Wildfire Temperatures Key To Understanding Smoke Impacts

Wildfire Temperatures Key To Understanding Smoke Impacts From NOAA

New NOAA-led research has found that the temperature of a wildfire is a better predictor of what’s in the smoke than the type of fuel being burned - a surprising result that will advance a wildfire smoke-modeling tool currently under development.

Researchers found that around 85 percent of the variability of volatile organic compound emissions was controlled by the burn temperature, and that the lower the temperature, the more toxic the smoke. The scientific results come from a 2016 experiment involving closely monitored controlled burns inside the University of Montana’s Fire Lab. The findings were recently published in the journal Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics.

“If we know the temperature of a fire, we can better estimate what comes out of it, independent of what’s burning,” said co-author Carsten Warneke, a CIRES scientist working in the NOAA Earth System Research Laboratory. “With that information, we’ll be able to simplify the emissions models, better predict the downwind impacts of wildfires, and get much better forecasts for air quality.”

[A heavy-lift helicopter makes a water drop on a hot spot during the Waldo Canyon fire, which swept into Colorado Springs in June, 2012. The wildfire destroyed 346 homes, making it Colorado's most destructive at the time.Photo credit: U.S. Air Force photo/Master Sgt. Jeremy Lock]

Volatile organic compounds, or VOCs, are one component of emissions produced by the complex chemistry of a wildfire. Particulates, including soot and tiny particles known as PM 2.5 are another. Scientists had assumed wildfire emissions were mostly dependent on the type of fuel burned— such as trees, shrubs, grass or forest duff.

FINDINGS WERE A REVELATION

To investigate, a team of CIRES and NOAA scientists ignited over 100 fires from various fuels found in the western United States and sampled the emissions continuously with state-of-the art instruments.

“These results completely change the way we understand VOC emissions from wildfires,” said NOAA scientist James Roberts, a team member. “Instead of looking at the type of fuel burned, we can focus on the temperature of the burn, something that can potentially be measured from satellites.”

