Great Lakes Ice, Evaporation, and Water Levels

Special Stories

15 Jan 2020 2:00 AM

[On March 6, 2014, Great Lakes ice cover was 92.5%, putting winter 2014 into 2nd place in the record books for maximum ice cover. Satellite photo credit: NOAA Great Lakes CoastWatch and NASA.]

[NOAA by Gabrielle Farina] As many of us in the Great Lakes community start to don our parkas and break out the snow shovels again, we know the splashing waves on our shorelines will soon be replaced with ice. And, with near-record high water levels in the lakes this year, the question of how ice and water levels will affect coastal communities in the months ahead looms large.

Based on this experimental model’s results, NOAA GLERL projects this Great Lakes ice cover this winter to be around 47%. That’s almost 9% below the long-term average of 55.7%. Here’s the preliminary projection broken down by lake:

Lake Superior: 54%

Lake Michigan: 41%

Lake Huron: 66%

Lake Erie: 80%

Lake Ontario: 32%

Based on this experimental model’s results, NOAA GLERL projects this Great Lakes ice cover this winter to be around 47%. That’s almost 9% below the long-term average of 55.7%. Here’s the preliminary projection broken down by lake:

Lake Superior: 54%

Lake Michigan: 41%

Lake Huron: 66%

Lake Erie: 80%

Lake Ontario: 32%

[Ice conditions in Lake Superior under a clear blue sky near Grand Marais. March 24, 2014. Credit: NOAA]

[Ice conditions in Lake Superior under a clear blue sky near Grand Marais. March 24, 2014. Credit: NOAA]

The role of ice in the Great Lakes water budget

To start, we know that evaporation plays a major role in water levels by withdrawing water that enters the lakes from precipitation and runoff. So, high evaporation contributes to lower water levels, and low evaporation contributes to higher water levels. (For more on the Great Lakes water budget, check out this infographic.) Traditional thinking is that high ice cover forms a “cap” that leads to decreased evaporation of lake water. However, we now know that the relationship between ice, evaporation, and water levels is more complex than that. While this assessment on Great Lakes evaporation from Great Lakes Integrated Sciences & Assessments explains that high ice cover is still associated with less evaporation the following spring, it also reports that evaporation rates before winter have an effect on how much ice forms in the first place. Specifically, it explains that high evaporation rates in the fall correspond with high ice cover the following winter. So just as ice cover can influence evaporation, the reverse is true as well – a much different story than the one-way street it was previously thought to be.

