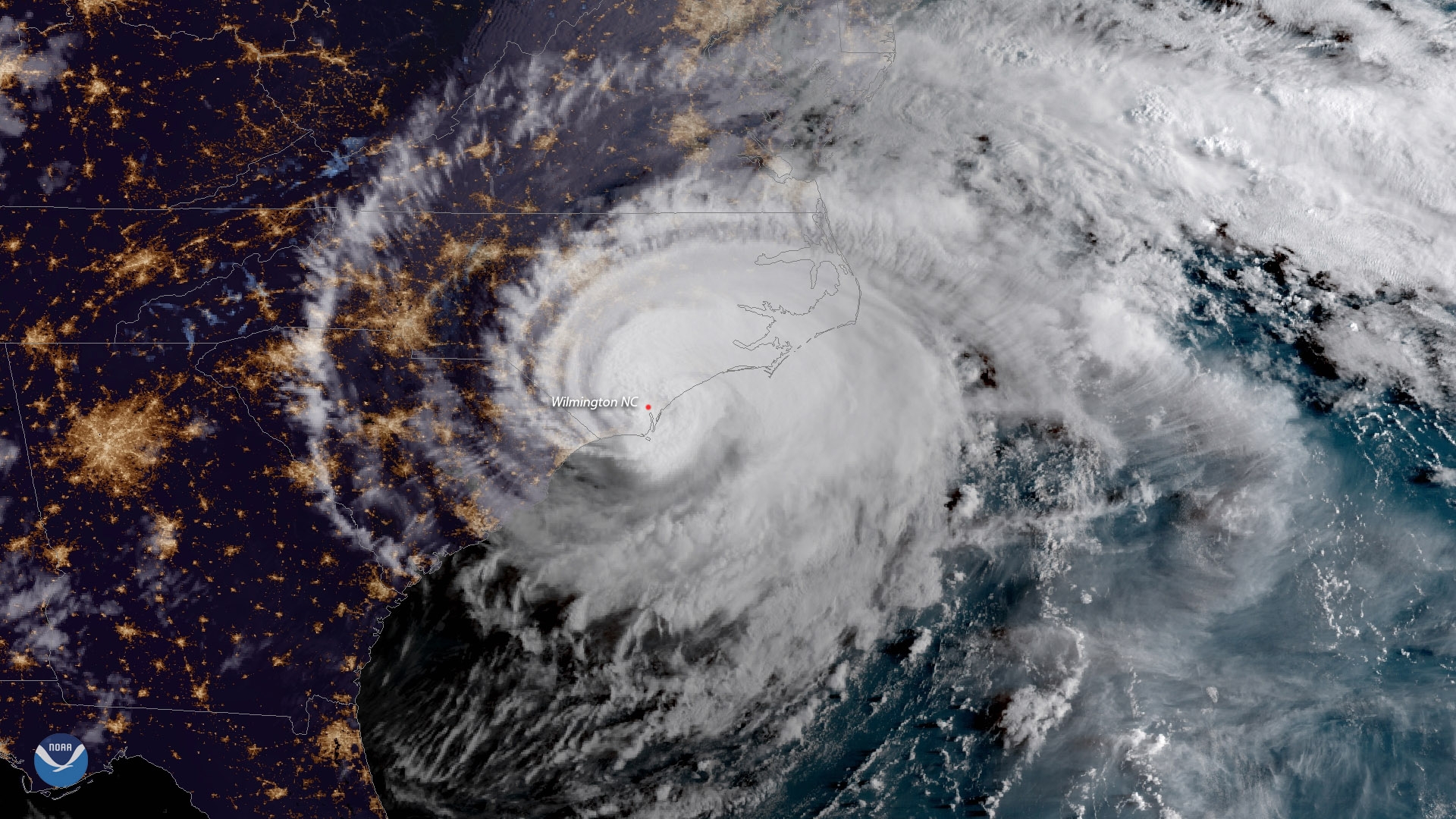

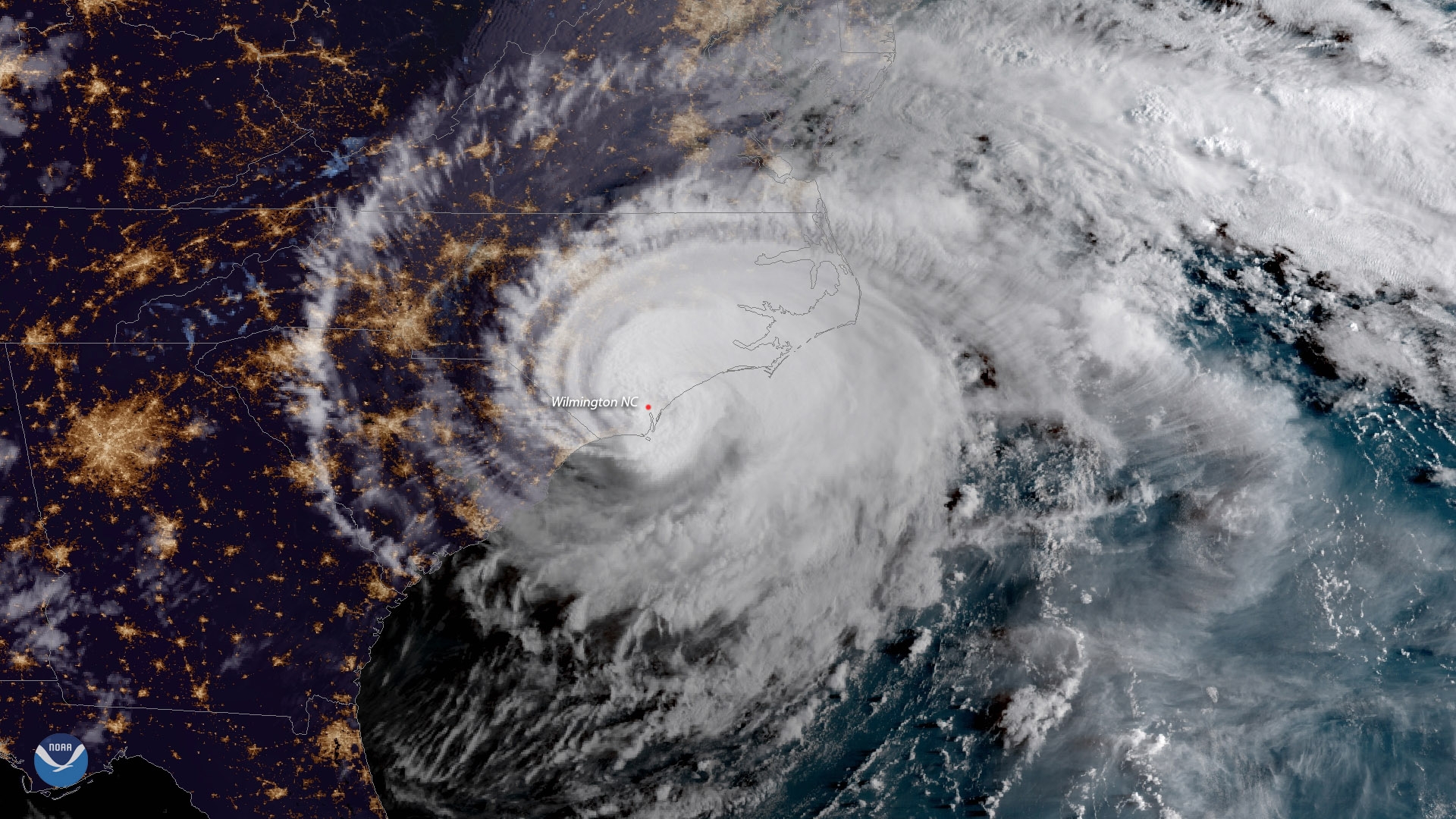

[Hurricane Florence at landfall near Wrightsville Beach, North Carolina on November 9, 2018]

[Hurricane Florence at landfall near Wrightsville Beach, North Carolina on November 9, 2018]

Hurricane Stalling

Research by NCEI published in 2018 found tropical cyclones were taking longer to move along their path, creating a stalling effect, particularly near the coastline. The stalling relates to translation speed, the movement of a storm from place to place rather than the wind speed of the hurricane itself. Stalling increases the likelihood that locations beneath the slower-moving storms are subject to greater rainfall and subsequent flooding. Hurricane Harvey, which struck the Gulf Coast in August 2017, stands as a prime example. As much as 50 inches of rain fell over the course of five days in portions of the Houston metropolitan area, causing catastrophic flooding in the region and contributing to significant fatalities and property loss. [Examples of four tropical cyclones (blue) that stalled near the coast: Unnamed (1968), Isidore (2002), Harvey (2017), and Florence (2018). Also shown are the 200-km coastal impact regions lining the coast in which residence-time distributions and stalls are computed. In the impact regions shown in red the illustrative storms resided for at least 48 h.]

Followup research further examines the stalling phenomenon by creating a standard of measurement for such events. In “Hurricane stalling along the North American Coast and implications for rainfall,” researchers Tim Hall of NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies and Jim Kossin of NCEI developed a mechanism to explore slowing translation speed.

[Examples of four tropical cyclones (blue) that stalled near the coast: Unnamed (1968), Isidore (2002), Harvey (2017), and Florence (2018). Also shown are the 200-km coastal impact regions lining the coast in which residence-time distributions and stalls are computed. In the impact regions shown in red the illustrative storms resided for at least 48 h.]

Followup research further examines the stalling phenomenon by creating a standard of measurement for such events. In “Hurricane stalling along the North American Coast and implications for rainfall,” researchers Tim Hall of NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies and Jim Kossin of NCEI developed a mechanism to explore slowing translation speed.

