Research Suggests Outbreaks of Arctic Air Could Be Predicted Weeks or Months in Advance

Special Stories

3 Feb 2021 5:25 AM

You'll likely be hearing a lot about "arctic air" or the "polar vortex" in the days and weeks ahead, as a large portion of the United States is expected to be plunged into a bitter cold airmass escaping from the Great White North.

These arctic air outbreaks can lead to record low temperatures, lake or ocean effect snow, and wind chills cold enough to lead to rapid frostbite or hypothermia. It can also lead to stagnant weather patterns which lead to record rain, snow, or intense winds.

Thankfully, a new paper by NOAA scientist Amy Butler and her colleague, Daniela Domeisen, suggests these events could be predicted weeks or even months in advance with further study and improved numerical weather models. You can read a short summary of the paper on NOAA's website.

Greater lead time ahead of these cold blasts could mean cities are better prepared to care for homeless populations or cancel school when travel is too dangerous, and those working in agriculture would know far in advance when livestock needs to be brought in to shelter.

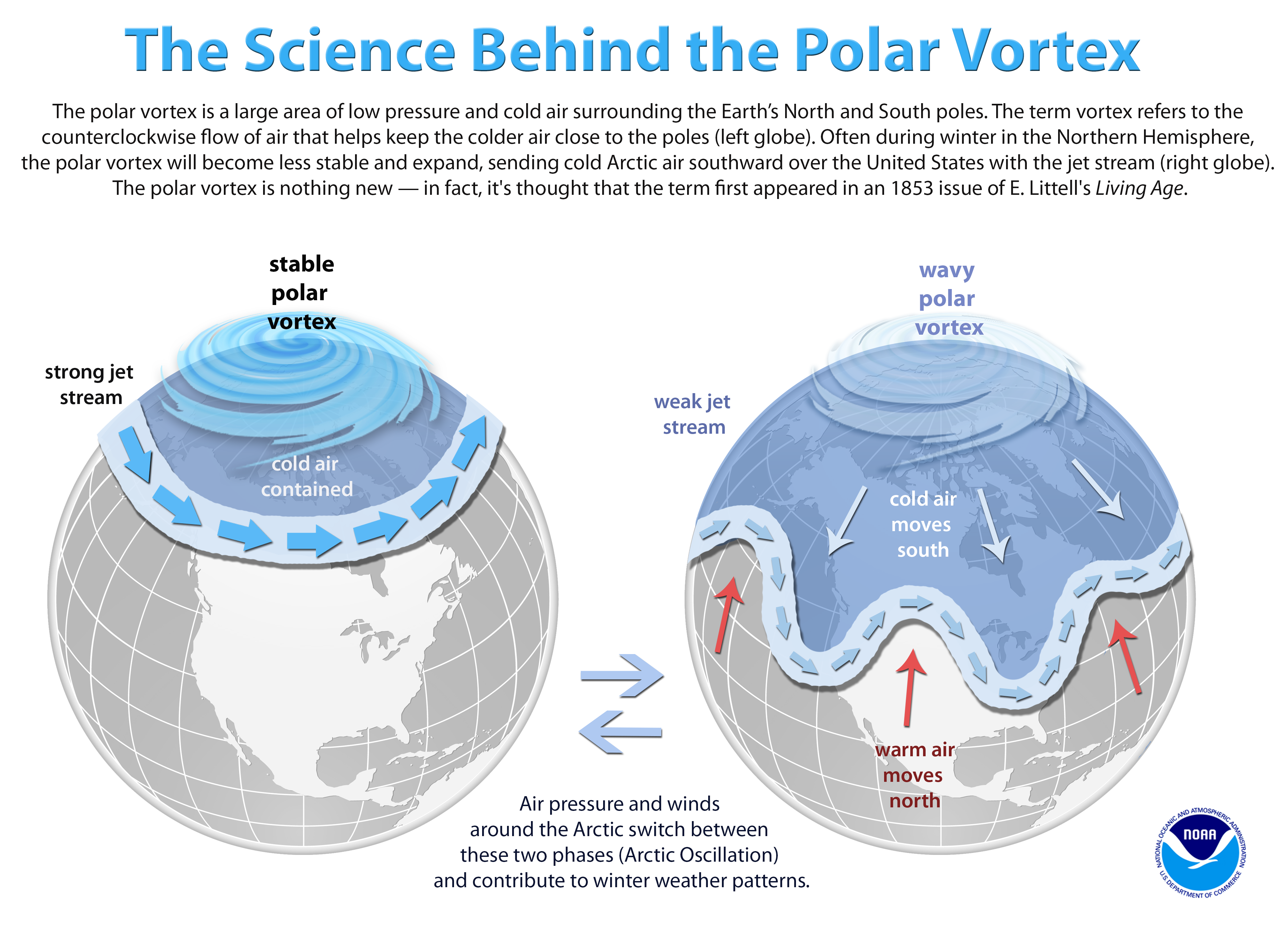

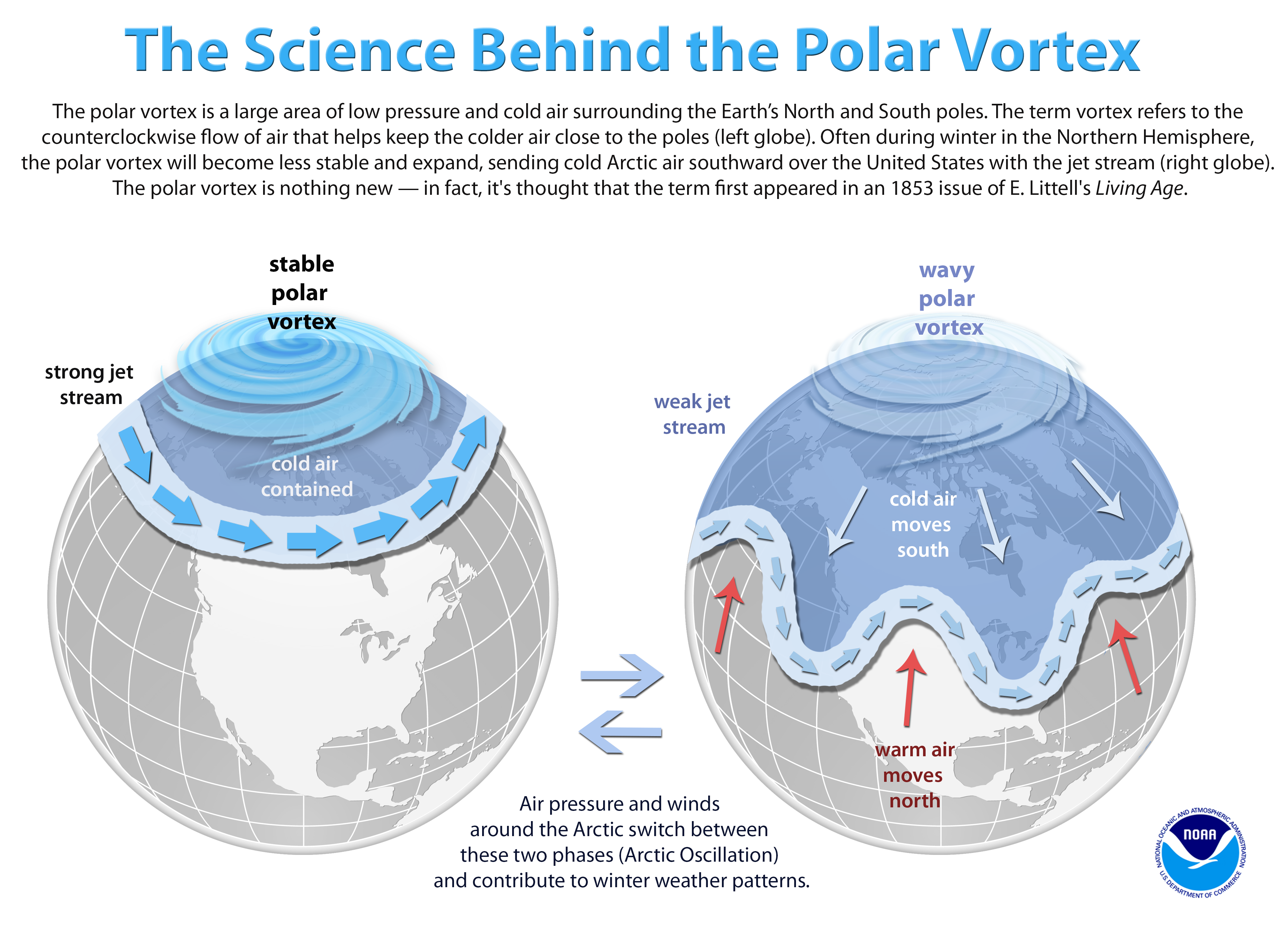

These arctic air events are often brought on by a sudden warming event in the polar stratosphere, the layer of air above the troposphere (the lowest level of the atmosphere in which we all live). These sudden warming events cause the arctic jet stream to loosen, or wobble, instead of maintaining a tighter circulation which traps the cold air around the polar regions. This wobble allows polar air to spill well away from the coldest regions of the Northern Hemisphere.