A look at 2020 ice cover: NOAA GLERL’s observations & predictions

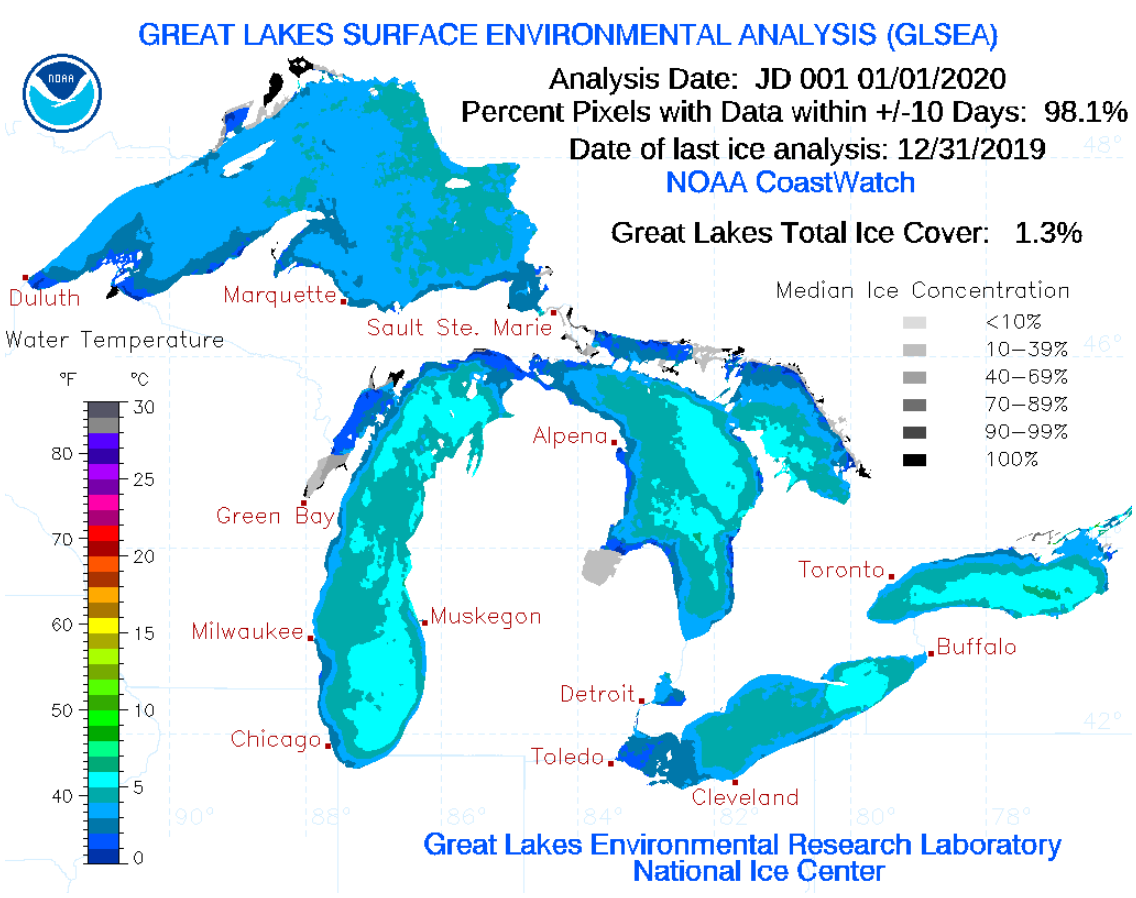

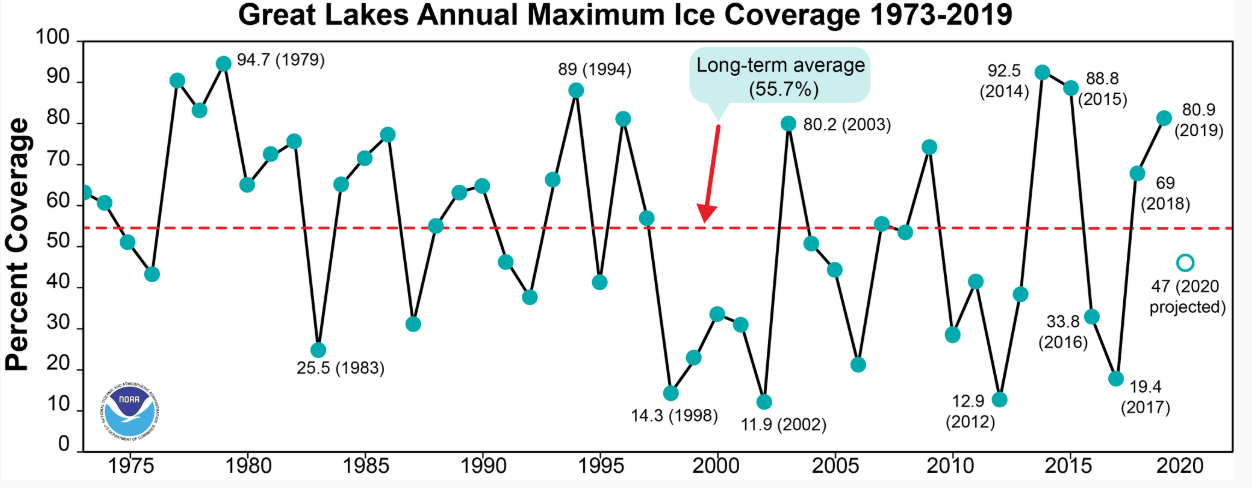

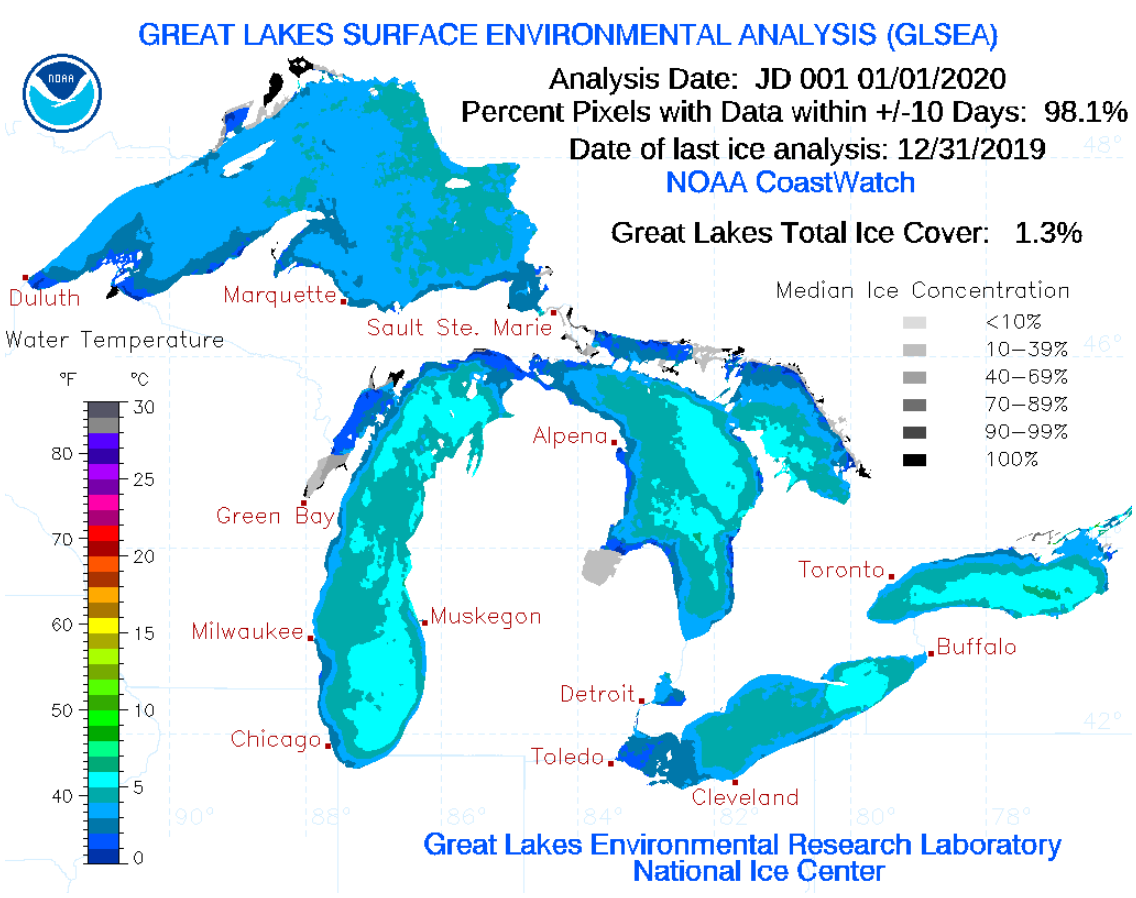

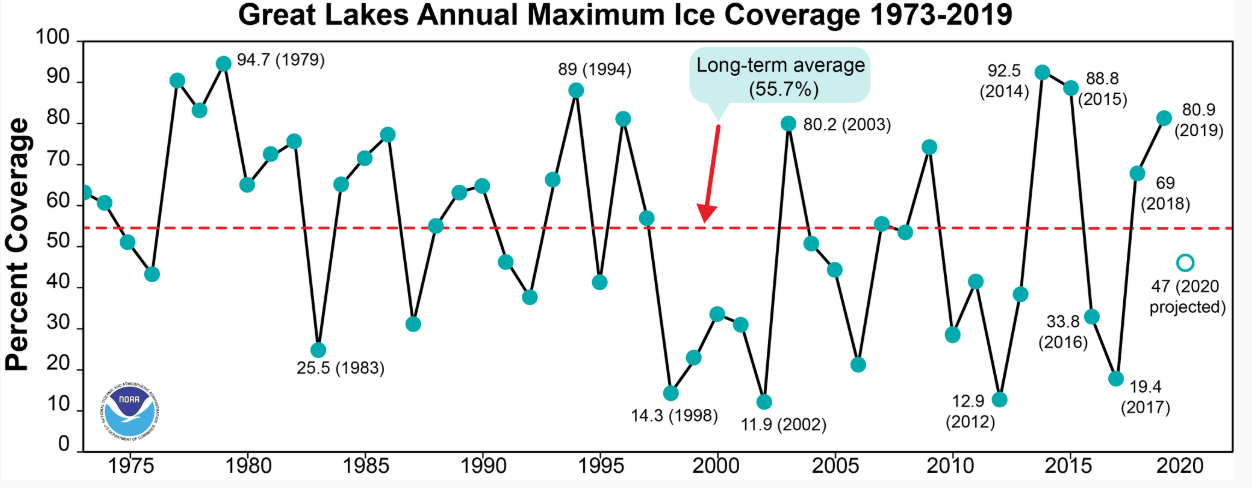

On January 1st, 2020, the total Great Lakes ice cover was 1.3%. That’s about a third as much ice as around the same time last year, and barely anything compared to early 2018, when it was already about 20%. You’ll see in the figure below that shallow, protected bays tend to freeze first, especially ones that are located in the northern Great Lakes region. So it makes sense that most of the ice so far is in the bays of Lake Superior, followed by northern bays in Lakes Michigan and Huron like Green Bay and Georgian Bay. GLERL conducts research on ice cover forecasting on two different time scales: short-term (1-5 days) and seasonal. GLERL’s short-term ice forecasting is part of the upgrade to the Great Lakes Operational Forecast System (GLOFS), a set of models currently being transitioned to operations at the National Ocean Service to predict things like currents, water temperature, water levels, and ice. The ice nowcast and forecast products (concentration, thickness, velocity) have been tested for the past several