Studying Wind Behavior and Terrain to Improve Wind Forecasts

[Windmills along the Columbia River Gorge. From NOAA]

[NOAA] New research on wind behavior in complex terrain, led by NOAA and the U.S. Department of Energy, will improve wind forecasts for the entire country. Forecasts for wind energy firms may improve by 15-25 percent, according to the study.

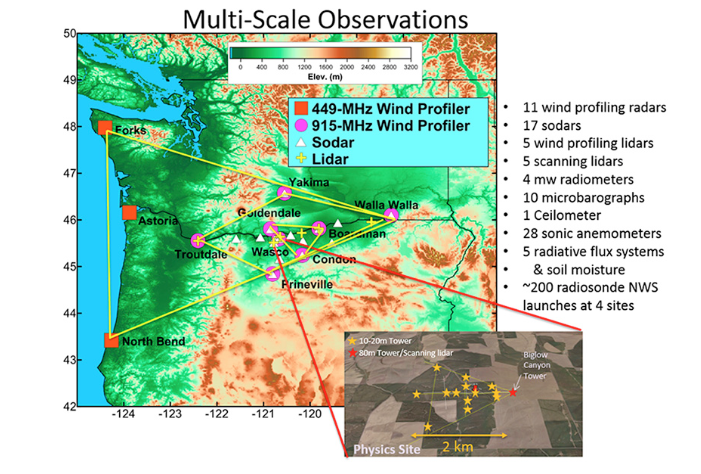

The Wind Forecast Improvement Project 2, or WFIP2, focused on improving NOAA’s short-term weather forecasts of wind speeds in areas such as mountains, canyons, and coastlines, landforms often associated with abundant wind energy potential. The project was based in the windswept Columbia River Gorge in Washington and Oregon, where wind farms can generate as much power as five 800-megawatt nuclear power plants. Researchers collected 18 months of data to better understand how terrain and weather physics affect forecasts of wind speed and turbulence at the height of wind turbines, data that researchers then used to improve the High Resolution Rapid Refresh (HRRR) short-term weather model’s representation of low-level winds. The scope of the project was unprecedented, with more than 200 instruments deployed across 50,000 square kilometers. [Map showing the WFIP2 region of study and the arrangement of select instruments.]

“This is a comprehensive investigation of winds in complex terrain,” said Dave Turner, manager of the NOAA Global Systems Division’s Atmospheric Science for Renewable Energy Program. “It gives us a unique opportunity to evaluate how well the HRRR represents weather in challenging conditions, and has already led to improvements in our ability to forecast low-level winds. And we’re just scratching the surface - additional work will certainly lead to further forecast improvements.”

[Map showing the WFIP2 region of study and the arrangement of select instruments.]

“This is a comprehensive investigation of winds in complex terrain,” said Dave Turner, manager of the NOAA Global Systems Division’s Atmospheric Science for Renewable Energy Program. “It gives us a unique opportunity to evaluate how well the HRRR represents weather in challenging conditions, and has already led to improvements in our ability to forecast low-level winds. And we’re just scratching the surface - additional work will certainly lead to further forecast improvements.”

The Columbia River Gorge is a deep canyon carved by the Columbia River stretching for more than 80 miles from high desert through the Cascade Range. The dramatic topography of the gorge creates highly variable wind conditions - weather fronts, mountain waves, topographic wakes, thunderstorm outflows, cold pools and marine pushes - either triggered or amplified by the terrain, which impact how much electricity wind turbines can generate.

Once the field project ended in 2017, the researchers produced a comprehensive dataset of meteorological processes that allowed NOAA modelers to solve a problem that had long vexed grid operators: more accurate predictions of the transition between cold, stable air to windy conditions, transitions that often result in a surge of power generated by wind turbines. Previously, weather models have been too aggressive in their predictions, resulting in over-estimates of power surges and false alarms for wind ramp-ups.

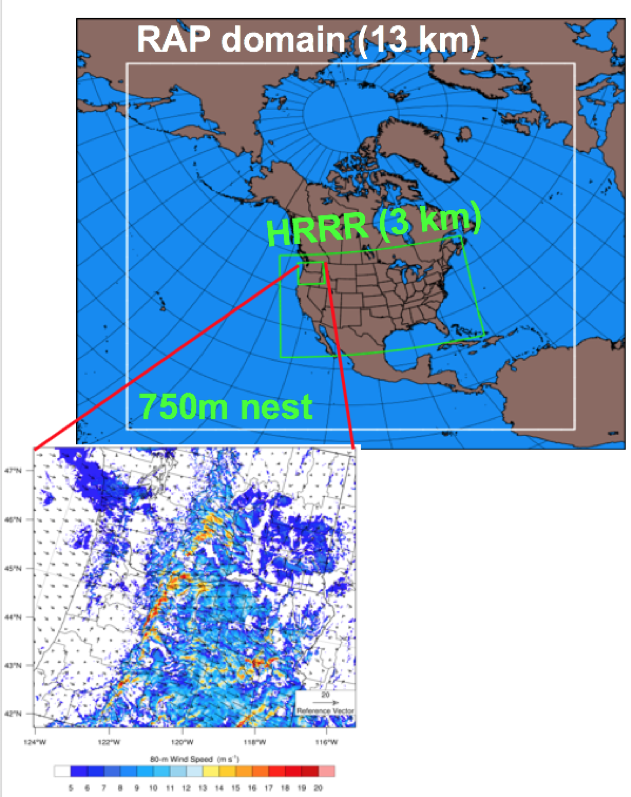

Data collected during WFIP 2 allowed a NOAA modeling team to improve wind forecasts by 15-25 percent depending on weather conditions, with the best results in the winter when cold pools are more common. [Image of 750 meter HRRR “nest” over the WFIP2 project region. Credit: NOAA]

The models used for the project were the 13 km grid Rapid Refresh (RAP) model, the 3 km grid High-Resolution Rapid Refresh (HRRR) model, and a 0.75 km nest within the HRRR that provide high-resolution forecasts.

“The improvements to NOAA’s HRRR model made by WFIP2 are helping Vaisala to better forecast energy output for wind projects both before and after they are built,” said Pascal Storck, director of renewable energy for Vaisala, Inc. “The focus on a publicly available model means that these benefits are reaching the entire industry.“

[Image of 750 meter HRRR “nest” over the WFIP2 project region. Credit: NOAA]

The models used for the project were the 13 km grid Rapid Refresh (RAP) model, the 3 km grid High-Resolution Rapid Refresh (HRRR) model, and a 0.75 km nest within the HRRR that provide high-resolution forecasts.

“The improvements to NOAA’s HRRR model made by WFIP2 are helping Vaisala to better forecast energy output for wind projects both before and after they are built,” said Pascal Storck, director of renewable energy for Vaisala, Inc. “The focus on a publicly available model means that these benefits are reaching the entire industry.“

Researchers demonstrated that the updated HRRR, which incorporated changes resulting from the WFIP2 analysis, also improved wind forecasts in other regions across the United States. This new version of HRRR became operational at NOAA’s National Center for Environmental Prediction in July 2018.

“WFIP2 is an excellent example of a successful end-to-end research program,” said Jim Wilczak, a senior scientist on the NOAA Physical Sciences Division Boundary Layer Observations and Processes Team. “We collected observations, used them to better understand the meteorological processes affecting the local weather, and then used that to improve our weather prediction models - and forecast skill.” Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace Michaels