They found that a greater stalling frequency by tropical cyclones from 1948–2017 drove an increase in annual rainfall in the contiguous United States. Kossin and Hall also found an increasing tendency for abrupt changes in the direction of tropical cyclones, characterizing the shifts as a hurricane’s propensity to meander.

“Reduced speed has the obvious effect of increasing the time over a region, while directional deviations elevate the chance of meandering within the region before exiting,” the authors write in the online open-access scientific journal npj Climate and Atmospheric Science (Nature Partner Journals). [Hurricane Florence at landfall near Wrightsville Beach, North Carolina on November 9, 2018]

[Hurricane Florence at landfall near Wrightsville Beach, North Carolina on November 9, 2018]

Hurricane Intensity

According to another new study, this one from NCEI and the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, greenhouse gases may allow future hurricanes to become stronger on the U.S. East Coast. Researchers posed the question of whether natural variability or human activity were more influential. Of the findings, the team determined that high greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions may contribute to the future rapid intensification of hurricanes along the East Coast. GHG levels, which are increasing in the atmosphere due to daily activities such as energy production and driving, erode a previously defined protective “buffer zone” that had been understood to suppress hurricane intensification. The new research, “Past and Future Hurricane Intensity Change along the U.S. East Coast” published in Scientific Reports, an online academic journal of Nature, examines possible future outcomes based on models of different levels of GHG released into Earth’s atmosphere. In the case of the highest GHG emissions, the erosion of the natural barrier was determined to be especially large. This study suggests a tie to climate change, primarily due to GHG being a major driver of Earth’s warming. Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace MichaelsAll Weather News

More