One of these events occurred in early January, and is still playing a major role in bringing wintry weather to millions of people. Read more about background on the polar vortex here.

This graphic presents the fundamental atmospheric drivers of the polar vortex. New research suggests scientists may one day be able to improve predictability of extreme weather in the mid-latitudes that result from stratospheric events which disrupt the polar vortex. Credit: NOAA

Sudden Stratospheric Warming events are well-known for bringing an increased likelihood of extreme cold to the Eastern United States, as well as Northern Europe and Asia, but the study's results indicate more widespread and longer lasting impacts. Recent flooding in England from a train of storms is an example of a stubborn, slow moving storm system caused by the SSW and its changes to the polar jet.

Currently, these events can typically be predicated with precision a few days in advance, with indications of their potential showing up days prior. In this most recent event, scientists knew there would be perturbations in the polar jet after the SSW lasting for weeks or longer, but could not precisely say when a specific region would be impacted.

With further study and continued improvement in weather modeling, it may be possible to extend the lead time for less specific aspects of these events (such as outbreaks of cold or a persistent dip in the jet stream) weeks in advance, although it's unlikely more specific forecast details (such as snow totals) will be predictable in the same time frame.

This graphic presents the fundamental atmospheric drivers of the polar vortex. New research suggests scientists may one day be able to improve predictability of extreme weather in the mid-latitudes that result from stratospheric events which disrupt the polar vortex. Credit: NOAA

Sudden Stratospheric Warming events are well-known for bringing an increased likelihood of extreme cold to the Eastern United States, as well as Northern Europe and Asia, but the study's results indicate more widespread and longer lasting impacts. Recent flooding in England from a train of storms is an example of a stubborn, slow moving storm system caused by the SSW and its changes to the polar jet.

Currently, these events can typically be predicated with precision a few days in advance, with indications of their potential showing up days prior. In this most recent event, scientists knew there would be perturbations in the polar jet after the SSW lasting for weeks or longer, but could not precisely say when a specific region would be impacted.

With further study and continued improvement in weather modeling, it may be possible to extend the lead time for less specific aspects of these events (such as outbreaks of cold or a persistent dip in the jet stream) weeks in advance, although it's unlikely more specific forecast details (such as snow totals) will be predictable in the same time frame.

This graphic presents the fundamental atmospheric drivers of the polar vortex. New research suggests scientists may one day be able to improve predictability of extreme weather in the mid-latitudes that result from stratospheric events which disrupt the polar vortex. Credit: NOAA

Sudden Stratospheric Warming events are well-known for bringing an increased likelihood of extreme cold to the Eastern United States, as well as Northern Europe and Asia, but the study's results indicate more widespread and longer lasting impacts. Recent flooding in England from a train of storms is an example of a stubborn, slow moving storm system caused by the SSW and its changes to the polar jet.

Currently, these events can typically be predicated with precision a few days in advance, with indications of their potential showing up days prior. In this most recent event, scientists knew there would be perturbations in the polar jet after the SSW lasting for weeks or longer, but could not precisely say when a specific region would be impacted.

With further study and continued improvement in weather modeling, it may be possible to extend the lead time for less specific aspects of these events (such as outbreaks of cold or a persistent dip in the jet stream) weeks in advance, although it's unlikely more specific forecast details (such as snow totals) will be predictable in the same time frame.

This graphic presents the fundamental atmospheric drivers of the polar vortex. New research suggests scientists may one day be able to improve predictability of extreme weather in the mid-latitudes that result from stratospheric events which disrupt the polar vortex. Credit: NOAA

Sudden Stratospheric Warming events are well-known for bringing an increased likelihood of extreme cold to the Eastern United States, as well as Northern Europe and Asia, but the study's results indicate more widespread and longer lasting impacts. Recent flooding in England from a train of storms is an example of a stubborn, slow moving storm system caused by the SSW and its changes to the polar jet.

Currently, these events can typically be predicated with precision a few days in advance, with indications of their potential showing up days prior. In this most recent event, scientists knew there would be perturbations in the polar jet after the SSW lasting for weeks or longer, but could not precisely say when a specific region would be impacted.

With further study and continued improvement in weather modeling, it may be possible to extend the lead time for less specific aspects of these events (such as outbreaks of cold or a persistent dip in the jet stream) weeks in advance, although it's unlikely more specific forecast details (such as snow totals) will be predictable in the same time frame.All Weather News

More