years and will soon become operational (available for the general public). GLERL’s ice climatologist, Jia Wang, produces an experimental annual projection for Great Lakes ice cover using a statistical model that predicts maximum Great Lakes ice cover percentages for the entire season. This model’s prediction is based on the predicted behaviors of four global-scale air masses: ENSO (El Nino and Southern Oscillation), NAO (North Atlantic Oscillation), PDO (Pacific Decadal Oscillation), and AMO (Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation). While they’re all pretty far away from the Great Lakes, past research has shown that these air masses — or global teleconnections — heavily influence the year-to-year variability of Great Lakes ice cover. Based on this experimental model’s results, NOAA GLERL projects this Great Lakes ice cover this winter to be around 47%. That’s almost 9% below the long-term average of 55.7%. Here’s the preliminary projection broken down by lake:

Lake Superior: 54%

Lake Michigan: 41%

Lake Huron: 66%

Lake Erie: 80%

Lake Ontario: 32%

Based on this experimental model’s results, NOAA GLERL projects this Great Lakes ice cover this winter to be around 47%. That’s almost 9% below the long-term average of 55.7%. Here’s the preliminary projection broken down by lake:

Lake Superior: 54%

Lake Michigan: 41%

Lake Huron: 66%

Lake Erie: 80%

Lake Ontario: 32%

Predicting Great Lakes water levels

Forecasts of Great Lakes monthly-average water levels are based on computer models, including some from NOAA GLERL, along with more than 150 years of data from past weather and water level conditions. The official 6-month forecast is produced each month through a binational partnership between the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and Environment and Climate Change Canada. Want to know more about GLERL’s ice research? Visit the ice cover webpage for current conditions, forecasts, historical data, and more! [Ice conditions in Lake Superior under a clear blue sky near Grand Marais. March 24, 2014. Credit: NOAA]

[Ice conditions in Lake Superior under a clear blue sky near Grand Marais. March 24, 2014. Credit: NOAA]

Great Lakes ice cover facts since 1973

94.7% ice coverage in 1979 is the maximum on record. 9.5% ice coverage in 2002 is the lowest on record. 11.5% ice coverage in 1998, a strong El Niño year. The extreme ice cover in 2014 (92.5%) and 2015 (88.8%) were the first consecutive high ice cover years since the late 1970’s.All Weather News

More