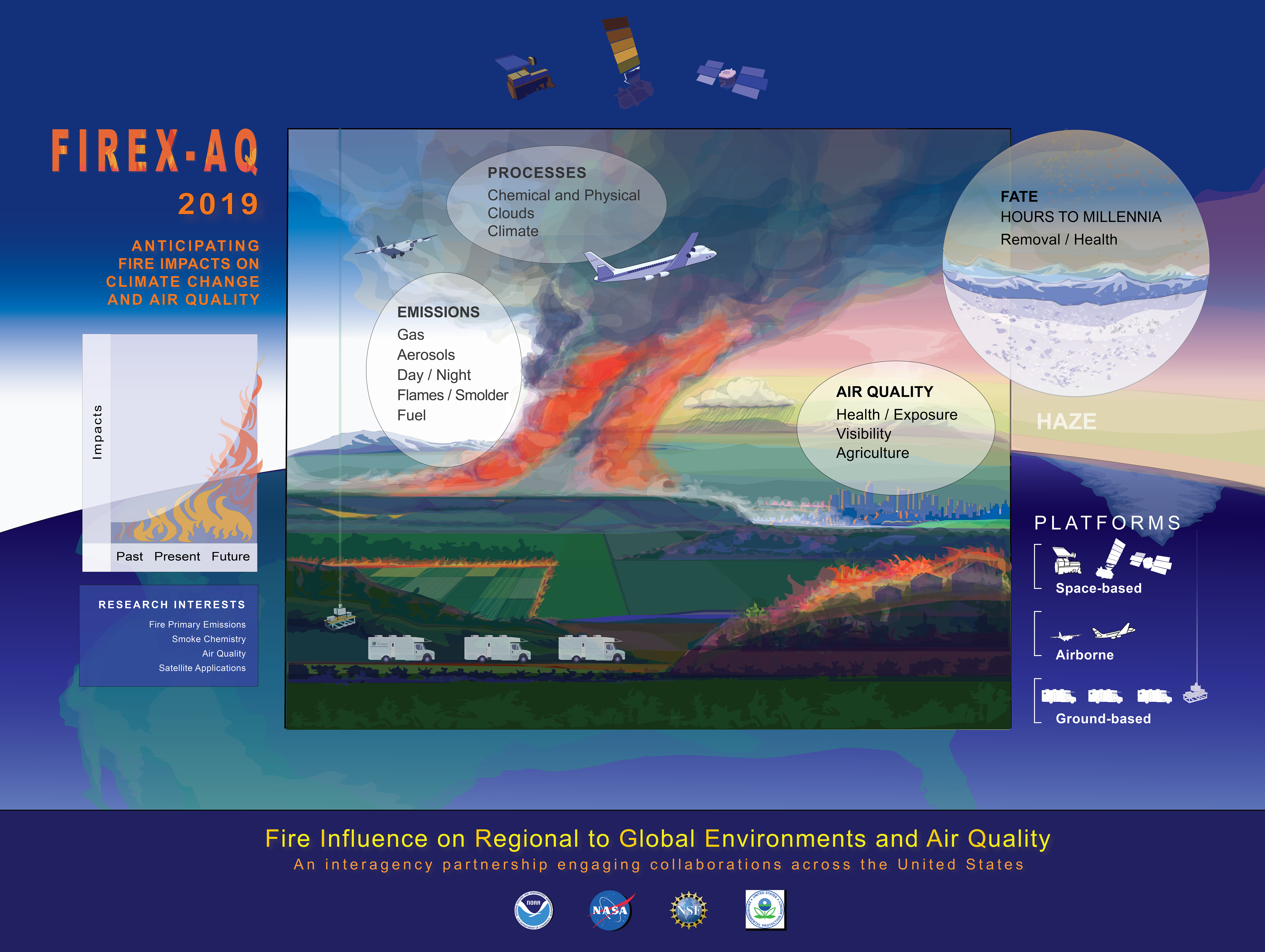

[In 2019, NOAA and NASA will join forces with several other scientific institutions for a comprehensive field campaign to study the impact of wildfire smoke on regional and global air quality. Dubbed FIREX-AQ, the mission will investigate the chemistry of wildfire smoke at the source and as it moves downwind, with a goal of making satellite observations more useful to forecasters. Credit: CIRES/NOAA]

Warneke said the ultimate goal of this research is to produce a unified smoke composition and transport model that will help public health managers predict and prepare for health impacts. Wildfire emissions can be transported over long distances, spreading toxic constituents and contributing to the formation of secondary pollutants such as ozone and fine particulates, or PM 2.5, hundreds of miles from the fire source. He noted that NOAA’s experimental High Resolution Rapid Refresh smoke model, which is currently being used by forecasters in California, predicts the movement of fine particulates, but not other important smoke constituents.“PM 2.5 is the most important indicator, but not the only one,” Warneke said. “We know fires produce toxic emissions, like benzene. Wildfires are becoming larger and more frequent. We need to know what’s in the smoke.”

RESULTS TO SUPPORT NOAA-NASA RESEARCH CAMPAIGN

Results from the Montana Fire Lab experiment also show that lower-temperature fires produce more PM 2.5, which can get deep into people's lungs and produce a variety of health impacts.

These initial Fire Lab results will help inform the design of a 2019 field campaign to be led by NOAA and NASA called FIREX-AQ, short for Fire Influence on Regional to Global Environments Experiment–and Air Quality. The team will deploy NASA’s DC-8 flying chemistry lab, along with other airplanes, instrumented vans and satellites to study the impact of western U.S. wildfires on the atmosphere and climate with the goal of developing better information and tools to help manage fires.

“By doing our homework in the lab, we have identified what’s in emissions and the actual process of how emissions are made,” said Warneke. “Now we need to go into the field to understand real fires.”

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace Michaels